Brown Book: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 837: | Line 837: | ||

I am tempted to say, “This isn't just a scribble, but it's ''this'' particular face.” – But I can't say, “I see ''this'' as ''this'' face”, but ought to say, “I see this as ''a'' face.” But I feel I want to say, “I don't see this as ''a'' face, I see it as ''this'' face!” But in the second half of this sentence the word “face” is redundant, and it should have run, “I don't see this as a face, I see it like ''this''.” | I am tempted to say, “This isn't just a scribble, but it's ''this'' particular face.” – But I can't say, “I see ''this'' as ''this'' face”, but ought to say, “I see this as ''a'' face.” But I feel I want to say, “I don't see this as ''a'' face, I see it as ''this'' face!” But in the second half of this sentence the word “face” is redundant, and it should have run, “I don't see this as a face, I see it like ''this''.” | ||

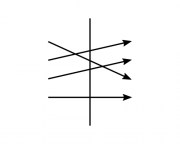

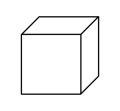

Suppose I said, “I see this scribble like ''this''”, and while saying “this scribble” I look at it as a mere scribble, and while saying “like ''this''”, I see the face, – this would come to something like saying, “What at one time appears to me like this at another appears to me like that”, and here the “this” and the “that” would be accompanied by the two different ways of seeing. – But we must ask ourselves in what game is this sentence with the processes accompanying it to be used. E.g., whom am I telling this? Suppose the answer is, “I'm saying it to myself.” But that is not enough. We are here in the grave danger of believing that we know what to do with a sentence if it looks more or less like one of the common sentences of our language. But here in order not to be deluded we have to ask ourselves: What is the use, say, of the words “this” and “that”? – or rather, What are the different uses which we make of them? What we call their meaning the meaning of these words is {{Brown Book Ts reference|Ts-310,145}} not anything which they have got in them or which is fastened to them irrespective of what use we make of them. Thus it is one use of the word “this” to go along with a gesture pointing to something: We say, “I am seeing the square with the diagonals like this”, pointing to a swastika. And referring to the square with diagonals I might have said, “What at one time appears to me like this [[File:Brown Book 2-Ts310,134d.png|80px|link=]] at another time appears to me like that [[File:Brown Book 2-Ts310,134e.png|80px|link=]].” And this is certainly not the use we made of the sentence in the above case. – One might think the whole difference between the two cases is this, that in the first the pictures are mental, in the second, real drawings. We should here ask ourselves in what sense we can call mental images pictures, for in some ways they are comparable to drawn or painted pictures, and in others not. It is, e.g., one of the essential points about the use of a “material” picture that we say that it remains the same not only on the ground that it seems to us to be the same, that we remember that it looked before as it looks now. In fact we shall say under certain circumstances that the picture hasn't changed although it seems to have changed; and we say it hasn't changed because it has been kept in a certain way, certain influences have been kept out. Therefore the expression, “The picture hasn't changed”, is used in a different way when we talk of a material picture on the one hand, and of a mental one on the other. Just as the statement, “These ticks follow at equal intervals”, has got one grammar if the ticks are the tick of a pendulum and the criterion for their regularity is the result of measurements which we have made on our apparatus, and another grammar if the ticks are ticks which {{Brown Book Ts reference|Ts-310,146}} we imagine. I might for instance ask the question: When I said to myself, “What at one time appears to me like this, at another … ”, did I recognize the two aspects, this and that, as the same which I got on previous occasions? Or were they new to me and I tried to remember them for future occasions? Or was all that I meant to say, “I can change the aspect of this figure”? | Suppose I said, “I see this scribble like ''this''”, and while saying “this scribble” I look at it as a mere scribble, and while saying “like ''this''”, I see the face, – this would come to something like saying, “What at one time appears to me like this at another appears to me like that”, and here the “this” and the “that” would be accompanied by the two different ways of seeing. – But we must ask ourselves in what game is this sentence with the processes accompanying it to be used. E.g., whom am I telling this? Suppose the answer is, “I'm saying it to myself.” But that is not enough. We are here in the grave danger of believing that we know what to do with a sentence if it looks more or less like one of the common sentences of our language. But here in order not to be deluded we have to ask ourselves: What is the use, say, of the words “this” and “that”? – or rather, What are the different uses which we make of them? What we call their meaning //the meaning of these words// is {{Brown Book Ts reference|Ts-310,145}} not anything which they have got in them or which is fastened to them irrespective of what use we make of them. Thus it is one use of the word “this” to go along with a gesture pointing to something: We say, “I am seeing the square with the diagonals like this”, pointing to a swastika. And referring to the square with diagonals I might have said, “What at one time appears to me like this [[File:Brown Book 2-Ts310,134d.png|80px|link=]] at another time appears to me like that [[File:Brown Book 2-Ts310,134e.png|80px|link=]].” And this is certainly not the use we made of the sentence in the above case. – One might think the whole difference between the two cases is this, that in the first the pictures are mental, in the second, real drawings. We should here ask ourselves in what sense we can call mental images pictures, for in some ways they are comparable to drawn or painted pictures, and in others not. It is, e.g., one of the essential points about the use of a “material” picture that we say that it remains the same not only on the ground that it seems to us to be the same, that we remember that it looked before as it looks now. In fact we shall say under certain circumstances that the picture hasn't changed although it seems to have changed; and we say it hasn't changed because it has been kept in a certain way, certain influences have been kept out. Therefore the expression, “The picture hasn't changed”, is used in a different way when we talk of a material picture on the one hand, and of a mental one on the other. Just as the statement, “These ticks follow at equal intervals”, has got one grammar if the ticks are the tick of a pendulum and the criterion for their regularity is the result of measurements which we have made on our apparatus, and another grammar if the ticks are ticks which {{Brown Book Ts reference|Ts-310,146}} we imagine. I might for instance ask the question: When I said to myself, “What at one time appears to me like this, at another … ”, did I recognize the two aspects, this and that, as the same which I got on previous occasions? Or were they new to me and I tried to remember them for future occasions? Or was all that I meant to say, “I can change the aspect of this figure”? | ||

The danger of delusion which we are in becomes most clear if we propose to ourselves to give the aspects “this” and “that” names, say A and B. For we are most strongly tempted to imagine that giving a name consists in correlating in a peculiar and rather mysterious way a sound (or other sign) with something. How we make use of this peculiar correlation then seems to be almost a secondary matter. (One could almost imagine that naming was done by a peculiar sacramental act, and that this produced some magic relation between the name and the thing.) | The danger of delusion which we are in becomes most clear if we propose to ourselves to give the aspects “this” and “that” names, say A and B. For we are most strongly tempted to imagine that giving a name consists in correlating in a peculiar and rather mysterious way a sound (or other sign) with something. How we make use of this peculiar correlation then seems to be almost a secondary matter. (One could almost imagine that naming was done by a peculiar sacramental act, and that this produced some magic relation between the name and the thing.) | ||

Revision as of 12:49, 29 July 2023

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Brown Book

This digital edition is a normalised version of Wittgenstein’s Nachlass Ts-310 (so-called Brown Book) produced with the Interactive Dynamic Presentation tool[N] provided by the Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen (WAB). This original-language text is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 70 years or fewer.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Brown Book

Part I

|(Ts-310,1) Augustine, in describing his learning of language, says that he was taught to speak by learning the names of things. It is clear that whoever says this has in mind the way in which a child learns such words as “man”, “sugar”, “table”, etc. He does not primarily think of such words as “today”, “not”, “but”, “perhaps”.

