Ludwig Wittgenstein

Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway

This digital edition is based on Ludwig Wittgenstein. "Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway." Notebooks 1914–1916, edited by G. H. von Wright and G. E. M. Anscombe, Harper & Row, 1969, pp. 107–118. This original-language text is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 70 years or fewer.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway

Logical so-called propositions shew [the] logical properties of language and therefore of [the] Universe, but say nothing.

This means that by merely looking at them you can see these proper ties; whereas, in a proposition proper, you cannot see what is true by looking at it.

It is impossible to say what these properties are, because in order to do so, you would need a language, which hadn't got the properties in question, and it is impossible that this should be a proper language. Impossible to construct [an] illogical language.

In order that you should have a language which can express or say everything that can be said, this language must have certain properties; and when this is the case, that it has them can no longer be said in that language or any language.

An illogical language would be one in which, e.g., you could put an event into a hole.

Thus a language which can express everything mirrors certain properties of the world by these properties which it must have; and logical so-called propositions shew in a systematic way those properties.

How, usually, logical propositions do shew these properties is this: We give a certain description of a kind of symbol; we find that other symbols, combined in certain ways, yield a symbol of this description; and that they do shews something about these symbols.

As a rule the description [given] in ordinary Logic is the description of a tautology; but others might shew equally well, e.g., a contradiction.

Every real proposition shews something, besides what it says, about the Universe: for, if it has no sense, it can't be used; and if it has a sense, it mirrors some logical property of the Universe.

E.g., take ϕa, ϕa ⊃ ψa, ψa. By merely looking at these three, I can see that 3 follows from 1 and 2; i.e. I can see what is called the truth of a logical proposition, namely, of [the] proposition ϕa . ϕa ⊃ ψa : ⊃ : ψa. But this is not a proposition; but by seeing that it is a tautology I can see what I already saw by looking at the three propositions: the difference is that I now see that it is a tautology.

We want to say, in order to understand [the] above, what properties a symbol must have, in order to be a tautology.

Many ways of saying this are possible:

One way is to give certain symbols; then to give a set of rules for combining them; and then to say: any symbol formed from those symbols, by combining them according to one of the given rules, is a tautology. This obviously says something about the kind of symbol you can get in this way.

This is the actual procedure of [the] old Logic: it gives so-called primitive propositions; so-called rules of deduction; and then says that what you get by applying the rules to the propositions is a logical proposition that you have proved. The truth is, it tells you something about the kind of propositions you have got, viz. that it can be derived from the first symbols by these rules of combination (= is a tautology).

Therefore, if we say one logical proposition follows logically from another, this means something quite different from saying that a real proposition follows logically from another. For so-called proof of a logical proposition does not prove its truth (logical propositions are neither true nor false) but proves that it is a logical proposition (= is a tautology).

Logical propositions are forms of proof: they shew that one or more propositions follow from one (or more).

Logical propositions shew something, because the language in which they are expressed can say everything that can be said.

This same distinction between what can be shewn by the language but not said, explains the difficulty that is felt about types—e.g., as to [the] difference between things, facts, properties, relations. That M is a thing can't be said; it is nonsense: but something is shewn by the symbol "M". In [the] same way, that a proposition is a subject-predicate proposition can't be said: but it is shown by the symbol.

Therefore a theory of types is impossible. It tries to say something about the types, when you can only talk about the symbols. But what you say about the symbols is not that this symbol has that type, which would be nonsense for [the] same reason: but you say simply: This is the symbol, to prevent a misunderstanding. E.g., in "aRb", "R" is not a symbol, but that "R" is between one name and another symbolizes. Here we have not said: this symbol is not of this type but of that, but only: This symbolizes and not that. This seems again to make the same mistake, because "symbolizes" is "typically ambiguous". The true analysis is: "R" is no proper name, and, that "R" stands between "a" and "b" expresses a relation. Here are two propositions of different type connected by "and".

It is obvious that, e.g., with a subject-predicate proposition, if it has any sense at all, you see the form, so soon as you understand the proposition, in spite of not knowing whether it is true or false. Even if there were propositions of [the] form "M is a thing" they would be superfluous (tautologous) because what this tries to say is something which is already seen when you see "M".

In the above expression "aRb", we were talking only of this particular "R", whereas what we want to do is to talk of all similar symbols. We have to say: in any symbol of this form what corresponds to "R" is not a proper name, and the fact that ["R" stands between "a" and "b"] expresses a relation. This is what is sought to be expressed by the nonsensical assertion: Symbols like this are of a certain type. This you can't say, because in order to say it you must first know what the symbol is: and in knowing this you see [the] type and therefore also [the] type of [what is] symbolized. I.e. in knowing what symbolizes, you know all that is to be known; you can't say anything about the symbol.

