Project:The copyright status of Wittgenstein’s works: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{header|print=1}} | {{header|print=1}} | ||

{{p center|By {{person link|Michele Lavazza}}<ref group="N">The author would like to thank Dr Jasmin Trächtler, Mr David Chandler, and Mr Javier Arango for reviewing this text.</ref>}} | {{p center|By {{person link|Michele Lavazza}}<ref group="N">The author would like to thank Dr Jasmin Trächtler, Mr David Chandler, and Mr Javier Arango for reviewing this text. Additionally, he would like to extend sincere gratitude to Dr Nicolas Bell, the Librarian of Trinity College, who provided insightful comments on a draft of this essay.</ref>}} | ||

{{p center|31 July 2022}} | {{p center|31 July 2022}} | ||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

Regardless of the agreements that copyright holders and publishers may have, however, the expiry of the copyright term is always a sufficient condition for the work to be in the public domain. No contract has the power to extend copyright protection beyond the term defined by the local legislation. | Regardless of the agreements that copyright holders and publishers may have, however, the expiry of the copyright term is always a sufficient condition for the work to be in the public domain. No contract has the power to extend copyright protection beyond the term defined by the local legislation. | ||

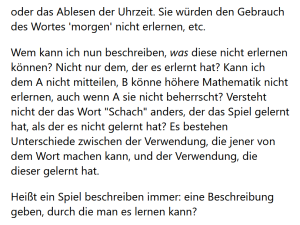

[[File:Example_of_abusive_copyrighting.jpg|thumb|left|Example of an unwarranted and abusive apposition of the “©” sign on the back of a postcard sold by a museum. The postcard features a faithful reproduction of ''{{plainlink|[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gustave_Moreau_Salom%C3%A9_1876.jpg Salomé dansant]}}'', a painting by Gustave Moreau (1826–1898). The painting is in the public domain everywhere in the world, and the photograph does not meet the requirements | [[File:Example_of_abusive_copyrighting.jpg|thumb|left|Example of an unwarranted and abusive apposition of the “©” sign on the back of a postcard sold by a museum. The postcard features a faithful reproduction of ''{{plainlink|[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gustave_Moreau_Salom%C3%A9_1876.jpg Salomé dansant]}}'', a painting by Gustave Moreau (1826–1898). The painting is in the public domain everywhere in the world, and the photograph is not eligible for copyright protection because it does not meet the requirements in terms of originality.]] | ||

This, as well as the general nature of the public domain itself, is sometimes the subject of misunderstandings because publishers tend to print the copyright symbol “©” or another copyright notice on all books they produce, regardless of the copyright status of the text, possibly hoping to protect the typesetting and layout (which, however, are usually below the {{plainlink|[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Threshold_of_originality threshold of originality]}}) or perhaps simply trying to discourage photocopying even public domain texts. As mentioned above ([[#Introduction. The purpose of copyright and the public domain|§ Introduction. The purpose of copyright and the public domain]]), however, adding copyright symbols where they do not belong should be regarded as illegal. | This, as well as the general nature of the public domain itself, is sometimes the subject of misunderstandings because publishers tend to print the copyright symbol “©” or another copyright notice on all books they produce, regardless of the copyright status of the text, possibly hoping to protect the typesetting and layout (which, however, are usually below the {{plainlink|[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Threshold_of_originality threshold of originality]}})<ref>It may be worth noting, incidentally, that some countries do have “typographical copyrigh”, i.e., laws that specifically protect typesetting and layout. The UK is one such country: see Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, section 15.</ref> or perhaps simply trying to discourage photocopying even public domain texts. As mentioned above ([[#Introduction. The purpose of copyright and the public domain|§ Introduction. The purpose of copyright and the public domain]]), however, adding copyright symbols where they do not belong should be regarded as illegal. | ||

Additional restrictions may make the picture more complicated. | Additional restrictions may make the picture more complicated. | ||

| Line 207: | Line 207: | ||

Their country of origin is the US.<ref name="simultaneous">According to the Berne Convention, “The country of origin shall be considered to be: (a) in the case of works first published in a country of the Union, that country; in the case of works published simultaneously in several countries of the Union which grant different terms of protection, the country whose legislation grants the shortest term of protection [...]” (art. 5, par. 4). The definition of “simultaneous publication” is publication in multiple countries within 30 days (see art. 3, par. 4). We haven’t been able to prove that in the 1950s the ''Journal of Philosophy'' consistently reached its Canadian or European subscribers within 30 days of the publication in the US, but we haven’t been able to conclusively rule it out either. If it were possible to prove that this was the case in at least one country with a 50 or 70 years P.M.A. copyright term, then the ''Notes on Logic'' would count as simultaneously published in the US and in that country; therefore, per the Berne Convention, they would have that country as their country of origin; therefore, per the copyright laws of that country, they would now be in the public domain in their country of origin.</ref> In order to determine the copyright status of a work which has the US as its country of origin, knowledge of the date of the author’s death is not sufficient. Per the {{Plainlink|[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Hirtle_chart Hirtle chart]}},<ref name="hirtle-chart"/> the current copyright status of a work first published in the US between 1927 and 1964 depends on whether or not it was published with a copyright notice (which we should assume was the case) and, if it was, on whether or not copyright was renewed before its expiry, the term of which was then 28 years: if copyright was renewed, the text is still copyrighted in the US; if it wasn’t, the text is now in the public domain in the US. Lacking further information, it should be assumed that the copyright on this text was renewed. Assuming that it was indeed renewed, then the duration of its copyright term is 95 years from the publication date, meaning that it will enter the public domain the US on 1 January 2053.<ref name="hirtle-chart" /> | Their country of origin is the US.<ref name="simultaneous">According to the Berne Convention, “The country of origin shall be considered to be: (a) in the case of works first published in a country of the Union, that country; in the case of works published simultaneously in several countries of the Union which grant different terms of protection, the country whose legislation grants the shortest term of protection [...]” (art. 5, par. 4). The definition of “simultaneous publication” is publication in multiple countries within 30 days (see art. 3, par. 4). We haven’t been able to prove that in the 1950s the ''Journal of Philosophy'' consistently reached its Canadian or European subscribers within 30 days of the publication in the US, but we haven’t been able to conclusively rule it out either. If it were possible to prove that this was the case in at least one country with a 50 or 70 years P.M.A. copyright term, then the ''Notes on Logic'' would count as simultaneously published in the US and in that country; therefore, per the Berne Convention, they would have that country as their country of origin; therefore, per the copyright laws of that country, they would now be in the public domain in their country of origin.</ref> In order to determine the copyright status of a work which has the US as its country of origin, knowledge of the date of the author’s death is not sufficient. Per the {{Plainlink|[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Hirtle_chart Hirtle chart]}},<ref name="hirtle-chart"/> the current copyright status of a work first published in the US between 1927 and 1964 depends on whether or not it was published with a copyright notice (which we should assume was the case) and, if it was, on whether or not copyright was renewed before its expiry, the term of which was then 28 years: if copyright was renewed, the text is still copyrighted in the US; if it wasn’t, the text is now in the public domain in the US. Lacking further information, it should be assumed that the copyright on this text was renewed. Assuming that it was indeed renewed, then the duration of its copyright term is 95 years from the publication date, meaning that it will enter the public domain the US on 1 January 2053.<ref name="hirtle-chart" /> | ||

