Blue Book: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 231: | Line 231: | ||

The contradiction which here seems to arise could be called a conflict between two different usages of a word, in this case the word “measure”. Augustine, we might say, thinks of the process of measuring a ''length'': say, the distance between two marks on a travelling band which passes us, and of which we can only see a tiny bit (the present) in front of us. Solving this puzzle will consist in comparing what we mean by “measurement” (the grammar of the word “measurement”) when applied to a distance on a travelling band with the grammar of that word when applied to time. The problem may seem simple, but its extreme difficulty is due to the fascination which the analogy between two similar structures in our language can exert on us. (It is helpful here to remember that it is sometimes almost impossible for a child to realise that one word can have two meanings). | The contradiction which here seems to arise could be called a conflict between two different usages of a word, in this case the word “measure”. Augustine, we might say, thinks of the process of measuring a ''length'': say, the distance between two marks on a travelling band which passes us, and of which we can only see a tiny bit (the present) in front of us. Solving this puzzle will consist in comparing what we mean by “measurement” (the grammar of the word “measurement”) when applied to a distance on a travelling band with the grammar of that word when applied to time. The problem may seem simple, but its extreme difficulty is due to the fascination which the analogy between two similar structures in our language can exert on us. (It is helpful here to remember that it is sometimes almost impossible for a child to realise that one word can have two meanings). | ||

Now it is clear that this problem about the concept of time asks for an answer given in the form of strict rules. The puzzle is about rules. – Take another example: Socrates' question: “What is knowledge?” Here the case is even clearer, as the discussion begins with the pupil giving an example of an {{BBB TS reference|Ts-309,43}} exact definition; and then analogous to this, a definition of the word “knowledge” is asked for. As the problem is put, it seems that there is something wrong with the ordinary use of the word “knowledge”. It appears, we don't know what it means, and that therefore, perhaps, we have no right to use it. We should reply: “There is no one exact usage of the word ‘knowledge’; but we can make up several such usages, which will more or less agree with the ways the word is actually | Now it is clear that this problem about the concept of time asks for an answer given in the form of strict rules. The puzzle is about rules. – Take another example: Socrates' question: “What is knowledge?” Here the case is even clearer, as the discussion begins with the pupil giving an example of an {{BBB TS reference|Ts-309,43}} exact definition; and then analogous to this, a definition of the word “knowledge” is asked for. As the problem is put, it seems that there is something wrong with the ordinary use of the word “knowledge”. It appears, we don't know what it means, and that therefore, perhaps, we have no right to use it. We should reply: “There is no one exact usage of the word ‘knowledge’; but we can make up several such usages, which will more or less agree with the ways the word is actually used”. | ||

The man who is philosophically puzzled sees a law in the way a word is used, and trying to apply this law consistently, comes up against cases where it leads to paradoxical results. Very often the way the discussion of such a puzzle runs is this: First the question is asked, “What is time?” This question makes it appear that what we want is a definition. We mistakenly think that a definition is what will remove the trouble; as in certain states of indigestion we feel a kind of hunger which cannot be removed by eating. The question is then answered by a wrong definition; say: “Time is the motion of the celestial bodies”. The next step is to see that this definition is unsatisfactory. But this only means that we don't use the word “time” synonymous with motion of the celestial bodies”. However in saying that the first definition is wrong, we are now tempted to think that we must replace it by a different one, the correct one. | The man who is philosophically puzzled sees a law in the way a word is used, and trying to apply this law consistently, comes up against cases where it leads to paradoxical results. Very often the way the discussion of such a puzzle runs is this: First the question is asked, “What is time?” This question makes it appear that what we want is a definition. We mistakenly think that a definition is what will remove the trouble; as in certain states of indigestion we feel a kind of hunger which cannot be removed by eating. The question is then answered by a wrong definition; say: “Time is the motion of the celestial bodies”. The next step is to see that this definition is unsatisfactory. But this only means that we don't use the word “time” synonymous with motion of the celestial bodies”. However in saying that the first definition is wrong, we are now tempted to think that we must replace it by a different one, the correct one. | ||

Revision as of 12:55, 6 August 2022

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Blue Book

This digital edition is a normalised version of Wittgenstein’s Nachlass Ts-309 (so-called Blue Book) produced with the Interactive Dynamic Presentation tool[N] provided by the Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen (WAB). This original-language text is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 70 years or fewer.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Blue Book

Template:BBB TS reference What is the meaning of a word?

Let us attack this question by asking, first, what is an explanation of the meaning of a word; what does the explanation of a word look like?

The way this question helps us is analogous to the way the question “how do we measure a length?” helps us to understand the problem, “what is length?”

The questions, “What is length?”, “What is meaning?”, “What is the number one?” etc., produce in us a mental cramp. We feel that we can't point to anything in reply to them and yet ought to point to something. (We are up against one of the great sources of philosophical bewilderment: we try to find a substance for a substantive.)

Asking first, “What's an explanation of meaning?” has two advantages. You in a sense bring the question “what is meaning?” down to earth. For, surely, to understand the meaning of “meaning” you ought also to understand the meaning of “explanation of meaning”. Roughly: “let's ask what the explanation of meaning is, for whatever that explains will be the meaning.” Studying the grammar of the expression “explanation of meaning” will teach you something about the grammar of the word “meaning” and will cure you of the temptation to look about you for something which you might call the “meaning”.

What one generally calls “explanations of the meaning of Template:BBB TS reference a word” can, very roughly, be divided into verbal and ostensive definitions. It will be seen later in what sense this division is only rough and provisional (and that it is, is an important point). The verbal definition, as it takes us from one verbal expression to another, in a sense gets us no further. In the ostensive definition however we seem to make a much more real step towards learning the meaning.

One difficulty which strikes us is that for many words in our language there do not seem to be ostensive definitions; e.g. for such words as “one”, “number”, “not”, etc.

Question: Need the ostensive definition itself be understood? – Can't the ostensive definition be misunderstood?

If the definition explains the meaning of a word, surely it can't be essential that you should have heard the word before. It is the ostensive definition's business to give it a meaning. Let us then explain the word “tove” by pointing to a pencil and saying “this is tove”. (Instead of “this is tove” I could here have said “this is called ‘tove’”. I point this out to remove, once and for all, the idea that the words of the ostensive definition predicate something of the defined; the confusion between the sentence “this is red”, attributing the colour red to something, and this ostensive definition “this is called ‘red’”.) Now the ostensive definition “this is tove” can be interpreted in all sorts of ways. I will give a few such interpretations and use English words with well established usage. The definition then can be interpreted to mean: – Template:BBB TS reference

- “This is a pencil”,

- “This is round”,

- “This is wood”,

- “This is one”,

- “This is hard”, etc. etc.

One might object to this argument that all these interpretations presuppose another word-language. And this objection is significant if by “interpretation” we only mean “Translation into a word-language”. – Let me give some hints which might make this clearer. Let us ask ourselves what is our criterion when we say that someone has interpreted the ostensive definition in a particular way. Suppose I give to an Englishman the ostensive definition “this is what the Germans call ‘Buch’”. Then, in the great majority of cases, at any rate, the English word “book” will come into the Englishman's mind. We may say he has interpreted “Buch” to mean “book”. The case will be different if e.g., we point to a thing which he has never seen before and say: “This is a banjo”. Possibly the word “guitar” will then come into his mind, possibly no word at all but the image of a similar instrument, possibly nothing at all. Supposing then I give him the order “now pick a banjo from amongst those things”. If he picks what we call a “banjo” we might say “he has given the word ‘banjo’ the correct interpretation”; if he picks some other instrument: – “he has interpreted ‘banjo’ to mean ‘string instrument’”.