For instance: Consider the two propositions (1) "What symbolizes here is a thing", (2) "What symbolizes here is a relational fact (= relation)". These are nonsensical for two reasons: (a) because they mention "thing" and "relation"; (b) because they mention them in propositions of the same form. The two propositions must be expressed in entirely different forms, if properly analysed; and neither the word "thing" nor "relation" must occur.

Now we shall see how properly to analyse propositions in which "thing", "relation", etc., occur.

(1) Take ϕx. We want to explain the meaning of 'In "ϕx" a thing symbolizes'. The analysis is:—

(∃y) . y symbolizes . y = "x" . "ϕx"

["x" is the name of y: "ϕx" = '"ϕ" is at [the] left of "x"' and says ϕx.]

N.B. "x" can't be the name of this actual scratch y, because this isn't a thing: but it can be the name of a thing; and we must understand that what we are doing is to explain what would be meant by saying of an ideal symbol, which did actually consist in one thing's being to the left of another, that in it a thing symbolized.

(N.B. In [the] expression (∃y) . ϕy, one is apt to say this means "There is a thing such that...". But in fact we should say "There is a y, such that..."; the fact that the y symbolizes expressing what we mean.)

In general: When such propositions are analysed, while the words "thing", "fact", etc. will disappear, there will appear instead of them a new symbol, of the same form as the one of which we are speaking; and hence it will be at once obvious that we cannot get the one kind of proposition from the other by substitution.

In our language names are not things: we don't know what they are: all we know is that they are of a different type from relations, etc. etc. The type of a symbol of a relation is partly fixed by [the] type of [a] symbol of [a] thing, since a symbol of [the] latter type must occur in it.

N.B. In any ordinary proposition, e.g., "Moore good", this shews and does not say that "Moore" is to the left of "good"; and here what is shewn can be said by another proposition. But this only applies to that part of what is shewn which is arbitrary. The logical properties which it shews are not arbitrary, and that it has these cannot be said in any proposition.

When we say of a proposition of [the] form "aRb" that what symbolizes is that "R" is between "a" and "b", it must be remembered that in fact the proposition is capable of further analysis because a, R, and b are not simples. But what seems certain is that when we have analysed it we shall in the end come to propositions of the same form in respect of the fact that they do consist in one thing being between two others.

How can we talk of the general form of a proposition, without knowing any unanalysable propositions in which particular names and relations occur? What justifies us in doing this is that though we don't know any unanalysable propositions of this kind, yet we can understand what is meant by a proposition of the form (∃x, y, R) . xRy (which is unanalysable), even though we know no proposition of the form xRy.

If you had any unanalysable proposition in which particular names and relations occurred (and unanalysable proposition = one in which only fundamental symbols = ones not capable of definition, occur) then you can always form from it a proposition of the form (∃x, y, R) . xRy, which though it contains no particular names and relations, is unanalysable.

(2) The point can here be brought out as follows. Take ϕa and ϕA: and ask what is meant by saying, "There is a thing in ϕa, and a complex in ϕA"?

(1) means: (∃x) . ϕx . x = a

(2) means: (∃x, ψξ) . ϕA = ψx . ϕx.

Use of logical propositions. You may have one so complicated that you cannot, by looking at it, see that it is a tautology; but you have shewn that it can be derived by certain operations from certain other propositions according to our rule for constructing tautologies; and hence you are enabled to see that one thing follows from another, when you would not have been able to see it otherwise. E.g., if our tautology is of [the] form p ⊃ q you can see that q follows from p; and so on.

The Bedeutung of a proposition is the fact that corresponds to it, e.g., if our proposition be "aRb", if it's true, the corresponding fact would be the fact aRb, if false, the fact ~aRb. But both "the fact aRb" and "the fact ~aRb" are incomplete symbols, which must be analysed.

That a proposition has a relation (in wide sense) to Reality, other than that of Bedeutung, is shewn by the fact that you can understand it when you don't know the Bedeutung, i.e. don't know whether it is true or false. Let us express this by saying "It has sense" (Sinn).

In analysing Bedeutung, you come upon Sinn as follows:

We want to explain the relation of propositions to reality.

The relation is as follows: Its simples have meaning = are names of simples; and its relations have a quite different relation to relations; and these two facts already establish a sort of correspondence between a proposition which contains these and only these, and reality: i.e. if all the simples of a proposition are known, we already know that we can describe reality by saying that it behaves in a certain way to the whole proposition. (This amounts to saying that we can compare reality with the proposition. In the case of two lines we can compare them in respect of their length without any convention: the comparison is automatic. But in our case the possibility of comparison depends upon the conventions by which we have given meanings to our simples (names and relations).)