Suppose a man described a game of chess, without mentioning the existence and operations of the pawns. His description of the game as a natural phenomenon will be incomplete. On the other hand we may say that he has completely described a simpler game. In this sense we can say that Augustine's description of learning the language was correct for a simpler language than ours. Imagine this language: –

1). Its function is the communication between a builder A & his man B. B has to reach A building stones. There are cubes, bricks, slabs, beams, columns. The language consists of the words “cube”, “brick”, “slab”, “column”. A calls out one of these words, upon which B brings a stone of a certain shape. Let us imagine a society in which this is the only system of language. The child learns this language from the grown-ups by being trained to its use. I am using the word “trained” in a way strictly analogous to that in which we talk of an animal being trained to do certain things. It is done by means of example, reward, punishment, and such like. Part of this training is that we point to a building stone, direct the attention of the child towards it, & pronounce a word. I will call this procedure demonstrative teaching of words. In the actual |(Ts-310,2) use of this language, one man calls out the words as orders, the other acts according to them. But learning and teaching this language will contain this procedure: The child just “names” things, that is, he pronounces the words of the language when the teacher points to the things. In fact, there will be a still simpler exercise: The child repeats words which the teacher pronounces.

(Note: Objection: The word “brick” in language 1) has not the meaning which it has in our language. – This is true if it means that in our language there are usages of the word “brick!” different from our usages of this word in language 1). But don't we sometimes use the word “brick!” in just this way? Or should we say that when we use it, it is an elliptical sentence, a shorthand for “Bring me a brick”? Is it right to say that if we say “brick!” we mean “Bring me a brick”? Why should I translate the expression “brick!” into the expression, “Bring me a brick”? And if they are synonymous, why shouldn't I say: If he says “brick!” he means “brick!” … ? Or: Why shouldn't he be able to mean just “brick!” if he is able to mean “Bring me a brick”, unless you wish to assert that while he says aloud “brick!” he as a matter of fact always says in his mind, to himself, “Bring me a brick”? But what reason could we have to assert this? Suppose someone asked: If a man gives the order, “Bring me a brick”, must he mean it as four words, or can't he mean it as one composite word synonymous with the one word “brick!”? One is tempted to answer: He means all four words if in his language he uses that sentence in contrast with other |(Ts-310,3) sentences in which these words are used, such as, for instance, “Take these two bricks away”. But what if I asked, “But how is his sentence contrasted with these others? Must he have thought them simultaneously, or shortly before or after, or is it sufficient that he should have one time learnt them, etc.?” When we have asked ourselves this question, it appears that it is irrelevant which of these alternatives is the case. And we are inclined to say that all that is really relevant is that these contrasts should exist in the system of language which he is using, and that they need not in any sense be present in his mind when he utters his sentence. Now compare this conclusion with our original question. When we asked it, we seemed to ask a question about the state of mind of the man who says the sentence, whereas the idea of meaning which we arrived at in the end was not that of a state of mind. We think of the meaning of signs sometimes as states of mind of the man using them, sometimes as the role which these signs are playing in a system of language.The connection between these two ideas is that the mental experiences which accompany the use of a sign undoubtedly are caused by our usage of the sign in a particular system of language. William James speaks of specific feelings accompanying the use of such words as “&”, “if”, “or”. And there is no doubt that at least certain gestures are often connected with such words, as a collecting gesture with “and”, & a dismissing gesture with “not”. And there obviously are visual and muscular sensations connected with these gestures. On the other hand it is clear enough that these sensations do not accompany every use of the word “not”, and “&”. If in some language the word “but” meant what “not” means in English, it is clear that we should not compare the meanings of these two |(Ts-310,4) words by comparing the sensations which they produce. Ask yourself what means we have of finding out the feelings which they produce in different people and on different occasions. Ask yourself: “When I said, ‘Give me an apple & a pear, & leave the room’, had I the same feeling when I pronounced the two words ‘&’?” But we do not deny that the people who use the word “but” as “not” is used in English will broadly speaking have similar sensations accompanying the word “but” as the English have when they use “not”. And the word “but” in the two languages will on the whole be accompanied by different sets of experiences.)

2). Let us now look at an extension of language 1). The builder's man knows by heart the series of words from one to ten. On being given the order, “Five slabs!”, he goes to where the slabs are kept, says the words from one to five, takes up a plate for each word, & carries them to the builder. Here both the parties use the language by speaking the words. Learning the numerals by heart will be one of the essential features of learning this language. The use of the numerals will again be taught demonstratively. But now the same word, e.g., “three”, will be taught either by pointing to slabs, or to bricks, or to columns, etc. And on the other hand, different numerals, will be taught by pointing to groups of stones of the same shape.

(Remark: We stressed the importance of learning the series of numerals by heart because there was no feature comparable to this in the learning of language 1). And this shews us that by introducing numerals we have introduced an entirely different

|(Ts-310,5) kind of instrument into our language. The difference of kind is much more obvious when we contemplate such a simple example than when we look at our ordinary language with innumerable kinds of words all looking more or less alike when they stand in the dictionary. ‒ ‒

What have the demonstrative explanations of the numerals in common with those of the words “slab”, “column”, etc. except a gesture and pronouncing the words? The way such a gesture is used in the two cases is different. This difference is blurred if one says, “In one case we point to a shape, in the other we point to a number”. The difference becomes obvious and clear only when we contemplate a complete example (i.e., the example of a language completely worked out in detail).)

3). Let us introduce a new instrument of communication, – a proper name. This is given to a particular object (a particular building stone) by pointing to it and pronouncing the name. If A calls the name, B brings the object. The demonstrative teaching of a proper name is different again from the demonstrative teaching in the cases 1) & 2).

(Remark: This difference does not lie, however, in the act of pointing and pronouncing the word or in any mental act (meaning)﹖ accompanying it, but in the role which the demonstration (pointing & pronouncing) plays in the whole training and in the use which is made of it in the practice of communication by means of this language. One might think that the difference could be described by saying that in the different cases we point to different kinds of objects. But suppose I point with |(Ts-310,6) my hand to a blue jersey. How does pointing to its colour differ from pointing to its shape? – We are inclined to say the difference is that we mean something different in the two cases. And “meaning” here is to be some sort of process taking place while we point. What particularly tempts us to this view is that a man on being asked whether he pointed to the colour or the shape is, at least in most cases, able to answer this & to be certain that his answer is correct. If on the other hand, we look for two such characteristic mental acts as meaning the colour and meaning the shape, etc., we aren't able to find any, or at least none which must always accompany pointing to colour, pointing to shape, respectively. We have only a rough idea of what it means to concentrate one's attention on the colour as opposed to the shape, or vice versa. The difference one might say does not lie in the act of demonstration, but rather in the surrounding of that act in the use of the language.)

4). On being ordered “This slab!”, B brings the plate to which A points. On being ordered, “Plate, there!”, he carries a plate to the place indicated. Is the word “there” taught demonstratively? Yes & no! When a person is trained in the use of the word “there”, the teacher will in training him make the pointing gesture and pronounce the word “there”. But should we say that thereby he gives a place the name “there”? Remember that the pointing gesture in this case is part of the practice of communication itself.

(Remark: It has been suggested that such words as “there”, |(Ts-310,7) “here”, “now”, “this” are the “real proper names” as opposed to what in ordinary life we call proper names, & in the view I am referring to, can only be called so crudely. There is a widespread tendency to regard what in ordinary life is called a proper name only as a rough approximation of what ideally could be called so. Compare Russell's idea of the “individual”. He talks of individuals as the ultimate constituents of reality, but says that it is difficult to say which things are individuals. The idea is that further analysis has to reveal this. We, on the other hand, introduced the idea of a proper name in a language in which it was applied to what in ordinary life we call “objects”, “things” (“building stones”).