We say “he has given the word ‘banjo’ this or that interpretation”, Template:BBB TS reference and are inclined to assume a definite act of interpretation besides the act of choosing.

Our problem is analogous to the following: – If I give someone the order “fetch me a red flower from that meadow”, how is he to know what sort of flower to bring, as I have only given him a word?

Now the answer one might suggest first is that he went to look for a red flower carrying a red image in his mind, and comparing it with the flowers to see which of them had the colour of the image. Now there is such a way of searching, and it is not at all essential that the image we use should be a mental one. In fact the process may be this: – I carry a chart co-ordinating names and coloured squares. When I hear the order “fetch me etc.” I draw my finger across the chart from the word “red” to a certain square, and I go and look for a flower which has the same colour as the square. But this is not the only way of searching and it isn't the usual way. We go, look about us, walk up to a flower and pick it, without comparing it to anything. To see that the process of obeying the order can be of this kind, consider the order “imagine a red patch”. You are not tempted in this case to think that before obeying you must have imagined a red patch to serve you as a pattern for the red patch which you were ordered to imagine.

Now you might ask “do we interpret the words before we obey the order?” And in some cases you will find that you do something which might be called interpreting before obeying, in some cases not. Template:BBB TS reference

It seems that there are certain definite mental processes bound up with the working of language; processes through which alone language can function. I mean the processes of understanding and meaning. The signs of our language seem dead without these mental processes; and it might seem that the only function of the signs is to induce such processes, and that these are the things we ought really to be interested in. Thus, if you are asked what is the relation between a name and the thing it names, you will be inclined to answer that the relation is a psychological one, and perhaps when you say this you think in particular of the mechanism of association. – We are tempted to think that the action of language consists of two parts; an inorganic part, the handling of signs, and an organic part, which we may call understanding these signs, meaning them, interpreting them, thinking. These latter activities seem to take place in a queer kind of medium, the mind; and the mechanism of the mind, the nature of which, it seems, we don't quite understand, can bring about effects which no material mechanism could. Thus e.g. a thought (which is such a mental process) can agree or disagree with reality: I am able to think of a man who isn't present; I am able to imagine him, “mean” him, in a remark which I make about him even if he is thousands of miles away or dead. “What a queer mechanism”, one might say, “the mechanism of wishing must be if I can wish that which will never happen”.

There is one way of avoiding at least partly the occult appearance of the process of thinking, and it is, to replace in these processes any working of the imagination by looking at real Template:BBB TS reference objects. Thus it may seem essential that, at least in certain cases, when I hear the word “red” with understanding, a red image should be before my mind's eye. But why should I not substitute seeing a red bit of paper for imagining a red patch? The visual image will only be the more vivid. You can easily imagine a man carrying a sheet of paper in his pocket on which the names of colours are coordinated with coloured patches. You may say that it would be a nuisance to carry such a table of samples about with you, and that the mechanism of association is what we always use instead of it. But this is irrelevant; and in many cases it is not even true. If, for instance, you were ordered to paint a particular shade of blue, called “Prussian Blue”, you might have to use a table to lead you from the word “Prussian Blue” to a sample of the colour, which would serve you as a copy.

We could perfectly well, for our purposes, replace every process of imagining by a process of looking at an object or by painting, drawing or modelling; and every process of speaking to oneself by speaking aloud or writing.

Frege ridiculed the formalist conception of mathematics by saying that the formalists confused the unimportant thing, the sign, with the important, the meaning. Surely, one wishes to say, mathematics does not treat of dashes on a bit of paper. Frege's idea could be expressed thus: the propositions of mathematics, if they were just complexes of dashes, would be dead and utterly uninteresting, whereas they obviously have a kind of life. And the same, of course, could be said of any proposition: Without a sense, or without the thought, a proposition would be an utterly Template:BBB TS reference dead and trivial thing. And further it seems clear that no adding of inorganic signs can make the proposition live. And the conclusion which one draws from this is that what must be added to the dead signs in order to make a live proposition is something immaterial with properties different from all mere signs.

But if we had to name anything which is the life of the sign, we should have to say that it was its use.

If the meaning of the sign (roughly, that which is of importance about the sign) is an image built up in our minds when we see or hear the sign, then first let us adopt the method we just described of replacing this mental image by seeing some sort of outward object, e.g. a painted or modelled image. Then why should the written sign plus this painted image be alive if the written sign alone was dead? – In fact, as soon as you think of replacing the mental image by, say, a painted one, and as soon as the image thereby loses its occult character, it ceases to seem to impart any life to the sentence at all. (It was in fact just the occult character of the mental process which you needed for your purposes.)

The mistake we are liable to make could be expressed thus: We are looking for the use of a sign, but we look for it as though it were an object co-existing with the sign. (One of the reasons for this mistake is again that we are looking for a “thing corresponding to a substantive.”)

The sign (the sentence) gets its significance from the system of signs, from the language to which it belongs. Roughly: understanding a sentence means understanding a language. Template:BBB TS reference

As a part of the system of language, one may say “the sentence has life”. But one is tempted to imagine that which gives the sentence life as something in an occult sphere, accompanying the sentence. But whatever would accompany it would for us just be another sign.

It seems at first sight that that which gives to thinking its peculiar character is that it is a train of mental states, and it seems that what is queer and difficult to understand about thinking is the processes which happen in the medium of the mind, processes possible only in this medium. The comparison which here forces itself upon us is that of the mental medium with the protoplasm of a cell, say, of an amoeba. We observe certain actions of the amoeba, its taking food by extending arms, its splitting up into similar cells, each of which grows and behaves like the original one. We say “of what a queer nature the protoplasm must be to act in such a way”, and perhaps we say that no physical mechanism could behave in this way, and that the mechanism of the amoeba must be of a totally different kind. In the same way we are tempted to say “the mechanism of the mind must be of a most peculiar kind to be able to do what the mind does.” But here we are making two mistakes. For what struck us as being queer about thought and thinking was not at all that it had curious effects which we were not yet able to explain (causally). Our problem, in other words, was not a scientific one; but a muddle felt as a problem.

Supposing we tried to construct a mind-model as a result of psychological investigations, a model which, as we should say, Template:BBB TS reference would explain the action of the mind. This model would be part of a psychological theory in the way in which a mechanical model of the ether can be part of a theory of electricity. (Such a model, by the way, is always part of the symbolism of a theory. Its advantage may be that it is seen at a glance and easily held in the mind. It has been said that a model, in a sense, dresses up the pure theory; that the naked theory is sentences or equations. This must be examined more closely later on.)

We may find that such a mind-model would have to be very complicated and intricate in order to explain the observed mental activities; and on this ground we might call the mind a queer kind of medium. But this aspect of the mind does not interest us. The problems which it may set are psychological problems, and the method of their solution is that of natural science.

Now if it is not the causal connections which we are concerned with, then the activities of the mind lie open before us. And when we are worried about the nature of thinking, the puzzlement which we wrongly interpret to be one about the nature of a medium is a puzzlement caused by the mystifying use of our language. This kind of mistake recurs again and again in philosophy, e.g. when we are puzzled about the nature of time; when time seems to us a queer thing. We are most strongly tempted to think that here are things hidden, something we can see from the outside but which we can't look into. And yet nothing of the sort is the case. It is not new facts about time which we want to know. All the facts that concern us lie open before us. But it is the use of the substantive “time” which mystifies us. If we look into Template:BBB TS reference the grammar of that word, we shall feel that it is no less astounding that man should have conceived of a deity of time than it would be to conceive of a deity of negation or disjunction.