It only remains to fix the method of comparison by saying what about our simples is to say what about reality. E.g., suppose we take two lines of unequal length: and say that the fact that the shorter is of the length it is is to mean that the longer is of the length it is. We should then have established a convention as to the meaning of the shorter, of the sort we are now to give.

From this it results that "true" and "false" are not accidental properties of a proposition, such that, when it has meaning, we can say it is also true or false: on the contrary, to have meaning means to be true or false: the being true or false actually constitutes the relation of the proposition to reality, which we mean by saying that it has meaning (Sinn).

There seems at first sight to be a certain ambiguity in what is meant by saying that a proposition is "true", owing to the fact that it seems as if, in the case of different propositions, the way in which they correspond to the facts to which they correspond is quite different. But what is really common to all cases is that they must have the general form of a proposition. In giving the general form of a proposition you are explaining what kind of ways of putting together the symbols of things and relations will correspond to (be analogous to) the things having those relations in reality. In doing thus you are saying what is meant by saying that a proposition is true; and you must do it once for all. To say "This proposition has sense" means '"This proposition is true" means ... .' ("p" is true = "p" . p. Def. : only instead of "p" we must here introduce the general form of a proposition.)

It seems at first sight as if the ab notation must be wrong, because it seems to treat true and false as on exactly the same level. It must be possible to see from the symbols themselves that there is some essential difference between the poles, if the notation is to be right; and it seems as if in fact this was impossible.

The interpretation of a symbolism must not depend upon giving a different interpretation to symbols of the same types.

How asymmetry is introduced is by giving a description of a particular form of symbol which we call a "tautology". The description of the ab-symbol alone is symmetrical with respect to a and b; but this description plus the fact that what satisfies the description of a tautology is a tautology is asymmetrical with regard to them. (To say that a description was symmetrical with regard to two symbols, would mean that we could substitute one for the other, and yet the description remain the same, i.e. mean the same.)

Take p.q and q. When you write p.q in the ab notation, it is impossible to see from the symbol alone that q follows from it, for if you were to interpret the true-pole as the false, the same symbol would stand for p ∨ q, from which q doesn't follow. But the moment you say which symbols are tautologies, it at once becomes possible to see from the fact that they are and the original symbol that q does follow.

Logical propositions, of course, all shew something different: all of them shew, in the same way, viz. by the fact that they are tautologies, but they are different tautologies and therefore shew each something different.

What is unarbitrary about our symbols is not them, nor the rules we give; but the fact that, having given certain rules, others are fixed = follow logically.

Thus, though it would be possible to interpret the form which we take as the form of a tautology as that of a contradiction and vice versa, they are different in logical form because though the apparent form of the symbols is the same, what symbolizes in them is different, and hence what follows about the symbols from the one interpretation will be different from what follows from the other. But the difference between a and b is not one of logical form, so that nothing will follow from this difference alone as to the interpretation of other symbols. Thus, e.g., p.q, p ∨ q seem symbols of exactly the same logical form in the ab notation. Yet they say something entirely different; and, if you ask why, the answer seems to be: In the one case the scratch at the top has the shape b, in the other the shape a. Whereas the interpretation of a tautology as a tautology is an interpretation of a logical form, not the giving of a meaning to a scratch of a particular shape. The important thing is that the interpretation of the form of the symbolism must be fixed by giving an interpretation to its logical properties, not by giving interpretations to particular scratches.

Logical constants can't be made into variables: because in them what symbolizes is not the same; all symbols for which a variable can be substituted symbolize in the same way.

We describe a symbol, and say arbitrarily "A symbol of this description is a tautology". And then, it follows at once, both that any other symbol which answers to the same description is a tautology, and that any symbol which does not isn't. That is, we have arbitrarily fixed that any symbol of that description is to be a tautology; and this being fixed it is no longer arbitrary with regard to any other symbol whether it is a tautology or not.

Having thus fixed what is a tautology and what is not, we can then, having fixed arbitrarily again that the relation a-b is transitive get from the two facts together that "p ≡ ~(~p)" is a tautology. For ~(~p) = a-b-a-p-b-a-b. The point is: that the process of reasoning by which we arrive at the result that a-b-a-p-b-a-b is the same symbol as a-p-b, is exactly the same as that by which we discover that its meaning is the same, viz. where we reason if b-a-p-b-a, then not a-p-b, if a-b-a-p-b-a-b then not b-a-p-b-a, therefore if a-b-a-p-b-a-b, then a-p-b.

It follows from the fact that a-b is transitive, that where we have a-b-a the first a has to the second the same relation that it has to b. It is just as from the fact that a-true implies b-false, and b-false implies c-true, we get that a-true implies c-true. And we shall be able to see, having fixed the description of a tautology, that p ≡ ~(~p) is a tautology.

That, when a certain rule is given, a symbol is tautological shews a logical truth.

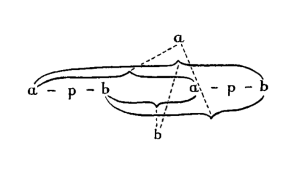

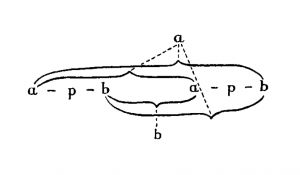

This symbol might be interpreted either as a tautology or a contradiction.[1]

In settling that it is to be interpreted as a tautology and not as a contradiction, I am not assigning a meaning to a and b; i.e. saying that they symbolize different things but in the same way. What I am doing is to say that the way in which the a-pole is connected with the whole symbol symbolizes in a different way from that in which it would symbolize if the symbol were interpreted as a contradiction. And I add the scratches a and b merely in order to shew in which ways the connexion is symbolizing, so that it may be evident that wherever the same scratch occurs in the corresponding place in another symbol, there also the connexion is symbolizing in the same way.

We could, of course, symbolize any ab-function without using two outside poles at all, merely, e.g., omitting the b-pole; and here what would symbolize would be that the three pairs of inside poles of the propositions were connected in a certain way with the a-pole, while the other pair was not connected with it. And thus the difference between the scratches a and b, where we do use them, merely shews that it is a different state of things that is symbolizing in the one case and the other: in the one case that certain inside poles are connected in a certain way with an outside pole, in the other that they are not.

The symbol for a tautology, in whatever form we put it, e.g., whether by omitting the a-pole or by omitting the b, would always be capable of being used as the symbol for a contradiction; only not in the same language.

The reason why ~x is meaningless, is simply that we have given no meaning to the symbol ~ξ. I.e. whereas ϕx and ϕp look as if they were of the same type, they are not so because in order to give a meaning to ~x you would have to have some property ~ξ. What symbolizes in ϕξ is that ϕ stands to the left of a proper name and obviously this is not so in ~p. What is common to all propositions in which the name of a property (to speak loosely) occurs is that this name stands to the left of a name-form.

The reason why, e.g., it seems as if "Plato Socrates" might have a meaning, while "Abracadabra Socrates" will never be suspected to have one, is because we know that "Plato" has one, and do not observe that in order that the whole phrase should have one, what is necessary is not that "Plato" should have one, but that the fact that "Plato" is to the left of a name should.

The reason why "The property of not being green is not green" is nonsense, is because we have only given meaning to the fact that "green" stands to the right of a name; and "the property of not being green" is obviously not that.

ϕ cannot possibly stand to the left of (or in any other relation to) the symbol of a property. For the symbol of a property, e.g., ψx is that ψ stands to the left of a name form, and another symbol ϕ cannot possibly stand to the left of such a fact: if it could, we should have an illogical language, which is impossible.

p is false = ~(p is true) Def.

It is very important that the apparent logical relations ∨, ⊃, etc. need brackets, dots, etc., i.e. have "ranges"; which by itself shews they are not relations. This fact has been overlooked, because it is so universal—the very thing which makes it so important.

There are internal relations between one proposition and another; but a proposition cannot have to another the internal relation which a name has to the proposition of which it is a constituent, and which ought to be meant by saying it "occurs" in it. In this sense one proposition can't "occur" in another.

Internal relations are relations between types, which can't be expressed in propositions, but are all shewn in the symbols themselves, and can be exhibited systematically in tautologies. Why we come to call them "relations" is because logical propositions have an analogous relation to them, to that which properly relational propositions have to relations.

Propositions can have many different internal relations to one another. The one which entitles us to deduce one from another is that if, say, they are ϕa and ϕa ⊃ ψa, then ϕa . ϕa ⊃ ψa : ⊃ : ψa is a tautology.

The symbol of identity expresses the internal relation between a function and its argument: i.e. ϕa = (∃x) . ϕx . x = a.