However, in February 2017 Wittgenstein’s Ts-201a1 and Ts-201a2, containing the text of the ''Notes on Logic'', were released by the copyright holders – The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge; Bertrand Russell Archives at McMaster University Library, Hamilton, Ontario; University of Bergen, Bergen – under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC). Therefore, the text should be regarded as being in the public domain in countries where the copyright term is 70 years P.M.A. and licenced under CC BY-NC 4.0 International in the US. As was discussed above in this essay (see [[#Copyright in the age of the internet|§ Copyright in the age of the internet]]), a work being in the public domain in its country of origin is not a requirement for it to be freely reusable, remixable, etc. elsewhere, but rather a generally accepted good practice when the work is to be published on the internet; because of the internet’s lack of national boundaries, in other words, we consider it a good compromise to always make sure that we abide by the rules both of a work’s country of origin and of the country where the work is used, remixed, etc. The situation is similar when a work is not in the public domain in its country of origin but rather is licenced under the terms of a Creative Commons licence: we always want to abide by the rules both of a work’s country of origin and of the country where the work is used, remixed, etc. In this case, this means treating the work (Wittgenstein’s original text) as though it was also licenced under CC BY-NC in Italy. Now, CC BY-NC does not prohibit derivative works (for it does not include the “ND”, “NoDerivatives” clause), nor does it require derivative works to be licenced under the same terms (for it does not include the “SA”, “ShareAlike” clause). Therefore, the LWP’s Italian translation of this text was published under CC BY-SA. | However, in February 2017 Wittgenstein’s Ts-201a1 and Ts-201a2, containing the text of the ''Notes on Logic'', were released by the copyright holders – The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge; Bertrand Russell Archives at McMaster University Library, Hamilton, Ontario; University of Bergen, Bergen – under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC). Therefore, the text should be regarded as being in the public domain in countries where the copyright term is 70 years P.M.A. and licenced under CC BY-NC 4.0 International in the US. As was discussed above in this essay (see [[#Copyright in the age of the internet|§ Copyright in the age of the internet]]), a work being in the public domain in its country of origin is not a requirement for it to be freely reusable, remixable, etc. elsewhere, but rather a generally accepted good practice when the work is to be published on the internet; because of the internet’s lack of national boundaries, in other words, we consider it a good compromise to always make sure that we abide by the rules both of a work’s country of origin and of the country where the work is used, remixed, etc. The situation is similar when a work is not in the public domain in its country of origin but rather is licenced under the terms of a Creative Commons licence: we always want to abide by the rules both of a work’s country of origin and of the country where the work is used, remixed, etc. In this case, this means treating the work (Wittgenstein’s original text) as though it was also licenced under CC BY-NC in Italy, where the work is in the public domain because the copyright term for literary works is 70 years P.M.A.<ref>Italian copyright law only has a specific provision for posthumously published works if the posthumous work is first published after the expiry of copyright. In Wittgenstein’s case, this would only be relevant to writings unpublished as of 1 January 2022. See ''Legge 633/1941,'' article 31 and 85(3).</ref> Now, CC BY-NC does not prohibit derivative works (for it does not include the “ND”, “NoDerivatives” clause), nor does it require derivative works to be licenced under the same terms (for it does not include the “SA”, “ShareAlike” clause). Therefore, the LWP’s Italian translation of this text was published under CC BY-SA. | ||

=== Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway === | === Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway === | ||

The ''Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway'' were first published in Germany in the volume ''Schriften (Band 1. Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Tagebücher 1914-1916. Philosophische Untersuchungen)'', edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1960, pp. 226–253. | The ''Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway'' were first published in Germany in the volume ''Schriften (Band 1. Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Tagebücher 1914-1916. Philosophische Untersuchungen)'', edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1960, pp. 226–253. | ||

Their country of origin is Germany. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.<ref>''Gesetz über Urheberrecht und verwandte Schutzrechte'', section 64.</ref> and the author died before 1952. | Their country of origin is Germany. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.<ref>''Gesetz über Urheberrecht und verwandte Schutzrechte'', section 64. German copyright law does not have specific provisions for posthumously published works.</ref> and the author died before 1952. | ||

=== Tagebücher 1914-1916 === | === Tagebücher 1914-1916 === | ||

| Line 233: | Line 233: | ||

Additionally, it is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1926 and everything that was published before 1 January 1927 is now in the public domain in the US. | Additionally, it is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1926 and everything that was published before 1 January 1927 is now in the public domain in the US. | ||

The preface (''Geleitwort zum Wörterbuch für Volksschulen'') was first published in ''Wörterbuch für Volksschulen'', edited by A. Hübner, E. Leinfellner and W. Leinfellner, Schriften der Österreichischen Wittgensteingesellschaft, Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, Vienna 1977, pp. {{Small caps|xxv}}–{{Small caps|xxxv}}. Its country of origin is Austria. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.<ref>''Bundesgesetz über das Urheberrecht an Werken der Literatur und der Kunst und über verwandte Schutzrechte (Urheberrechtsgesetz)'', BGBl. Nr. 111/1936 – <abbr>BGBl. I Nr. 63/2018, article 60.</abbr></ref> and the author died before 1952. | The preface (''Geleitwort zum Wörterbuch für Volksschulen'') was first published in ''Wörterbuch für Volksschulen'', edited by A. Hübner, E. Leinfellner and W. Leinfellner, Schriften der Österreichischen Wittgensteingesellschaft, Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, Vienna 1977, pp. {{Small caps|xxv}}–{{Small caps|xxxv}}. Its country of origin is Austria. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.<ref>''Bundesgesetz über das Urheberrecht an Werken der Literatur und der Kunst und über verwandte Schutzrechte (Urheberrechtsgesetz)'', BGBl. Nr. 111/1936 – <abbr>BGBl. I Nr. 63/2018, article 60. Austrian copyright law does not have specific provisions for posthumously published works.</abbr></ref> and the author died before 1952. | ||

=== Some Remarks on Logical Form === | === Some Remarks on Logical Form === | ||

| Line 250: | Line 250: | ||

The ''Bemerkungen über Frazers “The Golden Bough”'' were first published in the Dutch journal ''Synthese'', vol. 17, no. 3, Sep. 1967, pp. 233–253. | The ''Bemerkungen über Frazers “The Golden Bough”'' were first published in the Dutch journal ''Synthese'', vol. 17, no. 3, Sep. 1967, pp. 233–253. | ||