It is misleading then to talk of thinking as of a “mental activity”. We may say that thinking is essentially the activity of operating with signs. This activity is performed by the hand, when we think by writing; by the mouth and larynx, when we think by speaking; and, if we think by imagining signs or pictures I can give you no agent that thinks. If then you say that in such cases the mind thinks, I would only draw your attention to the fact that you are using a metaphor, that here the mind is an agent in a different sense from that in which the hand can be said to be the agent in writing.

If again we talk about the locality where thinking takes place we have a right to say that this locality is the paper on which we write; or the mouth which speaks. And if we talk of the head or the brain as the locality of thought, this is using the expression “locality of thinking” in a different sense. Let us examine what are the reasons for calling the head the place of thinking. It is not our intention to criticize this form of expression, or to show that it is not appropriate. What we must do is: understand its working, its grammar, e.g. see what relation this grammar has to that of the expression “we think with our mouth”, or “we think with a pencil on a piece of paper”.

Perhaps the main reason why we are so strongly inclined to talk of the head as the locality of our thoughts is this: – the existence of the words “thinking” and “thought” alongside of the Template:BBB TS reference words denoting (bodily) activities, such as writing, speaking, etc. makes us look for an activity, different from these but analogous to them, corresponding to the word “thinking”. When words in our ordinary language have prima facie analogous grammars we are inclined to try to interpret them analogously; i.e. we try to make the analogy hold throughout. – We say, “The thought is not the same as the sentence; for an English and a French sentence, which are utterly different, can express the same thought”. And now, as the sentences are somewhere, we look for a place for the thought. (It is as though we looked for the place of the king of which the rules of chess treat, as opposed to the places of the various bits of wood, etc., the kings of the various sets.) – We say, “surely the thought is something; it is not nothing”; and all one can answer to this is, that the word “thought” has its use, which is of a totally different kind from the use of the word “sentence”.

Now does this mean that it is nonsensical to talk of a locality where thought takes place? Certainly not. This phrase has sense, if we give it sense. Now if we say “thought takes place in our heads”, what is the sense of this phrase soberly understood? I suppose it is that certain physiological processes correspond to our thoughts in such a way that if we know the correspondence we can, by observing these processes, find the thoughts. But in what sense can the physiological processes be said to correspond to thoughts, and in what sense can we be said to get the thoughts from the observation of the brain?

I suppose we imagine the correspondence to have been verified Template:BBB TS reference experimentally. Let us imagine such an experiment crudely. It consists in looking at the brain while the subject thinks. And now you may think that the reason why my explanation is going to go wrong is that of course the experimenter gets the thoughts of the subject only indirectly by being told them, the subject expressing them in some way or the other. But I will remove this difficulty by assuming that the subject is at the same time the experimenter, who is looking at his own brain, say by means of a mirror. (The crudity of this description in no way reduces the force of the argument.)

Then I ask you, is the subject-experimenter observing one thing or two things? (Don't say that he is observing one thing both from the inside and from the outside; for this does not remove the difficulty. We will talk of inside and outside later.) The subject-experimenter is observing a correlation of two phenomena. One of them he, perhaps, calls the thought. This may consist of a train of images, organic sensations, or, on the other hand of a train of the various visual, tactile and muscular experiences which he has in writing or speaking a sentence. – The other experience is one of seeing his brain work. Both these phenomena could correctly be called “expressions of thought”; and the question “where is the thought itself?” had better, in order to prevent confusion, be rejected as nonsensical. If however we do use the expression “the thought takes place in our heads”, we have given this expression its meaning by describing the experience which would justify the hypothesis “the thought takes place in our heads” by describing what we call the experience of observing Template:BBB TS reference the thought in our brain.

We easily forget that the word “locality” is used in many different senses and that there are many different kinds of statements about a thing which in a particular case, in accordance with general usage, we may call “specifications of the locality of the thing”. Thus it has been said of visual space that its place is in our head; and I think one has been tempted to say this, partly, by a grammatical misunderstanding.

I can say: “in my visual field I see the image of the tree to the right of the image of the tower” or “I see the image of the tree in the middle of the visual field”. And now we are inclined to ask, “and where do you see the visual field?” Now if the “where” is meant to ask for a locality in the sense in which we have specified the locality of the image of the tree, then I would draw your attention to the fact that you have not yet given this question sense; that is, that you have been proceeding by a grammatical analogy without having worked out the analogy in detail.

In saying that the idea of our visual field being located in our brain arose from a grammatical misunderstanding, I did not mean to say that we could not give sense to such a specification of locality. We could e.g., easily imagine an experience which we should describe by such a statement. Imagine that we looked at a group of things in this room, and while we looked, a probe was stuck into our brain, and it was found that if the point of the probe reached a particular point in our brain, then a particular small part of our visual field was thereby obliterated. In this way we might coordinate points of our brain to points of Template:BBB TS reference the visual image, and this might make us say that the visual field was seated in such-and-such a place in our brain. And if now we asked the question “Where do you see the image of this book?” the answer could be (as above) “To the right of that pencil”, or “In the left hand part of my visual field”, or again: “three inches behind my left eye”.

But what if someone said “I can assure you I feel the visual image to be two inches behind the bridge of my nose”; – what are we to answer him? Should we say that he is not speaking the truth, or that there cannot be such a feeling? What if he asks us “do you know all the feelings there are? How do you know there isn't such a feeling?”

What if the diviner tells us that when he holds the rod he feels that the water is five feet under the ground? or that he feels that a mixture of copper and gold is five feet under the ground? Suppose that to our doubts he answered: “You can estimate a length when you see it. Why shouldn't I have a different way of estimating it?”

If we understand the idea of such an estimation, we shall get clear about the nature of our doubts about the statements of the diviner, and of the man who said he felt the visual image behind the bridge of his nose.

There is the statement: “this pencil is five inches long”, and the statement, “I feel that this pencil is five inches long”, and we must get clear about the relation of the grammar of the first statement to the grammar of the second. To the statement “I feel in my hand that the water is three feet under the ground” Template:BBB TS reference we should like to answer: “I don't know what this means”. But the diviner would say: “surely you know what it means. You know what ‘three feet under the ground’ means, and you know what ‘I feel’ means.” But I should answer him: “I know what a word means in certain contexts. Thus I understand the phrase ‘three feet under the ground’, say, in the connections, ‘the measurement has shown that the water runs three feet under the ground’, ‘If we dig three feet deep we are going to strike water’, ‘the depth of the water is three feet by the eye’. But the use of the expression ‘a feeling in my hands of water being three feet under the ground’ has yet to be explained to me.”