– “What does the word ‘exactness’ mean? Is it real exactness if you are supposed to come to tea at 4.30 and come when a good clock strikes 4.30? Or would it only be exactness if you began to open the door at the moment the clock begins to strike? But how is this moment to be defined and how is “beginning to open the door” to be defined? Would it be correct to say, ‘It is difficult to say what real exactness is, for all we know is only rough approximations’?”)

5). Question and answer: A asks, “How many plates?” B counts them and answers with the numeral.

Systems of communication as for instance 1), 2), 3), 4), 5) we shall call “language-games”. They are more or less akin to what in ordinary language we call games. Children are taught their native language by means of such games, and here they even have the entertaining character of games. We are not, |(Ts-310,8) however, regarding the language-games which we describe as incomplete parts of a language, but as languages complete in themselves, as complete systems of human communication. To keep this point of view in mind, it very often is useful to imagine such a simple language to be the entire system of communication of a tribe in a primitive state of society. Think of primitive arithmetics of such tribes.

When the boy or grown-up learns what one might call special technical languages, e.g., the use of charts and diagrams, descriptive geometry, chemical symbolism, etc., he learns more language-games. (Remark: The picture we have of the language of the grown-up is that of a nebulous mass of language, his mother tongue, surrounded by discreet and more or less clear cut language games, the technical languages.)

6). Asking for the name: we introduce new forms of building stones. B points to one of them & asks, “What is this?”; A answers, “This is a … ”. Later on A calls out this new word, say “arch”, & B brings the stone. The words, “This is a … ” together with the pointing gesture we shall call ostensive explanation or ostensive definition. In case 6) a generic name was explained, in actual fact, the name of a shape. But we can ask analogously for the proper name of a particular object, for the name of a colour, of a number || numeral, of a direction.

(Remark: Our use of expressions like “names of numbers”, “names of colours”, “names of materials”, “names of nations” may spring from two different sources. a) One is that we might imagine the functions of proper names, numerals, words for colours, |(Ts-310,9) etc. to be much more alike than they actually are. If we do so we are tempted to think that the function of every word is more or less like the function of a proper name of a person, or such generic names as “table”, “chair”, “door”, etc. The b) second source is this, that if we see how fundamentally different the functions of such words as “table”, “chair”, etc. are from those of proper names, and how different from either the functions of, say, the names of colours, we see no reason why we shouldn't speak of names of numbers or names of directions either, not by way of saying some such thing as “numbers and directions are just different forms of objects”, but rather by way of stressing the analogy which lies in the lack of analogy between the functions of the words “chair” & “Jack” on the one hand, & “east” and “Jack” on the other hand.)

7). B has a table in which written signs are placed opposite to pictures of objects (say, a table, a chair, a tea-cup, etc.). A writes one of the signs, B looks for it in the table, looks or points with his finger from the written sign to the picture opposite, & fetches the object which the picture represents.

Let us now look at the different kinds of signs which we have introduced. First let us distinguish between sentences and words. A sentence I will call every complete sign in a language-game, its constituent signs are words. (This is merely a rough and general remark about the way I will use the words “proposition” and “word”). A proposition may consist of only one word. In 1) the signs “brick!”, “column!” are the sentences. In 2) a sentence consists of two words. According |(Ts-310,10) to the role which propositions play in a language-game, we distinguish between orders, questions, explanations, descriptions, & so on.

8). If in a language-game similar to 1) A calls out an order: “slab, column, brick!” which is obeyed by B by bringing a slab, a column & a brick, we might here talk of three propositions, or of one only. If on the other hand,

9). the order of words shews B the order in which to bring the building stones, we shall say that A calls out a proposition consisting of three words. If the command in this case took the form, “Slab, then column, then brick!” we should say that it consisted of four words (not of five). Amongst the words we see groups of words with similar functions. We can easily see a similarity in the use of the words “one”, “two”, “three”, etc. & again one in the use of “slab”, “column” & “brick”, etc., & thus we distinguish parts of speech. In 8) all words of the proposition belonged to the same part of speech.

10). The order in which B had to bring the stones in 9) could have been indicated by the use of the ordinals thus: “Second, column; first, slab; third, brick!”. Here we have a case in which what was the function of the order of words in one language-game is the function of particular words in another.

Reflections such as the preceding will shew us the infinite variety of the functions of words in propositions, and it is curious to compare what we see in our examples with the simple & rigid rules which logicians give for the construction of propositions. If we group words together according to the similarity of their functions, thus distinguishing parts of speech, |(Ts-310,11) it is easy to see that many different ways of classification can be adopted. We could indeed easily imagine a reason for not classing the word “one” together with “two”, “three”, etc., as follows:

11). Consider this variation of our language-game 2). Instead of calling out, “One slab!”, “One cube!”, etc., A just calls “slab!”, “cube!”, etc., the use of the other numerals being as described in 2). Suppose that a man accustomed to this form (11)) of communication was introduced to the use of the word “one” as described in 2). We can easily imagine that he would refuse to classify “one” with the numerals “2”, “3”, etc.

(Remark: Think of the reasons for and against classifying “0” with the other cardinals. “Are black and white colours?” In which cases would you be inclined to say so & which not? – Words can in many ways be compared to chess men. Think of the several ways of distinguishing different kind of pieces in the game of chess (e.g., pawns & “officers”).

Remember the phrase, “two or more”.)

It is natural for us to call gestures, as those employed in 4), or pictures as in 7), elements or instruments of language. (We talk sometimes of a language of gestures.) The pictures in 7) & other instruments of language which have a similar function I shall call patterns. (This explanation, as others which we have given, is vague, and meant to be vague.) We may say that words and patterns have different kinds of functions. When we make use of a pattern we compare something with it, e.g., |(Ts-310,12) a chair with the picture of a chair. We did not compare a slab with the word “slab”. In introducing the distinction, “word, pattern”, the idea was not to set up a final logical duality. We have only singled out two characteristic kinds of instruments from the variety of instruments in our language. We shall call “one”, “two”, “three”, etc. words. If instead of these signs we used “–”, “– –”, “– – –”, “– – – –”, we might call these patterns. Suppose in a language the numerals were “one”, “one one”, “one one one”, etc., should we call “one” a word or a pattern? The same element may in one place be used as word & in another as pattern. A circle might be the name for an ellipse, or on the other hand a pattern with which the ellipse is to be compared by a particular method of projection. Consider also these two systems of expression:

12). A gives B an order consisting of two written symbols, the first an irregularly shaped patch of a certain colour, say green, the second the drawn outline of a geometrical figure, say a circle. B brings an object of this outline and that colour, say a circular green object.