Their country of origin are the Netherlands. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.<ref>''Wet van 23 september 1912, houdende nieuwe regeling van het auteursrecht (Auteurswet 1912, tekst geldend op: 01-09-2017)'', articles 37 and 51.</ref> and the author died before 1952. | Their country of origin are the Netherlands. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.<ref>''Wet van 23 september 1912, houdende nieuwe regeling van het auteursrecht (Auteurswet 1912, tekst geldend op: 01-09-2017)'', articles 37(1). Dutch copyright law has a specific provision for posthumously published works, whereby posthumously published works that appeared before 1995 are copyrighted until 50 years after the publication date or until 70 years after the author’s death, whichever term expires the latest. In the case of the ''Bemerkungen über Frazers “The Golden Bough”'', this does not extend the copyright term beyond 1 January 2022. See ''Wet van 23 september 1912, houdende nieuwe regeling van het auteursrecht (Auteurswet 1912, tekst geldend op: 01-09-2017)'', articles 37 and 51.</ref> and the author died before 1952. | ||

=== Blue and Brown Books === | === Blue and Brown Books === | ||

Revision as of 20:27, 8 August 2022

The copyright status of Wittgenstein’s works

31 July 2022

Introduction. The purpose of copyright and the public domain

Before starting to talk about Wittgenstein and his writings, it is important to briefly discuss the purpose of copyright and its general logic. This will help us gain a better understanding of the ethics behind the laws and make sense of what copyright is and what it is not.

Copyright aims to ensure that anyone who performs a creative effort and gives birth to a creative work controls the reproduction and dissemination of such work. Others do not, by default, have the right to copy it – hence the term – without the author’s permission, which is usually granted for a fee. This, in turn, ensures that artists and intellectuals have at least a chance at making a living out of their creative labour.

The concept of “copyright” relies on the understanding that intellectual property is unlike other forms of property in that breaching it – “stealing” – does not mean that the original owner ceases to be in possession of their work. Copies can be made of books, pictures, recordings, etc. that leave the originals intact, whereas stealing gold or cattle means taking it away from someone. “Owning” a book as its author does, for example, as opposed to owning an individual specimen as a reader may, means having legal control over what can and cannot be done with it; “stealing” a book means doing things with it that the author has not agreed to, and this goes way beyond shoplifting an individual specimen.

Thus, the aim of copyright is, among other things, to make creativity viable on the market by giving authors monopoly over the distribution of the copies of their works. By being the only authorised sellers of those works, albeit often with the intermediation of a publisher, or a label, etc., authors may be able to secure an income.

The difference between intellectual property and the property of material goods, however, has implications that reach beyond the relative ease of breaching the former compared to breaching the latter. The very power of culture consists in the possibility for words, pictures, music, etc. to be reproduced with relatively little effort and, most importantly, without thereby consuming, diminishing, or getting any closer to the depletion of the “source”. As the saying – often misattributed to George Bernard Shaw – goes: “If you have an apple and I have an apple and we exchange apples then you and I will still each have one apple. But if you have an idea and I have an idea and we exchange these ideas, then each of us will have two ideas”. The benefit that society as a whole gains from the exchange and the transmission of ideas has long been clear. Therefore, a limitation always accompanies the affirmation of the author’s rights over their works: eventually, copyright expires, and the works become public property. Unlike the property a house, then, which can be handed over from parents to children by way of inheritance for, in principle, endless generations, the intellectual property of a creative work expires two to three generations after the author’s death, depending on the country or territory.

The rationale for the finite duration of the copyright term lies, firstly, in the concept that the circulation of ideas through the replication of works of art (and fiction, and nonfiction) is in the interest of the human community, and not only in the interest of the author and their heirs; and, secondly, it lies in the concept that if such circulation is free not only in the sense of “freedom”, but also in the sense of “free of cost”, the interest of the human spirit will be much better served.

The logic of copyright and of its term being limited by design, thus, is as follows. Authors should be able to exploit their works financially (in order perhaps, depending on one’s broader moral view, to reward their genius, but also to enable them to keep doing what they do while letting others benefit from their creativity as well). Sooner or later, however, the circulation of such works should stop being subject to the author’s consent or their family’s (in order for the public to fully enjoy the works without limitations, and especially without having to pay to do so).

In other words, the “spirit” of copyright laws is that:

- upon the birth[1] of a piece of creative work, the right to copy it, distribute the copies, sell them, modify the original and disseminate the modified version (a translation, a remix, etc.) belongs exclusively to the author – all rights are reserved;

- when the author dies, the abovementioned rights belong, equally exclusively, to the author’s legal heirs for a period of time that, generally speaking, may vary from 30 to 100 years (but is usually 50 or 70);

- then, when the copyright term expires, the work enters the public domain, which means that anyone is legally entitled to copy it, distribute it, sell it, modify it; those who were previously the exclusive holders of the rights are not entitled to any privilege any longer and have, in fact, the same status as all other members of the public; no rights are reserved, except for, in some cases, the few “soft” provisions we call “moral rights” (see below, § Contracts, constraints unrelated to intellectual property, and politeness).

The public domain is meant to be a guarantee that culture is not forever subject to the monetary laws of buying and selling. In spite of local differences in copyright legislation, it is remarkable that in every last country on Earth the copyright term is finite, and all jurisdictions share the moral understanding that it is right for the public to eventually be free to do anything they want with a piece of writing, music, visual art, etc.

The public domain is as important a feature of intellectual property laws as copyright. Attempts at restricting the public’s right to access and use works that are in the public domain should be considered as illegal as accessing and using copyrighted material without permission. Of course, it is much more common for publishers to sue for copyright infringement than for individuals or non-for-profits to sue for what we could call “public domain infringement”. This is due to an obvious imbalance in power – that is, financial resources, knowledge, and organisation – but the argument is not any less urgent for this reason.[2]

A very short history of the rights on Wittgenstein’s writings

Ludwig Wittgenstein died on 29 April 1951. In his last will and testament, he appointed G.E.M. Anscombe, R. Rhees and G.H. von Wright as his literary heirs. Thus, they became the copyright holders for Wittgenstein’s writings.[3]

In the second half of the 20th century, they made (or sometimes delegated) the decisions about what to publish and how, and they had a right to receive royalties for the sales of books.

Rhees died in 1989, Anscombe in 2001, and Von Wright in 2003. Although the author of this essay was unable to find a detailed account of their wills and testaments, it is clear that, after their deaths, the copyright holders for Wittgenstein’s writings became The Master and Fellows of Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. This leads us to think that it was Rhees’s, Anscombe’s, and Von Wright’s joint will to elect Trinity as the heir to the intellectual property of Wittgenstein’s writings.

29 April 2021 was the 70th anniversary of Wittgenstein’s death and on 1 January 2022 Wittgenstein’s writings entered the public domain in those countries where the copyright term is 70 years P.M.A. (post mortem auctoris, i.e., “after the author’s death”). This includes most European countries, much of Africa, Asia and Oceania, and most Latin American Countries. In some jurisdictions, including many African and Asian countries, as well as Canada, where the copyright term is 50 years P.M.A., Wittgenstein’s works were already in the public domain. In some other countries, such as the United States, where copyright laws are rather different than in most other countries and determining the copyright status of a work is not simply a matter of counting the years that have elapsed since the author’s death, some of Wittgenstein’s works are still copyrighted; there, it is still Trinity that counts as the copyright holder.