We could ask the diviner “how did you learn the meaning of the word ‘three feet’?” We suppose by being shown such lengths, by having measured them and such like. Were you also taught to talk of a feeling of water being three feet under the ground, a feeling, say, in your hands? For if not, what made you connect the word “three feet” with a feeling in your hands? Supposing we had been estimating lengths by the eye, but had never spanned a length. How could we estimate a length in inches by spanning it? I.e., how could we interpret the experience of spanning in inches? The question is, what connection is there between, say, a tactile sensation and the experience of measuring a thing by means of a yard rod? This connection will show us what it means to “feel that a thing is six inches long”. Supposing the diviner said, “I have never learnt to correlate depth of water under the ground with feelings in my hand, but when I have a certain feeling of tension in my hands, the words “three feet” spring up in my Template:BBB TS reference mind.” We should answer “This is a perfectly good explanation of what you mean by ‘feeling the depth to be three feet’, and the statement that you feel this will have neither more, nor less, meaning than your explanation has given it. And if experience shows that the actual depth of the water always agrees with the words, ‘n feet’ which come into your mind, your experience will be very useful for determining the depth of water”. – But you see that the meaning of the words, “I feel the depth of the water to be n feet” had to be explained; it was not known when the meaning of the words “n feet” in the ordinary sense (i.e. in the ordinary contexts) was known. – We don't say that the man who tells us he feels the visual image two inches behind the bridge of his nose is telling a lie or talking nonsense. But we say that we don't understand the meaning of such a phrase. It combines well-known words but combines them in a way we don't yet understand. The grammar of this phrase has yet to be explained to us.

The importance of investigating the diviner's answer lies in the fact that we often think we have given a meaning to a statement P if only we assert “I feel (or I believe) that P is the case.” (We shall talk at a later occasion of Professor Hardy saying that Goldbach's theorem is a proposition because he can believe that it is true.) We have already said that by merely explaining the meaning of the words “three feet” in the usual way, we have not yet explained the sense of the phrase “feeling that water is three feet, etc.” Now we should not have felt these difficulties had the diviner said that he had learnt to estimate the depth of the Template:BBB TS reference water, say, by digging for water whenever he had a particular feeling and in this way correlating such feelings with measurements of depth. Now we must examine the relation of the process of learning to estimate with the act of estimating. The importance of this examination lies in this, that it applies to the relation between learning the meaning of a word and making use of the word. Or, more generally, that it shows the different possible relations between a rule given and its application.

Let us consider the process of estimating a length by the eye: It is extremely important that you should realise that there are a great many different processes which we call “estimating by the eye”.

Consider these cases: –

- (1) Someone asks “How did you estimate the height of this building?” I answer: “It has four storeys; I suppose each storey is about fifteen feet high; so it must be about sixty feet.”

- (2) In another case: “I roughly know what a yard at that distance looks like; so it must be about four yards long.”

- (3) Or again: “I can imagine a tall man reaching to about this point; so it must be about six feet above the ground.”

- (4) Or: “I don't know; it just looks like a yard.”

This latter case is likely to puzzle us. If you ask “what happened in this case when the man estimated the length?” the correct answer may be: “he looked at the thing and said ‘it looks one yard long’.” This may be all that has happened.

We said before that we should not have been puzzled about the Template:BBB TS reference diviner's answer if he had told us that he had learnt how to estimate depth. Now learning to estimate may, broadly speaking, be seen in two different relations to the act of estimating; either as a cause of the phenomenon of estimating; or as supplying us with a rule (a table, a chart, or some such thing) which we make use of when we estimate.

Supposing I teach someone the use of the word “yellow” by repeatedly pointing to a yellow patch and pronouncing the word. On another occasion I make him apply what he has learnt by giving him the order, “choose a yellow ball out of this bag”. What was it that happened when he obeyed my order? I say: “possibly just this: he heard my words and took a yellow ball from the bag.” Now you may be inclined to think that this couldn't possibly have been all; and the kind of thing that you would suggest is that he imagined something yellow when he understood the order, and then chose a ball according to his image. To see that this is not necessary remember that I could have given him the order, “Imagine a yellow patch”. Would you still be inclined to assume that he first imagines a yellow patch, just understanding my order, and then imagines a yellow patch to match the first? (Now I don't say that this is not possible. Only, putting it in this way immediately shows you that it need not happen. This, by the way, illustrates the method of philosophy.)

If we are taught the meaning of the word “yellow” by being given some sort of ostensive definition (a rule of the usage of the word) this teaching can be looked at in two different ways.

A. The teaching is a drill. This drill causes us to Template:BBB TS reference associate a yellow image, yellow things, with the word “yellow”. Thus when I give the order “Choose a yellow ball from this bag” the word “yellow” might have brought up a yellow image, or a feeling of recognition when the person's eye fell on the yellow ball. The drill of teaching could in this case be said to have built up a psychical mechanism. This, however, would only be a hypothesis or else a metaphor. We could compare teaching with installing an electric connection between a switch and a bulb. The parallel to the connection going wrong or breaking down should then be what we call forgetting the explanation or the meaning of the word. (We ought to talk further on about the meaning of “forgetting the meaning of a word”).

In so far as the teaching brings about the association, feeling of recognition, etc. etc., it is the cause of the phenomena of understanding, obeying, etc.; and it is a hypothesis that the process of teaching should be needed in order to bring about these effects. It is conceivable, in this sense, that all the processes of understanding, obeying, etc. should have happened without the person ever having been taught the language. (This, just now, seems extremely paradoxical).

B. The teaching may have supplied us with a rule which is itself involved in the processes of understanding, obeying, etc.; “involved”, however, meaning that the expression of this rule forms part of these processes.

We must distinguish between what one might call a “process being in accordance with a rule”, and, “a process involving a rule” (in the above sense). Template:BBB TS reference

Take an example. Some one teaches me to square cardinal numbers; he writes down the row

- 1 2 3 4,

and asks me to square them. (I will, in this case, again, replace any processes happening “in the mind” by processes of calculation on the paper). Suppose, underneath the first row of numbers, I then write: –

- 1 4 9 16.

What I wrote is in accordance with the general rule of squaring; but it obviously is in accordance with any number of other rules also; and amongst these it is not more in accordance with one than with another. In the sense in which before we talked about a rule being involved in a process, no rule was involved in this. Supposing that in order to get to my results, I calculated 1 × 1, 2 × 2, 3 × 3, 4 × 4 (that is, in this case, wrote down the calculations); these would again be in accordance with any number of rules. Supposing, on the other hand, in order to get to my results, I had written down what you may call “the rule of squaring”, say, algebraically. In this case this rule was involved in a sense in which no other rule was.

We shall say that the rule is involved in the understanding, obeying, etc., if, as I should like to express it, the symbol of the rule forms part of the calculation. (As we are not interested in where the processes of thinking, calculating, take place, we can, for our purposes, imagine the calculations being done entirely on paper. We are not concerned with the difference: internal, external.) Template:BBB TS reference

A characteristic example of the case B would be one in which the teaching supplied us with a table which we actually make use of in understanding, obeying, etc. If we are taught to play chess, we may be taught rules. If then we play chess, these rules need not be involved in the act of playing. But they may be. Imagine, e.g., that the rules were expressed in the form of a table; in one column the shapes of the chessmen are drawn, and in a parallel column we find diagrams showing the “freedom” (the legitimate moves) of the pieces. Suppose now that the way the game is played involves making the transition from the shape to the possible moves in the table, and then making one of these moves.

Teaching as the hypothetical history of our subsequent actions (understanding, obeying, estimating a length, etc.) drops out of our considerations. The rule which has been taught and is subsequently applied interests us only so far as it is involved in the application. A rule, so far as it interests us, does not act at a distance.