13). A gives B an order consisting of one symbol, a geometrical figure painted a particular colour, say a green circle. B brings him a green circular object. In 12) patterns correspond to our names of colours and other patterns to our names of shape. The symbols in 13) cannot be regarded as combinations of two such elements. A word in inverted commas can be called a pattern. Thus in the sentence, “He said, ‘Go to hell’”, ‘Go to hell’ is a pattern of what he said. Compare these cases:

|(Ts-310,13) a) Someone says, “I whistled ![]() (whistling a tune)”; b) Someone writes, “I whistled ”. An onomatopoetic word like “rustling” may be called a pattern. We call a very great variety of processes “comparing an object with a pattern”. We comprise many kinds of symbols under the name “pattern”. In 7) B compares a picture in the table with the objects he has before him. But what does comparing a picture with the object consist in? Suppose the table shewed: a) a picture of a hammer, of pincers, of a saw, of a chisel; b) on the other hand, pictures of twenty different kinds of butterflies. Imagine what the comparison in these cases would consist in, & note the difference. Compare with these cases a third case c) where the pictures in the table represent building stones drawn to scale, & the comparing has to be done with ruler and compasses. Suppose that B's task is to bring a piece of cloth of the colour of the sample. How are the colours of sample and cloth to be compared? Imagine a series of different cases:

(whistling a tune)”; b) Someone writes, “I whistled ”. An onomatopoetic word like “rustling” may be called a pattern. We call a very great variety of processes “comparing an object with a pattern”. We comprise many kinds of symbols under the name “pattern”. In 7) B compares a picture in the table with the objects he has before him. But what does comparing a picture with the object consist in? Suppose the table shewed: a) a picture of a hammer, of pincers, of a saw, of a chisel; b) on the other hand, pictures of twenty different kinds of butterflies. Imagine what the comparison in these cases would consist in, & note the difference. Compare with these cases a third case c) where the pictures in the table represent building stones drawn to scale, & the comparing has to be done with ruler and compasses. Suppose that B's task is to bring a piece of cloth of the colour of the sample. How are the colours of sample and cloth to be compared? Imagine a series of different cases:

14). A shews the sample to B, upon which B goes and fetches the material “from memory”.

15). A gives B the sample, B looks from the sample to the materials on the shelves from which he has to choose.

16). B lays the sample on each bolt of material & chooses that one which he can't distinguish from the sample, for which the difference between the sample & the material seems to vanish.

17). Imagine on the other hand that the order has been, “Bring a material slightly darker than this sample”. In 14) I said that B fetches the material “from memory”, which is using a |(Ts-310,14) common form of expression. But what might happen in such a case of comparing “from memory” is of the greatest variety. Imagine a few instances:

14a). B has a memory image before his mind's eye when he goes for the material. He alternately looks at materials and recalls his image. He goes through this process with, say, five of the bolts, in some instances saying to himself, “Too dark”, in some instances saying to himself, “Too light”. At the fifth bolt he stops, says, “That's it”, & takes it from the shelf.

14b). No memory image is before B's eye. He looks at four bolts, shaking his head each time, feeling some sort of mental tension. On reaching the fifth bolt, this tension relaxes, he nods his head, & takes the bolt down.

14c). B goes to the shelf without a memory image, looks at five bolts one after the other, takes the fifth bolt from the shelf.

“But this can't be all comparing consists in”.

When we call these three preceding cases cases of comparing from memory, we feel that their description is in a sense unsatisfactory, or incomplete. We are inclined to say that the description has left out the essential feature of such a process & given us accessory features only. The essential feature it seems would be what one might call a specific experience of comparing & of recognizing. Now it is queer that on closely looking at cases of comparing, it is very easy to see a great number of activities and states of mind, all more or less characteristic |(Ts-310,15) of the act of comparing. This in fact is so, whether we speak of comparing from memory or of comparing by means of a sample before our eyes. We know a vast number of such processes, processes similar to each other in a vast number of different ways. We hold pieces whose colours we want to compare together or near each other for a longer or shorter period, look at them alternately or simultaneously, place them under different lights, say different things while we do so, have memory images, feelings of tension & relaxation, satisfaction & dissatisfaction, the various feelings of strain in and around our eyes accompanying prolonged gazing at the same object, & all possible combinations of these & many other experiences. The more such cases we observe & the closer we look at them, the more doubtful we feel about finding one particular mental experience characteristic of comparing. In fact, if after you had scrutinized a number of such closely, I admitted that there existed a peculiar mental experience which you might call the experience of comparing, & that if you insisted, I should be willing to adopt the word “comparing” only for cases in which this peculiar feeling had occurred, you would now feel that the assumption of such a peculiar experience had lost its point, because this experience was placed side by side with a vast number of other experiences which after we have scrutinized the cases seems to be that which really constitutes what connects all the cases of comparing. For the “specific experience” we had been looking for was meant to have played the role which has been assumed by the mass of experiences revealed to us by our |(Ts-310,16) scrutiny: We never wanted the specific experience to be just one among a number of more or less characteristic experiences. (One might say that there are two ways of looking at this matter, one as it were, at close quarters, the other as though from a distance and through the medium of a peculiar atmosphere.) In fact we have found that the use which we really make of the word “comparing” is different from that which looking at it from far away we were led to expect. We find that what connects all the cases of comparing is a vast number of overlapping similarities, and as soon as we see this, we feel no longer compelled to say that there must be some one feature common to them all. What ties the ship to the wharf is a rope, and the rope consists of fibres, but it does not get its strength from any fibre which runs through it from one end to the other, but from the fact that there is a vast number of fibres overlapping.

“But surely in case 14c) B acted entirely automatically. If all that happened was really what was described there, he did not know why he chose the bolt he did choose. He had no reason for choosing it. If he chose the right one, he did it as a machine might have done it”. Our first answer is that we did not deny that B in case 14c) had what we should call a personal experience, for we did not say that he didn't see the materials from which he chose or that which he chose, nor that he didn't have muscular and tactile sensations and such like while he did it. Now what would such a reason which justified his choice and made it non-automatic be like? (i.e.: What do we |(Ts-310,17) imagine it to be like?) I suppose we should say that the opposite of automatic comparing, as it were, the ideal case of conscious comparing, was that of having a clear memory image before our mind's eye or of seeing a real sample & of having a specific feeling of not being able to distinguish in a particular way between these samples and the material chosen. I suppose that this peculiar sensation is the reason, the justification, for the choice. This specific feeling, one might say, connects the two experiences of seeing the sample, on the one hand, and the material on the other. But if so, what connects this specific experience with either? We don't deny that such an experience might intervene. But looking at it as we did just now, the distinction between automatic and non-automatic appears no longer clear-cut and final as it did at first. We don't mean that this distinction loses its practical value in particular cases, e.g., if asked under particular circumstances, “Did you take this bolt from the shelf automatically, or did you think about it?”, we may be justified in saying that we did not act automatically and give as a reason || explanation we had looked at the material carefully, had tried to recall the memory image of the pattern, & had uttered to ourselves doubts and decisions. This may in the particular case be taken to distinguish automatic from non-automatic. In another case however we may distinguish between an automatic & a non-automatic way of the appearance of a memory image, and so on.

If our case 14c) troubles you, you may be inclined to say: “But why did he bring just this bolt of material? How has he |(Ts-310,18) recognized it as the right one? What by? – If you ask “why”, do you ask for the cause or for the reason? If for the cause, it is easy enough to think up a physiological or psychological hypothesis which explains this choice under the given conditions. It is the task of the experimental sciences to test such hypotheses. If on the other hand you ask for a reason the answer is, “There need not have been a reason for the choice. A reason is a step preceding the step of the choice. But why should every step be preceded by another one?”