This map provides a simplified overview of the duration of copyright terms worldwide. Please note that in some countries, for example the US, copyright laws are more complex than elsewhere and knowing that a given number of years has passed since an author’s death is not sufficient for determining the copyright status of their works; in the US, in particular, the publication date of a work often influences its copyright status.[4] Moreover, even in those cases where a country's copyright term is a definite period after the author's death, exceptions may extend copyright further; in France, for example, where the duration of the copyright term is 70 years P.M.A., copyright lasts longer for those authors who died at war and officially count as morts pour la France – among them, famously, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.[5]

In the next few sections, we will examine from the point of view of copyright: the relationship between Wittgenstein’s handwritten or typewritten originals and transcriptions, curated editions, and translations; the relevance, or lack thereof, of the ownership of the material papers to intellectual property; the complications of international copyright law in the age of the internet; the copyright status of individual published works by Ludwig Wittgenstein.

The stratification of copyright

It may happen that creative works themselves become the basis for other creative works. When a text is translated, for example, if the original counts as a creative work, then the translation does too; when a statue or a building are photographed, if the three-dimensional object counts as a creative work, then the two-dimensional image does too; etc.

It is important to understand how layers of copyright function in this kind of scenario, particularly because of how important the issue of transcriptions and translations is for the future of Wittgenstein studies.

The general rule here is quite simple. Obviously, both the creative work which is the starting point of a creative effort (as its material or its subject) and the creative work which is the output of such effort are copyrighted.

In the case of a translation of a book the author of which is still alive, for example, the author is the original text’s copyright holder and may licence another party, typically a publisher, to sell a translation; the translator will be the translation’s copyright holder and may in turn licence another party, again the publisher, to sell the translation. The publisher of the translation will need to have agreements with, and usually pay, both the author and the translator.

When copyright on the original text expires, it becomes possible for anyone to translate it and publish the translation without having to ask for permission. However, extant translations are still copyrighted until their copyright expires. For example, even though Wittgenstein’s Tractatus is now in the public domain in countries with a 70 years P.M.A. copyright term, the Pears-McGuinness translation will be copyrighted in those countries until the 70 years P.M.A. term expires for both Pears and McGuinness, that is, 1 January 2090, for Pears passed before McGuinness and McGuinness passed in 2019. On the other hand, since F.P. Ramsey died at a very young age, many years before Wittgenstein himself, his translation entered (or will enter) the public domain in any given country when the original did (or will).

Since, most often, the translator belongs to a younger generation than the author, “canonical” translations usually enter the public domain significantly later than the corresponding originals.

It must be stressed, however, that for a new “layer” of copyright to be born a creative effort must be involved.

Copyright protects creative works as opposed to mere mechanical labour. This is also true when we talk about a creative work being the subject or the material for something else that may or may not be a creative work itself.

For example, the photograph of a three-dimensional object is universally considered a creative work, because of the choices that need to be made in terms of angle, framing, composition, lighting, focus, focal length, shutter speed, aperture, etc. Even though the Nike of Samothrace is clearly in the public domain, each of the photographs of it that are created daily are protected by copyright.

On the other hand, photocopies and scans are universally considered to be purely mechanical reproductions of two-dimensional objects, and therefore do not entail the formation of a new layer of copyright. This is also true for faithful, frontal photographs of paintings or other two-dimensional works of art. The example here will be much more relevant: since the original handwritten and typewritten notes taken or dictated by Wittgenstein are now in the public domain in most countries, the scans that are available on Wittgenstein Source are now in the public domain too. No matter how expensive or time-consuming scanning thousands of pages was, such effort was not of a creative nature, and copyright laws do not cover its output.[6]

The same is true for verbatim transcriptions. As no creativity is involved, for example, an HTML document that reproduces the text and the formatting of one of Wittgenstein’s manuscripts is not of itself eligible for copyright protection and is in the public domain if the original is. In the context of Wittgenstein studies, the case of the Wittgenstein Archives Bergen’s transcriptions of the Nachlass must now be discussed explicitly.

Under the direction of Profs Claus Huitfeldt and Alois Pichler and over more than 30 years, the WAB has rendered the scholarly community an invaluable service by providing excellent, extremely rich transcriptions of Wittgenstein’s manuscripts and typescripts that, at the moment of this writing, can be accessed online at no cost. Beside the texts, the XML files created by the WAB include all the information which the originals themselves contain – emphases, strikeouts, alternatives, sidenotes, page breaks, and more – and allow the user to dynamically select which information set should be displayed. It is impossible to overestimate the importance of this resource, and the generosity behind the decision – by Trinity and the WAB – to make it available on the internet for free should be duly stressed. The effort that went into making and proofreading the transcriptions should also be recognised. However, this effort cannot count as a creative one.

A transcription, even or rather especially a rich transcription that reproduces all the details of a handwritten or typewritten document, is a 1-to-1 substitution of some visual feature with a corresponding XML tag. If multiple people were to transcribe the same text, the output would have to be absolutely identical: this is enough reason to consider the activity as a non-creative activity.

The same argument, however, can perhaps be expressed in an even more striking way: once a handwritten or typewritten original is transcribed into a rich text document the markup of which incorporates all the information that was present in the original itself, this can (and must, for this is the whole point of the procedure) then be rendered as a document, for example a web page, that visually reproduces all the features of the original; in other words, the visual features of the text (emphases, additions, deletions, etc.) can be transformed into markup and markup can be transformed back into visual features. To put it in a very Wittgensteinian way,[7] the original and the transcription have the same “mathematical multiplicity”, they are in a strong sense interchangeable, and the latter does not add anything creative to the former, no matter how painstakingly long and accurate the procedure is. (Within the frame of this argument, it also becomes even clearer why translations, on the other hand, are and should be considered creative works: there is no way a translation can be “translated back” into the original text: if one tried to reconstruct the German text of the Tractatus by translating an English version back into German, the result would obviously be very different from the original.)[8]

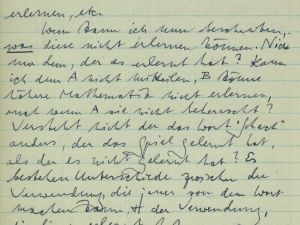

The first image is a scan of Wittgensein’s Ms-176,19v. The second image is the corresponding transcription with HTML markup (for example, the tag <em></em> is for emphasis); the WAB’s XML files are richer (for example, the emphasis tag supports several attributes that correspond to different types of underlined text, etc.) but they are not qualitatively different. The third image is the HTML transcription as viewed in a web browser. The processes that lead from the first picture to the second (encoding) and from the second to the third (rendering) are both 1-to-1 substitutions (images in the Tractarian sense).

It should be added that, from the point of view of Wittgenstein scholarship, the issue of copyright layers is particularly thorny when it comes to assessing the impact of the editors’ work on the very authorship of a published book. In those cases where the editors’ intervention was very significant in selecting and sorting Wittgenstein’s remarks while preparing them for publication, the editors may have to be considered co-authors, thereby extending the copyright term on a work beyond the 70-year period after Wittgenstein’s death. Given the uncertainty of this matter, the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project opted for a cautious approach, which is presented in a separate essay.