Suppose I pointed to a piece of paper and said, to some one: “this colour I call ‘red’”. Afterwards I give him the order: “now paint me a red patch”. I then ask him: “why, in carrying out my order, did you paint just this colour?” His answer could then be: “This colour (pointing to the sample which I have given him) was called red; and the patch I have painted has, as you see, the colour of the sample”. He has now given me a reason for carrying out the order in the way he did. Giving a reason for something one did or said means showing a way which leads to this Template:BBB TS reference action. In some cases it means telling the way which one has gone oneself; in others it means describing a way which leads there and is in accordance with certain accepted rules. Thus when asked, “why did you carry out my order by painting just this colour?” the answer could have described the way the person had actually taken to arrive at this particular shade. This would have been so if, hearing the word “red”, he had taken up the sample I had given him, labelled “red”, and had copied that sample when painting the patch. On the other hand he might have painted it “automatically” or from a memory image; but when asked to give the reason he might still point to the sample and show that it matched the patch he had painted. In this latter case the reason given would have been of the second kind; i.e. a justification post hoc.

Now if one thinks that there could be no understanding and obeying the order without a previous teaching, one thinks of the teaching as supplying a reason for doing what one did; as supplying the road one walks. Now there is the idea that if an order is understood and obeyed there must be a reason for our obeying it as we do; and in fact, a chain of reasons reaching back to infinity. This is as if one said: “Wherever you are, you must have got there from somewhere else, and to that previous place from another place; and so on ad infinitum”. (If, on the other hand, you had said, “wherever you are, you could have got there from another place ten yards away; and from that other place from a third, ten yards further away, and so on ad infinitum”, what then you would have stressed would have been the infinite possibility of making a step. Thus Template:BBB TS reference the idea of an infinite chain of reasons arises out of a confusion similar to this: – that a line of a certain length consists of an infinite number of parts because it is indefinitely divisible; i.e. because there is no end to the possibility of dividing it.)

If on the other hand you realise that the chain of actual reasons has a beginning, you will no longer be revolted by the idea of a case in which there is no reason for the way you obey the order. At this point, however, another confusion sets in, that between reason and cause. One is led into this confusion by the ambiguous use of the word “why”. Thus when the chain of reasons has come to an end and still the question “Why?” is asked one is then inclined to give a cause instead of a reason. If, e.g., to the question, “why did you paint just this colour when I told you to paint a red patch” you give the answer: “I have been shown a sample of this colour, and the word “red” was pronounced to me at the same time; and therefore this colour now always comes to my mind when I hear the word ‘red’”, then you have given a cause for your action and not a reason.

The proposition, that your action has such-and-such a cause, is a hypothesis. The hypothesis is well-founded if one has had a number of experiences which, roughly speaking, agree in showing that your action is the regular sequel of certain conditions which we then call causes of the action. In order to know the reason which you had for making a certain statement, for acting in a particular way, etc., no number of agreeing experiences is necessary, and the statement of your reason is not a hypothesis. The difference between the grammars of “reason” and “cause” is quite similar Template:BBB TS reference to that between the grammars of “motive” and “cause”. Of the cause one can say that one can't know it but one can only conjecture it. On the other hand one often says: “Surely I must know why I did it” talking of the motive. When I say: “we can only conjecture the cause but we know the motive” this statement will be seen later on to be a grammatical one. The “can” refers to a logical possibility.

The double use of the word “why”, asking for the cause and asking for the motive, together with the idea that we can know, and not only conjecture, our motives, gives rise to the confusion that a motive is a cause of which we are immediately aware, a cause “seen from the inside”, or a cause experienced. – Giving a reason is like giving a calculation by which you have arrived at a certain result.

Let us go back to the statement that thinking essentially consists in operating with signs. My point was that it is liable to mislead us if we say thinking is a mental activity. The question what kind of an activity thinking is is analogous to this: “Where does thinking take place?” We can answer: on paper, in our head, in the mind. None of these statements of locality gives the locality of thinking. The use of all these specifications is correct but we must not be misled by the similarity of their linguistic forms into a false conception of their grammar. As, e.g., when you say: “Surely, the real place of thought is in our head”. The same applies to the idea of thinking as an activity. It is correct to say that thinking is an activity of our writing hand, of our larynx, of our head, and Template:BBB TS reference of our mind, so long as we understand the grammar of these statements. And it is, furthermore, extremely important to realise how by misunderstanding the grammar of our expressions, we are led to think of one in particular of these statements as giving the real seat of the activity of thinking.

There is an objection to saying that thinking is some such thing as an activity of the hand. Thinking, one wants to say, is part of our “private experience”. It is not material, but an event in private consciousness. This objection is expressed in the question: “Could a machine think?” I shall talk about this at a later point, and now only refer you to an analogous question: “Can a machine have toothache?” You will certainly be inclined to say: “A machine can't have toothache”. All I will do now is to draw your attention to the use which you have made of the word “can” and to ask you: “Did you mean to say that all our past experience has shown that a machine never had toothache?” The impossibility of which you speak is a logical one. The question is: What is the relation between thinking (or toothache) and the subject which thinks, has toothache, etc. I shall say no more about this now.

If we say thinking is essentially operating with signs, the first question you might ask is: “What are signs?” – Instead of giving any kind of general answer to this question, I shall propose to you to look closely at particular cases which we should call “operating with signs”. Let us look at a simple example of operating with words. I give someone the order: “fetch me six apples from the grocer”, and I will describe a way of making use Template:BBB TS reference of such an order: The words “six apples” are written on a bit of paper, the paper is handed to the grocer, the grocer compares the word “apple” with labels on different shelves. He finds it to agree with one of the labels, counts from 1 to the number written on the slip of paper, and for every number counted takes a fruit off the shelf and puts it in a bag. – And here you have one use of words. I shall in the future again and again draw your attention to what I shall call language-games. These are processes of using signs simpler than those which usually occur in the use of our highly complicated everyday language. Language games are the forms of language with which a child begins to make use of words. The study of language-games is the study of primitive forms of language or primitive languages. If we want to study the problems of truth and falsehood, of the agreement and disagreement of propositions with reality, of the nature of assertion, assumption, and question, we shall with great advantage look at primitive forms of language in which these forms of thinking appear without the confusing background of highly complicated processes of thought. When we look at such simple forms of language, the mental mist which seems to enshroud our ordinary use of language disappears. We see activities, reactions, which are clear-cut and transparent. On the other hand we recognize in these simple processes forms of language not separated by a break from our more complicated ones. We see that we can build up the complicated forms from the primitive ones by gradually adding new forms.

Now what makes it difficult for us to take this line of investigation Template:BBB TS reference is our craving for generality.

This craving for generality is the resultant of a number of tendencies connected with particular philosophical confusions. There is –

(a) The tendency to look for something in common to all the entities which we commonly subsume under a general term. – We are inclined to think that there must be something in common to all games, say, and that this common property is the justification for applying the general term “game” to the various games; whereas games form a family the members of which have family likenesses. Some of them have the same nose, others the same eyebrows and others again the same way of walking; and these likenesses overlap. The idea of a general concept being a common property of its particular instances connects up with other primitive, too simple, ideas of the structure of language. It is comparable to the idea that properties are ingredients of the things which have the properties; e.g. that beauty is an ingredient of all beautiful things as alcohol is of beer and wine, and that we therefore could have pure beauty, unadulterated by anything that is beautiful.