“But then B didn't really recognize the material as the right one”. – You needn't reckon 14c) among the cases of recognizing, but if you have become aware of the fact that the processes which we call processes of recognition form a vast family with overlapping similarities, you will probably feel not disinclined to include 14c) in this family, too. – “But doesn't B in this case lack the criterion by which he can recognize the material? In 14a), e.g., he had the memory image and he recognized the material he looked for by its agreement with the image”. – But had he also a picture of this agreement before him, a picture with which he could compare the agreement between the pattern and the bolt to see whether it was the right one? And, on the other hand, couldn't he have been given such a picture? Suppose, e.g., that A wished B to remember that what was wanted was a bolt exactly like the sample, not, as perhaps in other cases, a material slightly darker than the pattern. Couldn't A in this case have given to B an example of the agreement required by giving him two pieces of the same colour (e.g., |(Ts-310,19) as a kind of reminder)? Is any such link between the order & its execution necessarily the last one? – And if you say that in 14b) at least he had the relaxing of the tension by which to recognize the right material, had he to have an image of this relaxation about him to recognize it as that by which the right material was to be recognized? ‒ ‒

“But supposing B brings the bolt, as in 14c), & on comparing it with the pattern it turns out to be the wrong one?” – But couldn't that have happened in all the other cases as well? Suppose in 14a) the bolt which B brought back was found not to match with the pattern. Wouldn't we in some such cases say that his memory image had changed, in others that the pattern or the material had changed, in others again that the light had changed? It is not difficult to invent cases, imagine circumstances, in which each of these judgements would be made. – “But isn't there after all an essential difference between the cases 14a) & 14c)?”‒ ‒ Certainly! Just that pointed out in the description of these cases. ‒ ‒

In 1) B learnt to bring a building stone on hearing the word “column!” called out. We could imagine what happened in such a case to be this: In B's mind the word called out brought up an image of a column, say; the training had, as we should say, established this association. B takes up that building stone which conforms to his image. – But was this necessarily what happened? If the training could bring it about that the idea or image – automatically – arose in B's mind, why shouldn't it bring about B's actions without the intervention of an image?

|(Ts-310,20) This would only come to a slight variation of the associative mechanism. Bear in mind that the image which is brought up by the word is not arrived at by a rational process (but if it is, this only pushes our argument further back), but that this case is strictly comparable with that of a mechanism in which a button is pressed and an indicator plate appears. In fact this sort of mechanism can be used instead of that of association.

Mental images of colours, shapes, sounds, etc. etc., which play a role in communication by means of language we put in the same category with patches of colour actually seen, sounds heard.

18). The object of the training in the use of tables (as in 7)) may be not only to teach the use of one particular table, but it may be to enable the pupil to use or construct himself tables with new coordinations of written signs & pictures. Suppose the first table a person was trained to use contained the four words “hammer”, “pincers”, “saw”, “chisel” & the corresponding pictures. We might now add the picture of another object which the pupil had before him, say of a plane, & correlate with it the word “plane”. We shall make the correlation between this new picture and word as similar as possible to the correlations in the previous table. Thus we might add the new word and picture on the same sheet, and place the new word under the previous words and the new picture under the previous pictures. The pupil will now be encouraged to make use of the new picture and word without the special training which we gave him when we taught him to use the first table.

|(Ts-310,21) These acts of encouragement will be of various kinds, and many such acts will only be possible if the pupil responds, and responds in a particular way. Imagine the gestures, sounds, etc. of encouragement you use when you teach a dog to retrieve. Imagine on the other hand, that you tried to teach a cat to retrieve. As the cat will not respond to your encouragement, most of the acts of encouragement which you performed when you trained the dog are here out of the question.

19). The pupil could also be trained to give things names of his own invention and to bring the objects when the names are called. He is, e.g., presented with a table on which he finds pictures of objects around him on one side and blank spaces on the other, and he plays the game by writing signs of his own invention opposite the pictures and reacting in the previous way when these signs are used as orders. Or else,

20). the game may consist in B's constructing a table and obeying orders given in terms of this table. When the use of a table is taught, and the table consists, say, of two vertical columns, the left hand one containing the names, the right hand one the pictures, a name and a picture being correlated by standing on a horizontal line, an important feature of the training may be that which makes the pupil slide his finger from left to right, as it were the training to draw a series of horizontal lines, one below the other. Such training may help to make the transition from the first table to the new item.

Tables, ostensive definitions, & similar instruments I shall call rules, in accordance with ordinary usage. The use of a rule can be explained by a further rule.

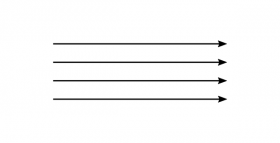

|(Ts-310,22) 21). Consider this example: We introduce different ways of reading tables. Each table consists of two columns of words & pictures, as above. In some cases they are to be read horizontally from left to right, i.e., according to the scheme:

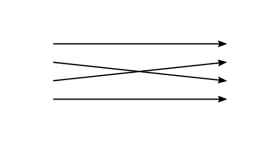

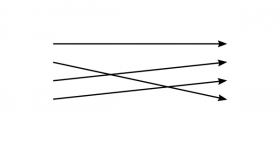

In others according to such schemes as:

Or:

etc.

Schemes of this kind can be adjoined to our tables, as rules for reading them. Could not these rules again be explained by further rules? Certainly. On the other hand, is a rule incompletely explained if no rule for its usage has been given?

We introduce into our language-games the endless series of numerals. But how is this done? Obviously the analogy between this process & that of introducing a series of twenty numerals is not the same as that between introducing a series of twenty numerals and introducing a series of ten numerals. Suppose that our game was like 2) but played with the endless series of numerals. The difference between it & 2) would not be just that more numerals were used. That is to say, suppose that as a matter of fact in playing the game we had actually made use of, say, 155 numerals, the game we play would not be that which could be described by saying that we played the game 2), only with 155 instead of 10 numerals. But what does the difference consist in? (The difference would seem to be almost |(Ts-310,23) one of the spirit in which the games are played.) The difference between games can lie say in the number of the counters used, in the number of squares of the playing board, or in the fact that we use squares in one case & hexagons in the other, & such like. Now the difference between the finite and infinite game does not seem to lie in the material tools of the game; for we should be inclined to say that infinity can't be expressed in them, that is, that we can only conceive of it in our thoughts & hence that it is in these thoughts that the finite and infinite game must be distinguished. (It is queer though that these thoughts should be capable of being expressed in signs.) Let us consider two games. They are both played with cards carrying numbers, and the highest number takes the trick.

22). One game is played with a fixed number of such cards, say 32. In the other game we are under certain circumstances allowed to increase the number of cards to as many as we like, by cutting pieces of paper and writing numbers on them. We will call the first of these games bounded, the second unbounded. Suppose a hand of the second game was played & the number of cards actually used was 32. What is the difference in this case between playing a hand a) of the unbounded game & playing a hand b) of the bounded game?

The difference will not be that between a hand of a bounded game with 32 cards and a hand of a bounded game with a greater number of cards. The number of cards used was, we said, the same. But there will be differences of another kind, e.g., the bounded game is played with a normal pack of cards, the unbounded game with a large supply of blank cards & pencils.

|(Ts-310,24) The unbounded game is opened with the question, “How high shall we go?” If the players look up the rules of this game in a book of rules, they will find the phrase “& so on” or “& so on ad inf.” at the end of certain series of rules. So the difference between the two hands a) & b) lies in the tools we use, though admittedly not in the cards they are played with. But this difference seems trivial and not the essential difference between the games. We feel that there must be a big & essential difference somewhere. But if you look closely at what happens when the hands are played, you find that you can only detect a number of differences in details, each of which would seem inessential. The acts, e.g., of dealing & playing the cards may in both cases be identical. In the course of playing the hand a), the players may have considered making up more cards, & again discarded the idea. But what was it like to consider this? It could be some such process as saying to themselves or aloud, “I wonder whether I should make up another card”. Again, no such consideration may have entered the minds of the players. It is possible that the whole difference in the events of a hand of the bounded, and a hand of the unbounded game lay in what was said before the game started, e.g., “Let's play the bounded game”.

“But isn't it correct to say that hands of the two different games belong to two different systems?” Certainly. Only the facts which we are referring to by saying that they belong to different systems are much more complex than we might expect them to be.

Let us now compare language-games of which we should say |(Ts-310,25) that they are played with a limited set of numerals with language-games of which we should say that they are played with the endless series of numerals.

23). Like 2) A orders B to bring him a number of building stones. The numerals are the signs “1”, “2”, etc. … “9”, each written on a card. A has a set of these cards and gives B the order by shewing him one of the set & calling out one of the words, “slab”, “column”, etc.