When a person is the holder of the copyright on a given work (because they are the author or because they are the author’s heir), they have the right to sign contracts that give others permission to use the work in specific ways under specific conditions. Typically, an author will sign an agreement with a publisher in order for the latter to print, distribute and sell the book and for the former to receive a sum of money in exchange – often a royalty, i.e., a percentage of the cover price of the copies sold.

Regardless of the agreements that copyright holders and publishers may have, however, the expiry of the copyright term is always a sufficient condition for the work to be in the public domain. No contract has the power to extend copyright protection beyond the term defined by the local legislation.

This, as well as the general nature of the public domain itself, is sometimes the subject of misunderstandings because publishers tend to print the copyright symbol “©” or another copyright notice on all books they produce, regardless of the copyright status of the text, possibly hoping to protect the typesetting and layout (which, however, are usually below the threshold of originality)[9] or perhaps simply trying to discourage photocopying even public domain texts. As mentioned above (§ Introduction. The purpose of copyright and the public domain), however, adding copyright symbols where they do not belong should be regarded as illegal.

Additional restrictions may make the picture more complicated.

One such restriction is what we call “moral rights”. Moral rights have to do with the author’s dignity as such and with their unique relationship to their work. The definition of moral rights also varies across jurisdictions, but most often they include the right of attribution and the prohibition that works be remixed in a way that negatively affects the author, their image, or their reputation. This wording may seem to forbid adding a moustache to a reproduction of Mona Lisa or creating a horror version of Winnie-the-Pooh, but in practice such things are widely accepted, as long as it is clear that the parody or distortion is attributable to the remixer, and not to the author. Moral rights have no import as far as copyright and the public domain are concerned, and no financial import whatsoever. In some countries, they do not expire.

Another set of restrictions may arise from the fact that, even after copyright expires, ownership of the original specimen remains. Thus, for example, the Louvre may well forbid visitors to take photos of its paintings – even though most of the works in the museum are out of copyright – simply because they have the authority to dictate the house rules; on the other hand, they have no authority to forbid us to freely share, modify and even sell the faithful reproductions of public-domain two-dimensional works that can be found on their very website. In the case of Wittgenstein, his originals have several different owners – the Wren Library, Trinity College, Cambridge; the Austrian National Library, Vienna; the Bodleian Library, Oxford; the Noord Hollands Archief, Haarlem; the Bertrand Russell Archives, McMaster University Library, Hamilton[10] – but this also has no import as far as copyright and the public domain are concerned.

Finally, even in the arid landscape of copyright law and the harsh arena of the publishing business, politeness and bona fides are not without importance. It remains a good practice to inform the former copyright holders or the owners of the originals when a new edition or translation of a public-domain text is planned; and it is crucial that projects which share the same goal of improving the availability of a given cultural asset to the public are well coordinated, do not uselessly compete with each other, and on the contrary work together in a spirit of cooperation or, at least, complementarity. This is as good a place as any to say that if the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project were to fail to comply with these basic rules of manners it would not be because of a slapdash attitude, but because of a failure to identify some of the many stakeholders.

Copyright in the age of the internet

It was mentioned above that breaching intellectual property rules is somewhat easier than breaching regular property rules, at least insofar as the “stolen” object is not taken away from the owner and it may even be difficult for them to realise that they have been robbed.

Computers and the internet have made copying creative works and distributing them easier than ever before. They have, therefore, multiplied the instances of copyright infringement. (As a side note, it should be remarked that they have also multiplied the instances of lawful distribution of copyrighted material for a fee, thereby significantly enriching the publishers that have taken advantage of the newer media.)

Copyright law has changed remarkably little to meet the challenges of the digital age. The most significant innovation in the landscape of copyright law since the beginning of the 21st century has been the codification and the spread of the Creative Commons licences, which will be briefly discussed below, in § The Creative Commons licences. Other than that, the world’s copyright system is not designed for the digital age, and often seems to be altogether unfit for it.

One of the challenges for those who are looking to lawfully share out-of-copyright content in a digital format is the fact that the web is an intrinsically international space – it is, after all, the worldwide web – and within it national borders are almost non-existent.

As far as copyright is concerned, international relations are still largely regulated by the Berne Convention,[11] adopted in 1886 and last amended in 1979. This document establishes that signatory countries must grant copyright protection to all works that have another signatory country as their country of origin.

Now, because copyright rules are very much country-specific, it is common for a work to be copyrighted according to the laws of a given country and in the public domain according to the laws of another. For example, Soldier’s Pay, William Faulkner’s first novel, published in 1926, is in the public domain in the US, where everything that was published before 1927 is now out of copyright; it is, however, copyrighted in the European Union, because Faulkner died in 1962 and the EU’s copyright term lasts 70 years after the author’s death. For the same reason, Wittgenstein’s Tractatus was already in the public domain in the US in 2021, when it was still copyrighted in the European Union.

What does it mean, then, to lawfully share out-of-copyright content on the web? Should we wait until the content is out of copyright according to the laws of every last country on Earth? This would clash with the principle, stated above, that the public’s right to access public domain works should not be limited beyond what a given legislation already does. Should we consider it enough for the copyright term to have expired in the country where the website is based, even though the location of the servers or the legal registration may be immaterial as far as the location of the audience is concerned? This would expose the site to the risk of being considered a pirate website, and therefore being blocked, in counties that have a longer copyright term.[12]

There is no definite answer to this question, precisely because there is no international treaty with provisions that take into account the contemporary state of information technology. A viable solution, however, is that of respecting two requirements while publishing works on the internet: for them to be in the public domain, or at least reusable (with reference to the relevant cases, the difference will be discussed in § The copyright status of Wittgenstein’s individual works), in the country where the website is located and in their country of origin.

This is, for example, the policy of the Wikimedia projects,[13] which have earned a very respectable position among those who are trying to challenge the traditional closed culture system while abiding by its rules.

The notion of “country of origin” is a traditional concept that is defined by the Berne Convention itself. Even though its application is not always obvious when a work is first published in a digital format, for it may then be considered to be simultaneously published throughout the world,[14] determining the country of origin of a work that was first published in print is rather straightforward:

The question should then be answered: what does it mean for a website to be located in a certain country? This question is rather complex for high-traffic sites which, to better serve requests, have servers in many locations and for sites which are operated by multinational companies; it is, however, quite simple in the case of the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project, since our servers are located in Italy and the owner of the website is both Italian and based in Italy. The Ludwig Wittgenstein Project therefore operates under Italian laws and European Union regulations.

Finally, it should be noted that the policy according to which the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project only publishes works that are free in their country of origin and in Italy, in spite of adhering to a widely accepted best practice, does not of itself solve the problem posed by the fact that some of the texts that are available on our site are not in the public domain in some countries, for example Mexico, where the copyright term is 100 years P.M.A. It is the reader’s responsibility to comply with the laws of their country by making sure that a given work is in the public domain there before accessing it or downloading it. Still, nothing would prevent a country where some of the materials that we publish are not in the public domain, for example Mexico, from blocking access to the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project’s site for users located within its territory.