(b) There is a tendency, rooted in our usual forms of expression, to think that the man who has learnt to understand a general term, say, the term “leaf”, has thereby come to possess a kind of general picture of a leaf, as opposed to pictures of particular leaves. He was shown different leaves when he learnt the meaning of the word “leaf”; and showing him the particular leaves was only a means to the end of producing “in him” an idea which we imagine to be some kind of general image. We say that he sees what is in common Template:BBB TS reference to all these leaves; and this is true if we mean that he can on being asked tell us certain features or properties which they have in common. But we are inclined to think that the general idea of a leaf is something like a visual image but one which only contains what is common to all leaves. (Galtonian composite photograph). This again is connected with the idea that the meaning of a word is an image, or a thing correlated to the word. (This roughly means, we are looking at words as though they all were proper names, and we then confuse the bearer of a name with the meaning of the name.)

(c) Again the idea we have of what happens when we get hold of the general idea “leaf”, “plant” etc. etc., is connected with the confusion between a mental state, meaning a state of a hypothetical mental mechanism, and a mental state meaning a state of consciousness (toothache, etc.).

(d) Our craving for generality has another main source: our preoccupation with the method of science. I mean the method of reducing the explanation of natural phenomena to the smallest possible number of primitive natural laws; and, in mathematics, of unifying the treatment of different topics by using a generalization. Philosophers constantly see the method of science before their eyes, and are irresistibly tempted to ask and answer questions in the way science does. This tendency is the real source of metaphysics, and leads the philosopher into complete darkness. I want to say here that it can never be our job to reduce anything to anything, or to explain anything. Philosophy really is “purely descriptive”. (Think of such questions as “Are there sense data?” Template:BBB TS reference And ask: What method is there of determining this? Introspection?)

Instead of “craving for generality” I could also have said “the contemptuous attitude towards the particular case”. If, e.g. someone tries to explain the concept of number and tells us that such-and-such a definition will not do or is clumsy because it only applies to, say, finite cardinals I should answer that the mere fact that he could have given such a limited definition makes this definition extremely important to us. (Elegance is not what we are trying for.) For why should what finite and transfinite numbers have in common be more interesting to us than what distinguishes them? Or rather, I should not have said “why should it be more interesting to us?” – it isn't; and this characterizes our way of thinking.

The attitude towards the more general and the more special in logic is connected with the usage of the word “kind” which is liable to cause confusion. We talk of kinds of numbers, kinds of propositions, kinds of proofs; and, also, of kinds of apples, kinds of paper, etc. In one sense what defines the kind are properties, like sweetness, hardness, etc. In the other the different kinds are different grammatical structures. A treatise on pomology may be called incomplete if there exist kinds of apples which it doesn't mention. Here we have a standard of completeness in nature. Supposing on the other hand there was a game resembling that of chess but simpler, no pawns being used in it. Should we call this game incomplete? Or should we call it a game “more complete than chess” which in some way contained chess but added new elements? The contempt for what seems the less general case in logic springs from the idea that it is incomplete. It is in fact Template:BBB TS reference confusing to talk of cardinal arithmetic as something special as opposed to something more general. Cardinal arithmetic bears no mark of incompleteness; nor does an arithmetic which is cardinal and finite. (There are no subtle distinctions between logical forms as there are between the tastes of different kinds of apples).

If we study the grammar, say, of the words, “wishing”, “thinking”, “understanding”, “meaning”, we shall not be dissatisfied when we have described various cases of wishing, thinking, etc. If someone said, “surely this is not all that one calls ‘wishing’”, we should answer, “certainly not, but you can build up more complicated cases if you like.” And after all, there is not one definite class of features which characterise all cases of wishing (at least not as the word is commonly used). If on the other hand you wish to give a definition of wishing, i.e., to draw a sharp boundary then you are free to draw it as you like; and this boundary will never entirely coincide with the actual usage, as this usage has no sharp boundary.

The idea that in order to get clear about the meaning of a general term one had to find the common element in all its applications, has shackled philosophical investigation; for it has not only led to no result, but also made the philosopher dismiss as irrelevant the concrete cases, which alone could have helped him to understand the usage of the general term. When Socrates asks the question, “what is knowledge?” he does not even regard it as a preliminary answer to enumerate cases of knowledge. If I wished to find out what sort of thing arithmetic is, I should be very content indeed to have investigated the case of a finite cardinal Template:BBB TS reference arithmetic. For

- (a) this would lead me on to all the more complicated cases,

- (b) a finite cardinal arithmetic is not incomplete, it has no gaps which are then filled in by the rest of arithmetic.

What happens if from 4 till 4.30 A expects B to come to his room? In one sense in which the phrase “to expect something from 4 to 4.30” is used it certainly does not refer to one process or state of mind going on throughout that interval, but is a great many different activities, and states of mind. If for instance I expect B to come to tea, what happens may be this: At four o'clock I look at my diary and see the name ‘B’ against today's date; I prepare tea for two; I think for a moment “does B smoke?” and put out cigarettes; towards 4.30 I begin to feel impatient; I imagine B as he will look when he comes into my room. All this is called “expecting B from 4 to 4.30”. And there are endless variations to this process which we all describe by the same expression. If one asks what the different processes of expecting someone to tea have in common, the answer is that there is no single feature in common to all of them, though there are many common features overlapping. These cases of expectation form a family; they have family likenesses which are not clearly defined.

There is a totally different use of the word “expectation” if we use it to mean a particular sensation. This use of the words like “wish”, “expectation”, etc., readily suggests itself. There is an obvious connection between this use and the one described above. There is no doubt that in many cases if we expect some one, in the first sense, some, or all, of the activities described are accompanied by a peculiar feeling, a tension; and it is natural Template:BBB TS reference to use the word “expectation” to mean this experience of tension.

There arises now the question: is this sensation to be called “the sensation of expectation”, or “the sensation of expectation that B will come?” In the first case to say that you are in a state of expectation admittedly does not fully describe the situation of expecting that so-and-so will happen. The second case is often rashly suggested as an explanation of the use of the phrase “expecting that so-and-so will happen”, and you may even think that with this explanation you are on safe ground, as every further question is dealt with by saying that the sensation of expectation is indefinable.

Now there is no objection to calling a particular sensation “the expectation that B will come”. There may even be good practical reasons for using such an expression. Only mark: – if we have explained the meaning of the phrase “expecting that B will come” in this way no phrase which is derived from this by substituting a different name for “B” is thereby explained. One might say that the phrase “expecting that B will come” is not a value of a function “expecting that x will come”. To understand this compare our case with that of the functional “I eat x”. We understand the proposition “I eat a chair” although we weren't specifically taught the meaning of the expression “eating a chair”.

The role which in our present case the name “B” plays in the expression “I expect B” can be compared with that which the name “Bright” plays in the expression “Bright's disease”. Compare the grammar of this word, when it denotes a particular kind of disease, with that of the expression “Bright's disease” when it Template:BBB TS reference means the disease which Bright has. I will characterize the difference by saying that the word “Bright” in the first case is an index in the complex name “Bright's disease”; in the second case I shall call it an argument of the function “x's disease”. One may say that an index alludes to something, and such an allusion may be justified in all sorts of ways. Thus calling a sensation “the expectation that B will come” is giving it a complex name and “B” possibly alludes to the man whose coming had regularly been preceded by the sensation.