24). Like 23), only there is no set of indexed cards. The series of numerals 1 … 9 is learned by heart. The numerals are called out in the orders, & the child learns them by word of mouth.

25). An abacus is used. A sets the abacus, gives it to B, B goes with it to where the slabs lie, etc.

26). B is to count the slabs in a heap. He does it with an abacus, the abacus has twenty beads. There are never more than 20 plates in a heap. B sets the abacus for the heap in question & shews A the abacus thus set.

27). Like 26). The abacus has 20 small beads & one large one. If the heap contains more than 20 plates, the large bead is moved. (So the large bead in some way corresponds to the word “many”).

28). Like 26). If the heap contains n plates, n being more than 20 but less than 40, B moves n-20 beads, shews A the abacus thus set, & claps his hand once.

29). A & B use the numerals of the decimal system (written or spoken) up to 20. The child learning this language learns these |(Ts-310,26) numerals by heart, etc., as in 2).

30). A certain tribe has a language of the kind 2). The numerals used are those of our decimal system. No one numeral used can be observed to play the predominant role of the last numeral in some of the above games (27), 28)). (One is tempted to continue this sentence by saying, “although there is of course a highest numeral actually used”). The children of the tribe learn the numerals in this way: They are taught the signs from 1 to 20 as in 2) and to count rows of beads of no more than 20 on being ordered, “Count these”. When in counting the pupil arrives at the numeral 20, one makes a gesture suggestive of “Go on”, upon which the child says (in most cases at any rate) “21”. Analogously, the children are made to count to 22 & to higher numbers, no particular number playing in these exercises the predominant role of a last one. The last stage of the training is that the child is ordered to count a group of objects, well above 20, without the suggestive gesture being used to help the child over the numeral 20. If a child does not respond to the suggestive gesture, it is separated from the others and treated as a lunatic.

31). Another tribe. Its language is like that in 30). The highest numeral observed in use is 159. In the life of this tribe the numeral 159 plays a peculiar role. Supposing I said, “They treat this number as their highest”, – but what does this mean? Could we answer: “They just say that it is the highest”? – They say certain words, but how do we know what they mean by them? A criterion for what they mean would be the occasions |(Ts-310,27) on which the word we are inclined to translate into our word “highest” is used, the role, we might say, which we observe this word to play in the life of the tribe. In fact we could easily imagine the numeral 159 to be used on such occasions, in connection with such gestures and forms of behaviour as would make us say that this numeral plays the role of an unsurmountable limit, even if the tribe had no word corresponding to our “highest”, and the criteria for numeral 159 being the highest numeral did not consist of anything that was said about the numeral.

32). A tribe has two systems of counting. People learned to count with the alphabet from A to Z and also with the decimal system as in 30). If a man is to count objects with the first system, he is ordered to count “in the closed way”, in the second case, “in the open way”; & the tribe uses the words “closed” & “open” also for a closed and open door.

(Remarks: 23) is limited in an obvious way by the set of cards. 24): Note analogy and lack of analogy between the limited supply of cards in 23) & of words in our memory in 24). Observe that the limitation in 26) on the one hand lies in the tool (the abacus of 20 beads) & its usage in our game, on the other hand (in a totally different way) in the fact that in the actual practice of playing the game no more than 20 objects are ever to be counted. In 27) that latter kind of limitation was absent, but the large bead rather stressed the limitation of our means. Is 28) a limited or an unlimited game? The practice we have described gives the limit 40. We are inclined to say this game “has it in it” to be continued indefinitely, but remember |(Ts-310,28) that we could also have construed the preceding games as beginnings of a system. In 29) the systematic aspect of the numerals used is even more conspicuous than in 28). One might say that there was no limitation imposed by the tools of this game, if it were not for the remark that the numerals up to 20 are learnt by heart. This suggests the idea that the child is not taught to “understand” the system which we see in the decimal notation. Of the tribe in 30) we should certainly say that they are trained to construct numerals indefinitely, that the arithmetic of their language is not a finite one, that their series of numbers has no end. (It is just in such a case when numerals are constructed “indefinitely” that we say that people have the infinite series of numbers.) 31) might shew you what a vast variety of cases can be imagined in which we should be inclined to say that the arithmetic of the tribe deals with a finite series of numbers, even in spite of the fact that the way in which the children are trained in the use of numerals suggests no upper limit. In 32) the terms “closed” & “open” (which could by a slight variation of the example be replaced by “limited” and “unlimited”) are introduced into the language of the tribe itself. Introduced in that simple and clearly circumscribed game, there is of course nothing mysterious about the use of the word “open”. But this word corresponds to our “infinite”, & the games we play with the latter differ from 31) only by being vastly more complicated. In other words, our use of the word “infinite” is just as straight forward as that of “open” in 31 || 32?), and our idea that its meaning is |(Ts-310,29) “transcendent” rests on a misunderstanding.)

We might say roughly that the unlimited cases are characterized by this: that they are not played with a definite supply of numerals, but instead with a system for constructing numerals (indefinitely). When we say that someone has been supplied with a system for constructing numerals, we generally think of either of three things: a) of giving him a training similar to that described in 30), which, experience teaches us, will make him pass tests of the kind mentioned there; b) of creating a disposition in the same man's mind, or brain, to react in that way; c) of supplying him with a general rule for the construction of numerals.

What do we call a rule? Consider this example:

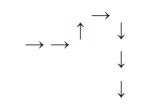

33). B moves about according to rules which A gives him. B is supplied with the following table:

| a | → |

| b | ← |

| c | ↑ |

| d | ↓ |

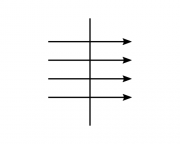

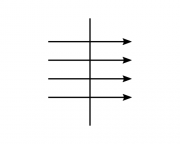

A gives an order made up of the letters in the table, say: “a a c a d d d”. B looks up the arrow corresponding to each letter of the order and moves accordingly; in our example thus:

The table 33) we should call a rule (or else “the expression of a rule”. Why I give these synonymous expressions will appear later.) We shan't be inclined to call the sentence “a a c a d d d” itself a rule. It is of course the description of the way B has to take. On the other hand, such a description would under certain circumstances be called a rule, e.g., in the following case:

|(Ts-310,30) 34). B is to draw various ornamental linear designs. Each design is a repetition of one element which A gives him. Thus if A gives the order “c a d a”, B draws a line thus: ![]()

In this case I think we should say that “c a d a” is the rule for drawing the design. Roughly speaking, it characterizes what we call a rule to be applied repeatedly, in an indefinite number of instances. Cf., e.g., the following case with 34):

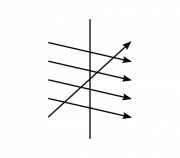

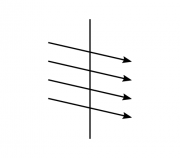

35). A game played with pieces of various shapes on a chess board. The way each piece is allowed to move is laid down by a rule. Thus the rule for a particular piece is “ac”, for another piece “acaa”, & so on. The first piece then can make a move like this: ![]() , the second, like this:

, the second, like this: ![]() . Both a formula like “ac” or a diagram like that corresponding to such a formula might here be called a rule.

. Both a formula like “ac” or a diagram like that corresponding to such a formula might here be called a rule.

36). Suppose that after playing the game 33) several times as described above, it was played with this variation: that B no longer looked at the table, but reading A's order the letters call up the images of the arrows (by association), & B acts according to these imagined arrows.