The Creative Commons licences

Before moving on, it is now appropriate to provide a very short introduction to Creative Commons Licences. This is for three reasons:

- as it was claimed in the previous section of this essay, they are probably the most meaningful innovation in the field of intellectual property since the advent of the internet;

- as we will see in the last section of this essay (see § The copyright status of Wittgenstein’s individual works), some of Wittgenstein’s works have been released by their copyright holders under the terms of Creative Commons licences;

- the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project releases all its original content under Creative Commons licences.

Creative Commons licences provide a simple solution for creators to publish their works under terms that, on the one hand, allow others to use them for free and, on the other hand, require the party who uses the content to meet a variable set of conditions, based on the creator’s own choice. Their introduction was prompted by the realisation that, given the ease of sharing texts, pictures and multimedia files brought about by the web, an increasing number of people would be happy to publish their creative works outside of a commercial logic, i.e., without the hope or even the intention of making money out of their sale, but would still want to reserve some rights.

Devised by a team of legal experts led by Lawrence Lessig and first released in 2002, the six Creative Commons licences are based on the recognition of three freedoms and four constraints.[16] The three freedoms are:

- the right to share a work, meaning to duplicate it, republish it, distribute it;

- the right to remix a work, that is, to edit a picture, translate a text, remix an audio track in the strict sense or otherwise create a derivative work based upon the original;

- the right to sell a work, that is to use the original or a work derived from the original commercially.

The four constraints are:

- the requirement to attribute the work, that is, to cite the author or authors;

- the requirement to share derivative works, if any, under the same licence as the original;

- the prohibition to sell the work or a work derived from it, or otherwise use it commercially;

- the prohibition to remix the work, meaning that no works can be derived from it.

The combinations of these freedoms and constraints generates the six licences, listed below from the “most free” to the “least free”:

- Creative Commons Zero (CC0): a waiver equivalent to the public domain, where the author grants permission to use the work for all purposes without any limitations, not even requiring attribution; it should be noted that CC0 is not strictly speaking a licence, but is rather referred to as a “tool” for relinquishing one’s rights;

- Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY): the work can be used for all purposes, but the author must be credited;

- Creative Commons Attribution – ShareAlike (CC BY-SA): the work can be used for all purposes, but the author must be credited and derivative works, if any, must also be licenced under CC BY-SA;

- Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial (CC BY-NC): the work can be used for non-commercial purposes only; the author must be credited;

- Attribution – NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA): the work can be used for non-commercial purposes only; the author must be credited and derivative works, if any, must also be licenced under CC BY-NC-SA.

- Attribution – NoDerivatives (CC BY-ND): the work can be used for all purposes, but it cannot be remixed; the author must be credited;

- Attribution – NonCommercial – NoDerivatives (CC BY-NC-ND): the work can be used for non-commercial purposes only, and it cannot be remixed; the author must be credited.

Creative Commons Attribution and Attribution – ShareAlike are considered “free” licences because they allow reusing the work for any purpose, including commercially, and remixing it; in this sense, the other licences are “non-free”, even though they still allow reusing the work and, in some cases, remixing it under stricter conditions.

The copyright status of Wittgenstein’s individual works

In this section, we will apply the concepts described above in order to clarify the copyright status of Wittgenstein’s works.[17] We will limit ourselves to those that have been published on the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project’s website, thereby excluding those texts where the editors may have to be counted as co-authors.

For each work, the copyright status in the country of origin and in Italy will be described and explained.[18] What is written about Italy can be considered to be valid, to some extent, for all countries where, as a general rule, copyright expires 70 years or fewer P.M.A.; however, since local exceptions may exist,[19] generalisations should be made, so to speak, at one’s own risk. Occasionally, the copyright status in the United States will be discussed, as the US, despite not playing any special role from the point of view of the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project, are certainly, to this day, the centre of gravity of the web.

The information is valid and up to date as of July 2022. Copyrights that are still standing will gradually expire in the coming years and decades.

Review of P. Coffey, “The Science of Logic”

The Review of P. Coffey, “The Science of Logic” was first published in the British journal The Cambridge Review, vol. 34, no. 853, 6 Mar. 1913, p. 351.

Its country of origin is the United Kingdom. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.[20][21] and the author died before 1952.

Additionally, it is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1913 and everything that was published before 1 January 1927 is now in the public domain in the US.[4]

Notes on Logic

The Notes on Logic were first published in the United States of America, in the journal The Journal of Philosophy, 54, 1957, pp. 230–245.

Their country of origin is the US.[22] In order to determine the copyright status of a work which has the US as its country of origin, knowledge of the date of the author’s death is not sufficient. Per the Hirtle chart,[4] the current copyright status of a work first published in the US between 1927 and 1964 depends on whether or not it was published with a copyright notice (which we should assume was the case) and, if it was, on whether or not copyright was renewed before its expiry, the term of which was then 28 years: if copyright was renewed, the text is still copyrighted in the US; if it wasn’t, the text is now in the public domain in the US. Lacking further information, it should be assumed that the copyright on this text was renewed. Assuming that it was indeed renewed, then the duration of its copyright term is 95 years from the publication date, meaning that it will enter the public domain the US on 1 January 2053.[4]

However, in February 2017 Wittgenstein’s Ts-201a1 and Ts-201a2, containing the text of the Notes on Logic, were released by the copyright holders – The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge; Bertrand Russell Archives at McMaster University Library, Hamilton, Ontario; University of Bergen, Bergen – under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC). Therefore, the text should be regarded as being in the public domain in countries where the copyright term is 70 years P.M.A. and licenced under CC BY-NC 4.0 International in the US. As was discussed above in this essay (see § Copyright in the age of the internet), a work being in the public domain in its country of origin is not a requirement for it to be freely reusable, remixable, etc. elsewhere, but rather a generally accepted good practice when the work is to be published on the internet; because of the internet’s lack of national boundaries, in other words, we consider it a good compromise to always make sure that we abide by the rules both of a work’s country of origin and of the country where the work is used, remixed, etc. The situation is similar when a work is not in the public domain in its country of origin but rather is licenced under the terms of a Creative Commons licence: we always want to abide by the rules both of a work’s country of origin and of the country where the work is used, remixed, etc. In this case, this means treating the work (Wittgenstein’s original text) as though it was also licenced under CC BY-NC in Italy, where the work is in the public domain because the copyright term for literary works is 70 years P.M.A.[23] Now, CC BY-NC does not prohibit derivative works (for it does not include the “ND”, “NoDerivatives” clause), nor does it require derivative works to be licenced under the same terms (for it does not include the “SA”, “ShareAlike” clause). Therefore, the LWP’s Italian translation of this text was published under CC BY-SA.

Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway

The Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway were first published in Germany in the volume Schriften (Band 1. Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Tagebücher 1914-1916. Philosophische Untersuchungen), edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1960, pp. 226–253.

Their country of origin is Germany. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.[24] and the author died before 1952.

Tagebücher 1914-1916

The Tagebücher 1914-1916 were first published in Germany in the volume Schriften (Band 1. Tractatus logico-philosophicus. Tagebücher 1914-1916. Philosophische Untersuchungen), edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1960, pp. 85–278.

Their country of origin is Germany. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung

The Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung was first published in Germany in the journal Annalen der Naturphilosophie, no. 14, 1921, pp. 185–262.

Its country of origin is Germany. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

Additionally, it is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1921 and everything that was published before 1 January 1927 is now in the public domain in the US.[4]

Wörterbuch für Volks- und Bürgerschulen

The Wörterbuch für Volks- und Bürgerschulen was first published in Austria as Wörterbuch für Volksschulen, Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, Vienna 1926.

Its country of origin is Austria. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

Additionally, it is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1926 and everything that was published before 1 January 1927 is now in the public domain in the US.

The preface (Geleitwort zum Wörterbuch für Volksschulen) was first published in Wörterbuch für Volksschulen, edited by A. Hübner, E. Leinfellner and W. Leinfellner, Schriften der Österreichischen Wittgensteingesellschaft, Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, Vienna 1977, pp. xxv–xxxv. Its country of origin is Austria. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.[25] and the author died before 1952.

Some Remarks on Logical Form

Some Remarks on Logical Form was first published in the British journal Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, supplementary vol. 9, London 1929, pp. 162–171.

Its country of origin is the United Kingdom. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

Lecture on Ethics

The Lecture on Ethics was first published in the United States of America, in the journal The Philosophical Review, vol. 74, no. 1, Jan. 1965, pp. 3–12.

Its country of origin is the US.[22]

However, in February 2017 the text of Wittgenstein’s Ts-207 was released by the copyright holders – The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge and the University of Bergen, Bergen – under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. Therefore, the text should be regarded as being in the public domain in countries where the copyright term is 70 years PMA and licenced under CC BY-NC 4.0 International in the US. See above, § Notes on Logic, for more details.

Bemerkungen über Frazers “The Golden Bough”

The Bemerkungen über Frazers “The Golden Bough” were first published in the Dutch journal Synthese, vol. 17, no. 3, Sep. 1967, pp. 233–253.

Their country of origin are the Netherlands. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A.[26] and the author died before 1952.

Blue and Brown Books

The Blue Book and the Brown Book were first published in the United Kingdom in the volume Preliminary Studies for the “Philosophical Investigations”. Generally Known as The Blue and Brown Books, Blackwell, Oxford 1958.

Their country of origin is the United Kingdom. These works are in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

Philosophische Untersuchungen

The Philosophische Untersuchungen were first published in the United Kingdom as Philosophische Untersuchungen, edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and R. Rhees, Blackwell, Oxford 1953.

Their country of origin is the United Kingdom. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

Zettel

The Zettel were first published in the United Kingdom as Zettel, edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright, Blackwell, Oxford 1967.

Their country of origin is the United Kingdom. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

Bemerkungen über die Farben

The Bemerkungen über die Farben were first published in a traditional book form in the United Kingdom as Bemerkungen über die Farben, edited by G.E.M. Anscombe, Blackwell, Oxford 1977.

If this were to count as the first edition, their country of origin would be the United Kingdom. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

However, Ms-172, Ms-173, and Ms-176, in which Wittgenstein’s remarks on colour are contained and from which the 1977 edition was compiled, had already been published, albeit in a rather uncommon kind of edition. In 1967, looking to make the Nachlass available to scholars in its “raw” form, Cornell University microfilmed the corpus; the print version of the microfilms, i.e., a facsimile edition of (almost) the entire Nachlass, was published by Cornell itself in 1968.[27] Even though it is a rather untypical book and even though, in particular, it lacks an imprint, the Cornell edition seems to meet the American legal definition of “publication”[28] and the Bemerkungen über die Farben, which were part of this publication,[29] must therefore be considered to have the US as their country of origin. Possibly because of being published by a university library for mere research purposes, however, this edition did not bear a copyright notice. Works first published in the US between 1927 and 1977 without a copyright notice are in the public domain there, because at the time this formality was a necessary condition for the work to be copyrighted at all.[4] Thus, the Bemerkungen über die Farben are in the public domain in their country of origin. If, on the other hand, the Cornell edition does not in fact meet the American legal definition of publication, then it must again count as having first been published in the United Kingdom in 1977, and so again it is in the public domain in its country of origin.

Über Gewißheit

Über Gewißheit was first published in a traditional book form in the United Kingdom as Über Gewißheit, edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright, Blackwell, Oxford 1969.

If this were to count as the first edition, its country of origin would be the United Kingdom. This work is in the public domain there, as well as in Italy, because the copyright term for literary works in both countries is 70 years P.M.A. and the author died before 1952.

However, Ms-172, Ms-173, Ms-174, Ms-175, and Ms-176, in which Wittgenstein’s remarks on certainty are contained and from which the 1969 edition was compiled, had previously appeared in the Cornell edition (see § Bemerkungen über die Farben). Über Gewißheit must therefore be considered to have the US as its country of origin and it is in the public domain there because it was published without complying with the formalities that were necessary at the time.

- ↑ The author would like to thank Dr Jasmin Trächtler, Mr David Chandler, and Mr Javier Arango for reviewing this text. Additionally, he would like to extend sincere gratitude to Dr Nicolas Bell, the Librarian of Trinity College, who provided insightful comments on a draft of this essay.

- ↑ Generally speaking, it is not necessary to publish or register a work, or to comply with any formalities at all, in order for it to be copyrighted. This, however, has not always been the case everywhere in the world: because for many decades in the 20th century US law required creative works to bear a copyright notice (for example the copyright symbol “©” followed by the publication date and the author’s name) in order for them to be copyrighted, many works that did not comply with this simple formality were directly, albeit often inadvertently, released in the public domain.

- ↑ The very concept of “public domain infringement”, obviously formed in analogy with “copyright infringement”, was coined by the author of this essay. Merely as a proof that the broad moral framework of our culture warrants the analogy, consider articles 27 (“Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author”) and 19 (“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- ↑ See This is the last will of me Ludwig Wittgenstein, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, retrieved 16 July 2002 (archived URL).

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 See Copyright Term and the Public Domain, Cornell University Library, retrieved 30 July 2022 (archived URL).

- ↑ See Durée des droits d’auteur, Syndicat national de l'édition, 2 Novembre 2017, retrieved 30 July 2022 (archived URL)

- ↑ For further details on this subject, see Thomas Margoni, The digitisation of cultural heritage: originality, derivative works and (non) original photographs, Institute for Information Law (IViR), Faculty of Law, University of Amsterdam, p. 51.

- ↑ See Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 4.04.

- ↑ Of course, the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project has no intention to duplicate the WAB’s excellent work and even less to overshadow it. The scope of our project is, and is meant to be, complementary to theirs, in that we aim to make edited Leseausgaben available as opposed to “raw” source materials and our target audience is the general public as opposed to the academics. Se the following section, § Contracts, constraints unrelated to intellectual property, and politeness, for a brief comment on “politeness” in this context.

- ↑ It may be worth noting, incidentally, that some countries do have “typographical copyrigh”, i.e., laws that specifically protect typesetting and layout. The UK is one such country: see Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, section 15.

- ↑ UNESCO Certificate and Nomination Form, Wittgenstein Initiative, 25 January 2018, retrieved 16 July 2022 (archived URL).

- ↑ More information on the Berne Convention, as well as the full text of the document, can be found on the website of the WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization): Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works.

- ↑ The website of Project Gutenberg, for example, is currently inaccessible in Italy and, for a limited period of time, it was inaccessible in Germany: the site was blocked by local authorities because, among many others, it featured works that were in the public domain in the United States but not in Europe.

- ↑ For a rich overview of the policy adopted on Wikimedia Commons, the Wikimedia repository of images, scanned texts and other multimedia files, see the Copyright rules by territory Commons page.

- ↑ For further details on this subject, see Chris Dombkowski, “Simultaneous Internet Publication and the Berne Convention”, in Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal, vol. 29, no. 4, 23 May 2013.

- ↑ Brian Fitzgerald, Sampsung Xiaoxiang Shi, Cheryl Foong, and Kylie Pappalardo, “Country of Origin and Internet Publication: Applying the Berne Convention in the Digital Age”, in Brian Fitzgerald and John Gilchrist (eds.), Copyright Perspectives, Springer, 2015, retrieved 16 July 2022 (archived URL).

- ↑ For more information, see the relevant page of the Creative Commons website: Creative Commons Licenses.

- ↑ Information about first editions was taken from Alois Pichler, Michael A. R. Biggs, Sarah Anna Szeltner, “Bibliographie Der Deutsch- Und Englischsprachigen Wittgenstein-Ausgaben”, in Wittgenstein-Studien, 2011 (updated 2019) (archived URL).

- ↑ In the paragraphs below, when a country’s copyright term is mentioned for the first time, the relevant intellectual property law is cited – except in the case of the US, where the reference is to a secondary source. Each of the cited laws is listed by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) as the main IP law enacted by the relevant legislature.

- ↑ As an example, it is worthwhile to briefly discuss an issue that often comes up in conversations between Wittgensteinians about copyright. In the UK, as a general rule, copyright expires 70 years P.M.A. However, texts that were unpublished as of the end of 1989 will be copyrighted until the end of 2039 regardless of the date of the author’s death. For further information, see Copyright Notice: Duration of copyright (term), UK Intellectual Property office, 15 January 2021, retrieved 16 July 2022 (archived URL). This does not affect any of the texts published on the Ludwig Wittgenstein Project’s website, but those among Wittgenstein’s manuscripts that were indeed unpublished as of 1989 are still copyrighted in the UK.

- ↑ Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, section 12 (2).

- ↑ Legge 633/1941, article 25.

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 According to the Berne Convention, “The country of origin shall be considered to be: (a) in the case of works first published in a country of the Union, that country; in the case of works published simultaneously in several countries of the Union which grant different terms of protection, the country whose legislation grants the shortest term of protection [...]” (art. 5, par. 4). The definition of “simultaneous publication” is publication in multiple countries within 30 days (see art. 3, par. 4). We haven’t been able to prove that in the 1950s the Journal of Philosophy consistently reached its Canadian or European subscribers within 30 days of the publication in the US, but we haven’t been able to conclusively rule it out either. If it were possible to prove that this was the case in at least one country with a 50 or 70 years P.M.A. copyright term, then the Notes on Logic would count as simultaneously published in the US and in that country; therefore, per the Berne Convention, they would have that country as their country of origin; therefore, per the copyright laws of that country, they would now be in the public domain in their country of origin.

- ↑ Italian copyright law only has a specific provision for posthumously published works if the posthumous work is first published after the expiry of copyright. In Wittgenstein’s case, this would only be relevant to writings unpublished as of 1 January 2022. See Legge 633/1941, article 31 and 85(3).

- ↑ Gesetz über Urheberrecht und verwandte Schutzrechte, section 64. German copyright law does not have specific provisions for posthumously published works.

- ↑ Bundesgesetz über das Urheberrecht an Werken der Literatur und der Kunst und über verwandte Schutzrechte (Urheberrechtsgesetz), BGBl. Nr. 111/1936 – BGBl. I Nr. 63/2018, article 60. Austrian copyright law does not have specific provisions for posthumously published works.

- ↑ Wet van 23 september 1912, houdende nieuwe regeling van het auteursrecht (Auteurswet 1912, tekst geldend op: 01-09-2017), articles 37(1). Dutch copyright law has a specific provision for posthumously published works, whereby posthumously published works that appeared before 1995 are copyrighted until 50 years after the publication date or until 70 years after the author’s death, whichever term expires the latest. In the case of the Bemerkungen über Frazers “The Golden Bough”, this does not extend the copyright term beyond 1 January 2022. See Wet van 23 september 1912, houdende nieuwe regeling van het auteursrecht (Auteurswet 1912, tekst geldend op: 01-09-2017), articles 37 and 51.

- ↑ The Wittgenstein Papers, Cornell University Libraries, Ithaca (NY) 1968. For more information, see A. Pichler, “Encoding Wittgenstein. Some Remarks on Wittgenstein’s Nachlass, the Bergen Electronic Edition, and future electronic publishing and networking”, in Trans. Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften, no. 10, January 2022, retrieved 30 July 2022 (archived URL).

- ↑ “‘Publication’ is the distribution of copies or phonorecords of a work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending.” Title 17 of the United States Code (17 U. S. C.) §101. By this definition, there is no minimum number of copies to be attained for the distribution to count as a publication, nor there is the need for a formal registration or commercialisation. As Peter Hirtle writes, however, the following should be noted: “‘Publication’ was not explicitly defined in the Copyright Law before 1976, but the 1909 Act indirectly indicated that publication was when copies of the first authorized edition were placed on sale, sold, or publicly distributed by the proprietor of the copyright or under his authority.” See Copyright Term and the Public Domain, Cornell University Library, retrieved 30 July 2022 (archived URL). The 1909 indication seems to stress commercialisation more than Title 17 does; at any rate, it seems that the Cornell edition was indeed sold to research institutes worldwide: see A. Pichler, “Encoding Wittgenstein. Some Remarks on Wittgenstein’s Nachlass, the Bergen Electronic Edition, and future electronic publishing and networking”, in Trans. Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften, no. 10, January 2022, retrieved 30 July 2022 (archived URL).

- ↑ M. Biggs, A. Pichler, “Wittgenstein: Two Source Catalogues and a Bibliography. Catalogues of the Published Texts and of the Published Diagrams, each Related to its Sources”, in Working Papers from the Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen, no. 7, 1993.

About Us · About Wittgenstein · People · Quality Policy · Contacts · FAQ