Again we may use the phrase “expectation that B will come” not as a name but as a characteristic of certain sensations. We might, e.g., explain that a certain tension is said to be an expectation that B will come if it is relieved by B's coming. If this is how we use the phrase then it is true to say that we don't know what we expect until our expectation has been fulfilled (cf. Russell). But no one can believe that this is the only way or even the most common way of using the word “expect”. If I ask someone “whom do you expect?” and after receiving the answer ask again “are you sure that you don't expect someone else?” then, in most cases, this question would be regarded as absurd, and the answer will be something like “Surely, I must know whom I expect”.

One may characterise the meaning which Russell gives to the word “wishing” by saying that it means to him a kind of hunger. – It is a hypothesis that a particular feeling of hunger will be relieved by eating a particular thing. In Russell's way of using the word “wishing” it makes no sense to say “I wished for an apple but a pear has satisfied me”. But we do sometimes say this using Template:BBB TS reference the word “wishing” in a way different from Russell's. In this sense we can say that the tension of wishing was relieved without the wish being fulfilled; and also that the wish was fulfilled without the tension being relieved. That is, I may, in this sense, become satisfied without my wish having been satisfied.

Now one might be tempted to say that the difference which we are talking about simply comes to this, that in some cases we know what we wish and in others we don't. There are certainly cases in which we say, “I feel a longing, though I don't know what I'm longing for” or, “I feel a fear, but I don't know what I'm afraid of”, or again: “I feel fear, but I'm not afraid of anything in particular”. Template:BBB TS reference

Now we may describe these cases by saying that we have certain sensations not referring to objects. The phrase “not referring to objects” introduces a grammatical distinction. If in characterising such sensations we use verbs like “fearing”, “longing”, etc., these verbs will be intransitive; “I fear” will be analogous to “I cry”. We may cry about something, but what we cry about is not a constituent of the process of crying; that is to say, we could describe all that happens when we cry without mentioning what we are crying about.

Suppose now that I suggested we should use the expression “I feel fear”, and similar ones, in a transitive way only. Whenever before we said “I have a sensation of fear” (intransitively) we will now say “I am afraid of something, but I don't know of what”. Is there an objection to this terminology?

We may say: “There isn't, except that we are then using the word “to know” in a queer way”. Consider this case: – we have a general undirected feeling of fear. Later on, we have an experience which makes us say, “Now I know what I was afraid of. I was afraid of so-and-so happening”. Is it correct to describe my first feeling by an intransitive verb, or should I say that my fear had an object although I did not know that it had one? Both these forms of description Template:BBB TS reference can be used. To understand this examine the following examples: – It might be found practical to call a certain state of decay in a tooth, not accompanied by what we commonly call toothache, “unconscious toothache” and to use in such a case the expression that we have toothache, but don't know it. It is in just this sense that psychoanalysis talks of unconscious thoughts, acts of volition, etc. Now is it wrong in this sense to say that I have toothache but don't know it? There is nothing wrong about it, as it is just a new terminology and can at any time be retranslated into ordinary language. On the other hand it obviously makes use of the word “to know” in a new way. If you wish to examine how this expression is used it is helpful to ask yourself “what in this case is the process of getting to know like?” “What do we call ‘getting to know’ or, ‘finding out’?”

It isn't wrong, according to our new convention, to say “I have unconscious toothache”. For what more can you ask of your notation than that it should distinguish between a bad tooth which doesn't give you toothache and one which does? But the new expression misleads us by calling up pictures and analogies which make it difficult for us to go through with our convention. And it is extremely difficult to discard Template:BBB TS reference these pictures unless we are constantly watchful; particularly difficult when, in philosophising, we contemplate what we say about things. Thus, by the expression, “unconscious toothache” you may either be mislead into thinking that a stupendous discovery has been made, a discovery which in a sense altogether bewilders our understanding; or else you may be extremely puzzled by the expression (the puzzlement of philosophy) and perhaps ask such a question as “How is unconscious toothache possible?” You may then be tempted to deny the possibility of unconscious toothache; but the scientist will tell you that it is a proved fact that there is such a thing, and he will say it like a man who is destroying a common prejudice. He will say: “Surely it's quite simple; there are other things which you don't know of, and there can also be toothache which you don't know of. It is just a new discovery”. You won't be satisfied, but you won't know what to answer. This situation constantly arises between the scientists and the philosophers.

In such a case we may clear the matter up by saying: “Let's see how the word “unconscious”, “to know”, etc. etc., is used in this case, and how it's used in others”. How far does the analogy between these uses go? We shall also try to construct new notations, in order to break the spell of those which we are accustomed to.

We said that it was a way of examining the grammar (the use) of the word “to know”, to ask ourselves what, in the particular case we are examining, we should call “getting to know”. There Template:BBB TS reference is a temptation to think that this question is only vaguely relevant, if relevant at all, to the question: “what is the meaning of the word ‘to know’?” We seem to be on a side-track when we ask the question “What is it like in this case ‘to get to know’?” But this question really is a question concerning the grammar of the word “to know”, and this becomes clearer if we put it in the form: “What do we call ‘getting to know’?” It is part of the grammar of the word “chair” that this is what we call “to sit on a chair”, and it is a part of the grammar of the word “meaning” that this is what we call “explanation of a meaning”; in the same way to explain my criterion for another person's having toothache is to give a grammatical explanation about the word “toothache” and, in this sense, “an explanation concerning the meaning of the word ‘toothache.’”

When we learnt the meaning of the phrase “so-and-so has toothache” we were pointed out certain kinds of behaviour of those who were said to have toothache. As an instance of these kinds of behaviour let us take, holding your cheek. Suppose that by observation I found that in certain cases whenever these first criteria told me a person had toothache, a red patch appeared on the person's cheek. Supposing I now said to someone “I see A has toothache, he's got a red patch on his cheek”. He may ask me “How do you know A has toothache when you see a red patch?” I should then point out that certain phenomena had always coincided with the appearance of the red patch.

Now one may go on and ask: “How do you know that he has got Template:BBB TS reference toothache when he holds his cheek?” The answer to this might be, “I say, he has toothache when he holds his cheek because I hold my cheek when I have toothache”. But what if we went on asking: – “And why do you suppose that toothache corresponds to his holding his cheek just because your toothache corresponds to your holding your cheek?” You will be at a loss to answer this question and find that here we strike rock bottom, that is we have come down to conventions. (If you suggest as an answer to the last question that, whenever we've seen people holding their cheeks and asked them “what's the matter”, they have answered, “I have toothache”, – remember that this experience only co-ordinates holding your cheek with saying certain words.)

Let us introduce two antithetical terms in order to avoid certain elementary confusions: To the question “How do you know that so-and-so is the case”, we sometimes answer by giving “criteria” and sometimes by giving “symptoms”. If medical science calls angina an inflammation caused by a particular bacillus, and we ask in a particular case “why do you say this man has got angina?” then the answer “I have found the bacillus so-and-so in his blood” gives us the criterion, or what we may call the defining criterion of angina. If on the other hand the answer was, “His throat is inflamed”, this might give us a symptom of angina. I call “symptom” a phenomenon of which experience has taught us that it coincided, in some way or other, with the phenomenon which is our defining criterion. Then to say, “A man has angina” if this bacillus is found in him is a tautology Template:BBB TS reference or it is a loose way of stating the definition of “angina”. But to say, “A man has angina whenever he has an inflamed throat” is to make a hypothesis.