37). After playing it like this for several times, B moves about according to the written order as he would have done had he looked up or imagined the arrows, but actually without any such picture intervening. Imagine even this variation:

38). B in being trained to follow a written order, is shewn the table of 33) once, upon which he obeys A's orders without further intervention of the table in the same way in which B in |(Ts-310,31) 33) does with the help of the table on each occasion.

In each of these cases, we might say that the table 33) is a rule of the game. But in each one this rule plays a different role. In 33) the table is an instrument used in what we should call the practice of the game. It is replaced in 36) by the working of association. In 37) even this shadow of the table has dropped out of the practice of the game, and in 38) the table is admittedly an instrument for the training of B only.

But imagine this further case:

39). A certain system of communication is used by a tribe. I will describe it by saying that it is similar to our game 38) except that no table is used in the training. The training might have consisted in several times leading the pupil by the hand along the path one wanted him to go. But we could also imagine a case:

40). where even this training is not necessary, where, as we should say, the look of the letters abcd naturally produced an urge to move in the way described. This cause at first sight looks puzzling. We seem to be assuming a most unusual working of the mind. Or we may ask || perhaps we ask, “How on earth is he to know which way to move if the letter a is shewn him”? But isn't B's reaction in this case the very reaction described in 37) & 38), & in fact our usual reaction when for instance we hear and obey an order? For, the fact that the training in 38) & 39) preceded the carrying out of the order does not change the process of carrying out. In other words the “curious mental mechanism” assumed in 40) is no other than that which we assumed to be |(Ts-310,32) created by the training in 37) and 38). “But could such a mechanism be born with you?” But did you find any difficulty in assuming that that mechanism was born with B, which enabled him to respond to the training in the way he did? And remember that the rule or explanation given in table 33) of the signs abcd was not essentially the last one, and that we might have given a table for the use of such tables, and so on. (Cf. 21)).

How does one explain to a man how he should carry out the order, “Go this way!” (pointing with an arrow the way he should go)? Couldn't this mean going the direction which we should call the opposite of that of the arrow? Isn't every explanation of how he should follow the arrow in the position of another arrow? What would you say to this explanation: A man says, “If I point this way (pointing with his right hand) I mean you to go like this” (pointing with his left hand the same way)? This just shews you the extremes between which the uses of signs vary.

Let us return to 39). Someone visits the tribe and observes the use of the signs in their language. He describes the language by saying that its sentences consist of the letters abcd used according to the table: (of 33)). We see that the expression, “A game is played according to the rule so-and-so” is used not only in the variety of cases exemplified by 36), 37), & 38), but even in cases where the rule is neither an instrument of the training nor of the practice of the game, but stands in the relation to it in which our table stands to the practice of our game 39). One might in this case call the table a natural |(Ts-310,33) law describing the behaviour of the people of this tribe. Or we might say that the table is a record belonging to the natural history of the tribe.

Note that in the game 33) I distinguished sharply between the order to be carried out and the rule employed. In 34) on the other hand, we called the sentence “c a d a” a rule, & it was the order. Imagine also this variation:

41). The game is similar to 33), but the pupil is not just trained to use a single table; but the training aims at making the pupil use any table correlating letters with arrows. Now by this I mean no more than that the training is of a peculiar kind, roughly speaking one analogous to that described in 30). I will refer to a training more or less similar to that in 30) as a “general training”. General trainings form a family whose members differ greatly from one another. The kind of thing I'm thinking of now mainly consists: a) of a training in a limited range of actions, b) of giving the pupil a lead to extend this range, & c) of random exercises and tests. After the general training the order is now to consist in giving him a sign of this kind:

rrtst

| r | ↗ |

| s | ↖ |

| t | ↓ |

He carries out the order by moving thus:

Here I suppose we should say the table, the rule, is part of the order.

Note, we are not saying “what a rule is” but just giving different applications of the word “rule”; & we certainly do this by giving applications of the words “expression of a rule”.

Note also that in 41) there is no clear case against calling |(Ts-310,34) the whole symbol given the sentence, though we might distinguish in it between the sentence and the table. What in this case more particularly tempts us to this distinction is the linear writing of the part outside the table. Though from certain points of view we should call the linear character of the sentence merely external and inessential, this character and similar ones play a great role in what as logicians we are inclined to say about sentences and propositions. And therefore if we conceive of the symbol in 41) as a unit, this may make us realise what a sentence can look like.

Let us now consider these two games:

42). A gives orders to B: they are written signs consisting of dots and dashes and B executes them by doing a figure in dancing with a particular step. Thus the order “– ·” is to be carried out by taking a step and a hop alternately; the order “· · – – –” by alternately taking two hops and three steps, etc. The training in this game is “general” in the sense explained in 41); and I should like to say, “the orders given don't move in a limited range. They comprise combinations of any number of dots and dashes”. – But what does it mean to say that the orders don't move in a limited range? Isn't this nonsense? Whatever orders are given in the practice of the game constitute the limited range. – Well, what I meant to say by “the orders don't move in a limited range” was that neither in the teaching of the game nor in the practice of it a limitation of the range plays a “predominant” role (see 30)) or, as we might say, the range of the game (it is superfluous to say |(Ts-310,35) limited) is just the extent of its actual (“accidental”) practice. (Our game is in this way like 30)) Cf. with this game the following:

43). The orders and their execution as in 42); but only these three signs are used: “– ·”, “– · ·”, “· – –”. We say that in 42) B in executing the order is guided by the sign given to him. But if we ask ourselves whether the three signs in 43) guide B in executing the orders, it seems that we can say both yes and no according to the way we look at the execution of the orders.

If we try to decide whether B in 43) is guided by the signs or not, we are inclined to give such answers as the following: a) B is guided if he doesn't just look at an order, say “· – –” as a whole and then act, but if he reads it “word by word” (the words used in our language being “·” “–”) and acts according to the words he has read.

We could make these cases clearer if we imagine that the “reading word by word” consisted in pointing to each word of the sentence in turn with one's finger as opposed to pointing at the whole sentence at once, say by pointing to the beginning of the sentence. And the “acting according to the words” we shall for the sake of simplicity imagine to consist in acting (stepping or hopping) after each word of the sentence in turn. – b) B is guided if he goes through a conscious process which makes a connection between the pointing to a word and the act of hopping and stepping. Such a connection could be imagined in many different ways. E.g., B has a table in which a dash |(Ts-310,36) is correlated to the picture of a man making a step and a dot to a picture of a man hopping. Then the conscious acts connecting reading the order and carrying it out might consist in consulting the table, or in consulting a memory image of it “with one's mind's eye”. c) B is guided if he does not just react to looking at each word of the order, but experiences the peculiar strain of “trying to remember what the sign means”, & further, the relaxing of this strain when the meaning, the right action, comes before his mind.

All these explanations seem in a peculiar way unsatisfactory, and it is the limitation of our game which makes them unsatisfactory. This is expressed by the explanation that B is guided by the particular combination of words in one of our three sentences if he could also have carried out orders consisting in other combinations of dots and dashes. And if we say this, it seems to us that the “ability” to carry out other orders is a particular state of the person carrying out the orders of 42). And at the same time we can't in this case find anything which we should call such a state.

Let us see what role the words “can” or “to be able to” play in our language. Consider these examples:

44). Imagine that for some purpose or other people use a kind of instrument or tool; this consists of a board with a slot in it guiding the movement of a peg. The man using the tool slides the peg along the slot. There are such boards with straight slots, circular slots, elliptic slots, etc. The language of the people using this instrument has expressions for |(Ts-310,37) describing the activity of moving the peg in the slot. They talk of moving it in a circle, in a straight line, etc. They also have a means of describing the board used. They do it in this form: “This is a board in which the peg can be moved in a circle”. One could in this case call the word “can” an operator by means of which the form of expression describing an action is transformed into a description of the instrument.