The proposition (∃x) . ϕx . x = a : ≡ : ϕa can be seen to be a tautology, if one expresses the conditions of the truth of (∃x) . ϕx . x = a, successively, e.g., by saying: This is true if so and so; and this again is true if so and so, etc., for (∃x) . ϕx . x = a; and then also for ϕa. To express the matter in this way is itself a cumbrous notation, of which the ab-notation is a neater translation.

What symbolizes in a symbol, is that which is common to all the symbols which could in accordance with the rules of logic = syntactical rules for manipulation of symbols, be substituted for it.

The question whether a proposition has sense (Sinn) can never depend on the truth of another proposition about a constituent of the first. E.g., the question whether (x) x = x has meaning (Sinn) can't depend on the question whether (∃x) x = x is true. It doesn't describe reality at all, and deals therefore solely with symbols; and it says that they must symbolize, but not what they symbolize.

It's obvious that the dots and brackets are symbols, and obvious that they haven't any independent meaning. You must, therefore, in order to introduce so-called "logical constants" properly, introduce the general notion of all possible combinations of them = the general form of a proposition. You thus introduce both ab-functions, identity, and universality (the three fundamental constants) simultaneously.

The variable proposition p ⊃ p is not identical with the variable proposition ~(p . ~p). The corresponding universals would be identical. The variable proposition ~(p . ~p) shews that out of ~(p.q) you get a tautology by substituting ~p for q, whereas the other does not shew this.

It's very important to realize that when you have two different relations (a,b)R, (c,d)S this does not establish a correlation between a and c, and b and d, or a and d, and b and c: there is no correlation whatsoever thus established. Of course, in the case of two pairs of terms united by the same relation, there is a correlation. This shews that the theory which held that a relational fact contained the terms and relations united by a copula (ε2) is untrue; for if this were so there would be a correspondence between the terms of different relations.

The question arises how can one proposition (or function) occur in another proposition? The proposition or function itself can't possibly stand in relation to the other symbols. For this reason we must introduce functions as well as names at once in our general form of a proposition; explaining what is meant, by assigning meaning to the fact that the names stand between the |, and that the function stands on the left of the names.

It is true, in a sense, that logical propositions are "postulates"—something which we "demand"; for we demand a satisfactory notation.

A tautology (not a logical proposition) is not nonsense in the same sense in which, e.g., a proposition in which words which have no meaning occur is nonsense. What happens in it is that all its simple parts have meaning, but it is such that the connexions between these paralyse or destroy one another, so that they are all connected only in some irrelevant manner.

Logical functions all presuppose one another. Just as we can see ~p has no sense, if p has none; so we can also say p has none if ~p has none. The case is quite different with ϕa, and a; since here a has a meaning independently of ϕa, though ϕa presupposes it.

The logical constants seem to be complex-symbols, but on the other hand, they can be interchanged with one another. They are not therefore really complex; what symbolizes is simply the general way in which they are combined.

The combination of symbols in a tautology cannot possibly correspond to any one particular combination of their meanings—it corresponds to every possible combination; and therefore what symbolizes can't be the connexion of the symbols.

From the fact that I see that one spot is to the left of another, or that one colour is darker than another, it seems to follow that it is so; and if so, this can only be if there is an internal relation between the two; and we might express this by saying that the form of the latter is part of the form of the former. We might thus give a sense to the assertion that logical laws are forms of thought and space and time forms of intuition.

Different logical types can have nothing whatever in common. But the mere fact that we can talk of the possibility of a relation of n places, or of an analogy between one with two places and one with four, shews that relations with different numbers of places have something in common, that therefore the difference is not one of type, but like the difference between different names—something which depends on experience. This answers the question how we can know that we have really got the most general form of a proposition. We have only to introduce what is common to all relations of whatever number of places.

The relation of "I believe p" to "p" can be compared to the relation of '"p" says (besagt) p' to p: it is just as impossible that I should be a simple as that "p" should be.

- ↑ Note of the editor of the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project’s digital edition: The diagram originally drawn by Moore looked like this:

In the truth table notation (where the combinations of the truth values of individual propositions are displayed by means of a table and the two poles are indicated by “T” and “F” instead of “a” and “b” respectively) the equivalent of that diagram is as follows:

p p p ≡ ~(~p) T T T T F T F T F F F T This, however, does not correspond to the truth table of p ≡ ~(~p), which is instead as follows:

p p p ≡ ~(~p) T T T T F F F V F F F T The paper edition this digital edition is based upon faithfully reproduces Moore’s drawing. In this digital edition, instead, the original diagram was replaced by a corrected version which corresponds to this truth table.

See Michael A.R. Biggs. “Editing Wittgenstein’s Notes on Logic. Vol. 1.” Working Papers from the Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen, no. 11, 1996, § 1.8.