In practice, if you were asked which phenomenon is the defining criterion and which is a symptom, you would in most cases be unable to answer this question except by making an arbitrary decision ad hoc. It may be practical to define a word by taking one phenomenon as the defining criterion, but we shall easily be persuaded to define the word by means of what, according to our first use, was a symptom. Doctors will use names of diseases without ever deciding which phenomena are to be taken as criteria and which as symptoms; and this need not be a deplorable lack of clarity. For remember that in general we don't use language according to strict rules – it hasn't been taught us by means of strict rules, either. We, in our discussions on the other hand, constantly compare language with a calculus proceeding according to exact rules.

This is a very one-sided way of looking at language. In practice we very rarely use language as such a calculus. For not only do we not think of the rules of usage – of definitions, etc. – while using language, but when we are asked to give such rules in most cases we aren't able to do so. We are unable clearly to circumscribe the concepts we use; not because we don't know their real definition, but because there is no real “definition” to them. To suppose that there must be would be like supposing that whenever children play with a ball they play a Template:BBB TS reference game according to strict rules.

When we talk of language as a symbolism used in an exact calculus, that which is in our mind can be found in the sciences and in mathematics. Our ordinary use of language conforms to this standard of exactness only in rare cases. Why then do we in philosophizing constantly compare our use of words with one following exact rules? The answer is that the puzzles which we try to remove always spring from just this attitude towards language.

Consider as an example the question “What is time?” as Saint Augustine and others have asked it. At first sight what this question asks for is a definition, but then immediately the question arises: “What should we gain by a definition, as it can only lead us to other undefined terms?” And why should one be puzzled just by the lack of a definition of time, and not by the lack of a definition of “chair”? Why shouldn't we be puzzled in all cases where we haven't got a definition? Now a definition often clears up the grammar of a word. And in fact it is the grammar of the word “time” which puzzles us. We are only expressing this puzzlement by asking a slightly misleading question, the question: “What is … ?” This question is an utterance of unclarity, of mental discomfort; and it is comparable with the question “Why?” as children so often ask it. This too is an expression of a mental discomfort, and doesn't necessarily ask for either a cause or a reason. (Hertz, Principles of Mechanics). Now the puzzlement about the grammar of the word Template:BBB TS reference “time” arises from what one might call apparent contradictions in that grammar.

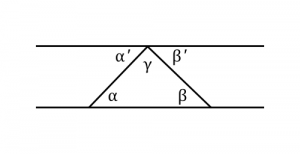

It was such a “contradiction” which puzzled Saint Augustine when he argued: How is it possible that one should measure time? For the past can't be measured, as it is gone by; and the future can't be measured because it has not yet come. And the present can't be measured because it has no extension.

The contradiction which here seems to arise could be called a conflict between two different usages of a word, in this case the word “measure”. Augustine, we might say, thinks of the process of measuring a length: say, the distance between two marks on a travelling band which passes us, and of which we can only see a tiny bit (the present) in front of us. Solving this puzzle will consist in comparing what we mean by “measurement” (the grammar of the word “measurement”) when applied to a distance on a travelling band with the grammar of that word when applied to time. The problem may seem simple, but its extreme difficulty is due to the fascination which the analogy between two similar structures in our language can exert on us. (It is helpful here to remember that it is sometimes almost impossible for a child to realise that one word can have two meanings).

Now it is clear that this problem about the concept of time asks for an answer given in the form of strict rules. The puzzle is about rules. – Take another example: Socrates' question: “What is knowledge?” Here the case is even clearer, as the discussion begins with the pupil giving an example of an Template:BBB TS reference exact definition; and then analogous to this, a definition of the word “knowledge” is asked for. As the problem is put, it seems that there is something wrong with the ordinary use of the word “knowledge”. It appears, we don't know what it means, and that therefore, perhaps, we have no right to use it. We should reply: “There is no one exact usage of the word ‘knowledge’; but we can make up several such usages, which will more or less agree with the ways the word is actually used”.

The man who is philosophically puzzled sees a law in the way a word is used, and trying to apply this law consistently, comes up against cases where it leads to paradoxical results. Very often the way the discussion of such a puzzle runs is this: First the question is asked, “What is time?” This question makes it appear that what we want is a definition. We mistakenly think that a definition is what will remove the trouble; as in certain states of indigestion we feel a kind of hunger which cannot be removed by eating. The question is then answered by a wrong definition; say: “Time is the motion of the celestial bodies”. The next step is to see that this definition is unsatisfactory. But this only means that we don't use the word “time” synonymous with motion of the celestial bodies”. However in saying that the first definition is wrong, we are now tempted to think that we must replace it by a different one, the correct one.

Compare with this the case of the definition of number. Here the explanation that a number is the same thing as a numeral satisfies that craving for a definition. And it is very Template:BBB TS reference difficult not to ask: “Well, if it isn't the numeral, what is it?”

Philosophy, as we use the word, is a fight against the fascination which forms of expression exert upon us.

I want you to remember that words have those meanings which we have given them; and we give them meanings by explanations. I may have given a definition of a word and used the word accordingly, or those who taught me the use of the word may have given me the explanation. Or else we might, by explanation of a word, mean the explanation which, on being asked, we are ready to give. That is, if we are ready to give an explanation; in most cases we aren't. Many words in this sense then don't have a strict meaning. But this is not a defect. To think it is would be like saying that the light of my reading lamp is no real light at all because it has no sharp boundary.

Philosophers very often talk about investigating, analysing, the meaning of words. But let's not forget that a word hasn't got a meaning given to it, as it were, by a power independent of us, so that there can be a kind of scientific investigation into what the word really means. A word has the meaning someone has given to it.

There are words with several clearly defined meanings. It is easy to tabulate these meanings. And there are words of which one might say: they are used in a thousand different ways which gradually merge into one another. No wonder that we can't tabulate strict rules for their use. Template:BBB TS reference

It is wrong to say that in philosophy we consider an ideal language as opposed to our ordinary one. For this makes it appear as though we thought we could improve on ordinary language. But ordinary language is all right. Whenever we make up “ideal languages” it is not in order to replace our ordinary language by them; but just to remove some trouble, caused in someone's mind by thinking that he has got hold of the exact use of a common word. That is also why our method is not merely to enumerate actual usages of words, but rather deliberately to invent new ones, some of them because of their absurd appearance.

When we say that by our method we try to counteract the misleading effect of certain analogies, it is important that you should understand that the idea of an analogy being misleading is nothing sharply defined. No sharp boundary can be drawn round the cases in which we should say that a man was misled by an analogy. The use of expressions constructed on analogical patterns stresses analogies between cases often far apart. And by doing this these expressions may be extremely useful. It is, in most cases, impossible to show an exact point where an analogy begins to mislead us. Every particular notation stresses some particular point of view. If, e.g., we call our investigations “philosophy”, this title, on the one hand, seems appropriate, on the other hand it certainly has misled people. (One might say that the subject we are dealing with is one of the heirs of the subject which we used to call “philosophy”.) The cases in which particularly, we wish to say that someone Template:BBB TS reference is misled by a form of expression are those in which we would say: “he wouldn't talk as he does if he were aware of this difference in the grammar of such-and-such words, or if he were aware of this other possibility of expression” and so on. Thus we may say of some philosophizing mathematicians that they are obviously not aware of the difference between the many different usages of the word “proof”; and that they are not clear about the difference between the uses of the word “kind”, when they talk of kinds of numbers, kinds of proofs, as thought the word “kind” here meant the same thing as in the context, “kinds of apples”. Or, we may say, they are not aware of the different meanings of the word “discovery”, when in one case we talk of the discovery of the construction of the pentagon and in the other case of the discovery of the South Pole.