45). Imagine a people in whose language there is no such form of sentence as “the book is in the drawer” or “water is in the glass”, but wherever we should use these forms they say, “The book can be taken out of the drawer”, “The water can be taken out of the glass”.

46). An activity of the men of a certain tribe is to test sticks as to their hardness. They do it by trying to bend the sticks with their hands. In their language they have expressions of the form, “This stick can be bent easily” or “This stick can be bent with difficulty”. They use these expressions as we use “This stick is soft” or “This stick is hard”. I mean to say that they don't use the expression, “This stick can be bent easily” as we should use the sentence “I am bending the stick with ease”. Rather they use their expression in a way which would make us say that they are describing a state of the stick. I.e., they use such sentences as, “This hut is built of sticks that can be bent easily”. (Think of the way in which we form adjectives out of verbs by means of the ending “-able”, e.g., “deformable”.)

Now we might say that in the last three cases the sentences |(Ts-310,38) of the form “so-and-so can happen” described the state of objects, but there are great differences between these examples. In 44) we saw the state described before our eyes. We saw that the board had a circular or a straight slot, etc. In 45), in some instances at least this was the case, we could see the objects in the box, the water in the glass, etc. In such cases we use the expression “state of an object” in such a way that there corresponds to it what one might call a stationary sense experience.

When on the other hand, we talk of the state of a stick in 46), observe that to this “state” there does not correspond a particular sense experience which lasts while the state lasts. Instead of that, the defining criterion for something being in this state consists in certain tests.

We may say that a car travels 20 miles an hour even if it only travels for half an hour. We can explain our form of expression by saying that the car travels with a speed which enables it to make 20 miles an hour. And here also we are inclined to talk of the velocity of the car as of a state of its motion. I think we should not use this expression if we had no other “experiences of motion” than those of a body being in a particular place at a certain time and in another place at another time; if, e.g., our experiences of motion were of the kind which we have when we see the hour hand of the clock has moved from one point of the dial to the other.

47). A tribe has in its language commands for the execution of certain actions of men in warfare, something like “Shoot!”, |(Ts-310,39) “Run!”, “Crawl!”, etc. They also have a way of describing a man's build. Such a description has the form “He can run fast”, “He can throw the spear far”. What justifies me in saying that these sentences are descriptions of the man's build is the use which they make of sentences of this form. Thus if they see a man with bulging leg muscles but who as we should say has not the use of his legs for some reason or other, they say he is a man who can run fast. The drawn image of a man which shews large biceps they describe as representing a man “who can throw a spear far”.

48). The men of a tribe are subjected to a kind of medical examination before going into war. The examiner puts the men through a set of standardised tests. He lets them lift certain weights, swing their arms, skip, etc. The examiner then gives his verdict in the form “So-and-so can throw a spear” or “can throw a boomerang” or “is fit to pursue the enemy”, etc. There are no special expressions in the language of this tribe for the activities performed in the tests; but these are referred to only as the tests for certain activities in warfare.

It is an important remark concerning this example and others which we give that one may object to the description which we give of the language of a tribe, that in the specimens we give of their language we let them speak English, thereby already presupposing the whole background of the English language, that is, our usual meanings of the words. Thus if I say that in a certain language there is no special verb for “skipping”, but that this language uses instead the form “making |(Ts-310,40) the test for throwing the boomerang”, one may ask how I have characterized the use of the expressions, “make a test for” & “throwing the boomerang”, to be justified in substituting these English expressions for whatever their actual words may be. To this we must answer that we have only given a very sketchy description of the practices of our fictitious languages, in some cases only hints, but that one can easily make these descriptions more complete. Thus in 48) I could have said that the examiner uses orders for making the men go through the tests. These orders all begin with one particular expression which I could translate into the English words, “Go through the test”. And this expression is followed by one which in actual warfare is used for certain actions. Thus there is a command upon which men throw their boomerangs and which therefore I should translate into, “Throw the boomerangs”. Further, if a man gives an account of the battle to his chief, he again uses the expression I have translated into “Throw a boomerang”, this time in a description. Now what characterizes an order as such or a description as such or a question as such, etc., is – as we have said – the role which the utterance of these signs plays in the whole practice of the language. That is to say, whether a word of the language of our tribe is rightly translated into a word of the English language depends upon the role this word plays in the whole life of the tribe; the occasions on which it is used, the expressions of emotions by which it is generally accompanied, the ideas which it generally awakens or which prompt its saying, etc. etc. As an exercise ask yourself: in which |(Ts-310,41) cases would you say that a certain word uttered by the people of the tribe was a greeting? In which cases should we say it corresponded to our “Goodbye”, in which to our “Hello”? In which cases would you say that a word of a foreign language corresponded to our “perhaps”? – to our expressions of doubt, trust, certainty? You will find that the justifications for calling something an expression of doubt, conviction, etc. largely, though of course not wholly, consist in descriptions of gestures, the play of facial expressions, and even the tone of voice. Remember at this point that the personal experiences of an emotion must in part be strictly localized experiences; for if I frown in anger I feel the muscular tension of the frown in my forehead, & if I weep, the sensations around my eyes are obviously part, and an important part, of what I feel. This is, I think, what William James meant when he said that a man doesn't cry because he is sad but that he is sad because he cries. The reason why this point is often not understood is that we think of the utterance of an emotion as though it were some artificial device to let others know that we have it. Now there is no sharp line between such “artificial devices” and what one might call the natural expressions of emotion. Cf. in this respect: a) weeping, b) raising one's voice when one is angry, c) writing an angry letter, d) ringing the bell for a servant you wish to scold.

49). Imagine a tribe in whose language there is an expression corresponding to our “He has done so-and-so” and another expression corresponding to our “He can do so-and-so”, this latter |(Ts-310,42) expression, however, being only used where its use is justified by the same fact which would also justify the former expression. Now what can make me say this? They have a form of communication which we should call narration of past events because of the circumstances under which it is employed. There are also circumstances under which we should ask and answer such questions as “Can so-and-so do this?”. Such circumstances can be described, e.g., by saying that a chief picks men suitable for a certain action, say crossing a river, climbing a mountain, etc. As the defining criteria of “the chief picking men suitable for this action”, I will not take what he says but only the other features of the situation. The chief under these circumstances asks a question which, as far as its practical consequences go, would have to be translated by our “Can so-and-so swim across this river?” This question, however, is only answered affirmatively by those who actually have swum across this river. This answer is not given in the same words in which under the circumstances characterizing narration he would say that he has swum across this river, but it is given in the terms of the question asked by the chief. On the other hand, this answer is not given in cases in which we should certainly give the answer, “I can swim across this river”, if, e.g., I had performed more difficult feats of swimming though not just that of swimming across this particular river.

By the way, have the two phrases, “He has done so-&-so” and “He can do so-&-so” the same meaning in this language or have they different meanings? If you think about it, something |(Ts-310,43) will tempt you to say the one, something to say the other. This only shows that the question has here no clearly defined meaning. All I can say is: If the fact that they only say, “He can … ” if he has done … is your criterion for the same meaning, then the two expressions have the same meaning. If the circumstances under which an expression is used make its meaning, the meanings are different. The use which is made of the word “can” – the expression of possibility in 49) – can throw a light upon the idea that what can happen must have happened before (Nietzsche). It will also be interesting to look, in the light of our examples, on the statement that what happens can happen.

Before we go on with our consideration of the use of “the expression of possibility”, let us get clearer about that department of our language in which things are said about past & future, that is, about the use of sentences containing such expressions as “yesterday”, “a year ago”, “in five minutes”, “before I did this”, etc. Consider this example: