Project:About Wittgenstein: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

<!--{{Drawer|number=4 | <!--{{Drawer|number=4 | ||

|title=Philosophical Investigations | |title=Philosophical Investigations | ||

|content=-->"Philosophical Investigations" is the title that Wittgenstein, starting from the mid-1930s, | |content=-->"Philosophical Investigations" is the title that Wittgenstein, starting from the mid-1930s, attributed to a collection of German-language manuscripts, often converted into typescripts, which he repeatedly, extensively, and compulsively revised in an attempt to shape his second book of philosophy. Even if the resulting typescript (Ts-227 in von Wright's catalogue) is considered to be the most polished among the later Wittgenstein's writings, the book did not see the light of day during the author's lifetime: it was only in 1953 that Wittgenstein's literary executors posthumously published the text along with G.E.M. Anscombe’s English translation, in a form that has not failed to provoke criticism due to the inclusion of a so-called “Part II” of the work. The content of this section consists of materials written between 1947 and 1949, which Wittgenstein made a selection of and had typed out (the resulting typescript was catalogued as Ts-234). G.E.M. Anscombe and Rush Rhees claimed that it was his intention to incorporate these contents into the final version of the work, but they also made it clear that it was their decision to attach "Part II", in its relatively "raw" form, to the relatively "finished" text of "Part I". Additionally, the themes discussed in "Part II" are more closely related to the work Wittgenstein carried out on the philosophy of psychology after 1945. For these reasons, on our website, we exclusively reproduce what is known as "Part I" of the work, as do an increasing number of recent editions of the ''Philosophical Investications'' – for example, Joachim Schulte's [https://www.suhrkamp.de/buch/ludwig-wittgenstein-philosophische-untersuchungen-t-9783518223727 German edition]. Schulte also observes that the integration proposed by the literary executors, while it was welcome at the time of publication as it allowed the reader of the ''Investigations'' to become acquainted with reflections by Wittgenstein that would otherwise have remained unknown for many years, is now superfluous, because the content of "Part II" is now widely available thanks to the electronic editions of the ''Nachlass''. | ||

Although the final version of the first part of the work was only composed between 1943 and 1945, with some marginal rehashes thereafter, it would be flawed to argue that the ''Investigations'' reflect Wittgenstein's thought limited to the | Although the final version of the first part of the work was only composed between 1943 and 1945, with some marginal rehashes thereafter, it would be flawed to argue that the ''Investigations'' reflect a phase of Wittgenstein's thought whose scope is limited to the early 1940s. As he writes in the Preface, the ideas contained in the book are "the precipitate of philosophical investigations which have occupied me for the last sixteen years". Therefore, the ''Philosophical Investigations'' can be considered a synthesis of Wittgenstein's mature thought, following his return to philosophy in 1929. Once again, the result of years of gestation was a complex work, devoid of a hierarchical structure and a definitive status unlike the ''Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus'', but equally rich and surprising. | ||

In the 693 numbered paragraphs of the first part of the work, which follow slender and rarely explicit logical threads, Wittgenstein addresses many subjects, as summarized in the Preface: “the concepts of meaning, of understanding, of a proposition and sentence, of logic, the foundations of mathematics, states of consciousness, and other things”, without, however, providing a systematic treatment of them, but rather free remarks or, as the author puts it, “a number of sketches of landscapes which were made in the course of those long and meandering journeys”. This method corresponds to a renewed conception of the nature of the philosophical enterprise, which Wittgenstein presents in paragraphs 109-133: as he had already argued in the ''Tractatus'', the aim is to solve philosophical pseudo-problems by dissolving the confusions that arise in the everyday use of language. However, for the author of the ''Investigations'', this activity of clarification no longer involves a refinement of the linguistic code according to ideal, logical criteria. “Every sentence in our [ordinary] language is in order as it is” ([[Philosophische Untersuchungen#98|§ 98]]): these kind of observations convey the idea that the principles that define the meaningfulness of language reside within language itself, and its intelligibility does not derive from compliance with logical rules, but rather from "grammatical" rules, that is, from the overall evaluation of the diverse uses of signs. Consequently, the philosopher's task does not consist in providing explanations about the nature of language, but rather in offering descriptions of language use, thus elucidating the inconspicuous implications of the linguistic activity that are not immediately recognizable. | In the 693 numbered paragraphs of the first part of the work, which follow slender and rarely explicit logical threads, Wittgenstein addresses many subjects, as summarized in the Preface: “the concepts of meaning, of understanding, of a proposition and sentence, of logic, the foundations of mathematics, states of consciousness, and other things”, without, however, providing a systematic treatment of them, but rather free remarks or, as the author puts it, “a number of sketches of landscapes which were made in the course of those long and meandering journeys”. This method corresponds to a renewed conception of the nature of the philosophical enterprise, which Wittgenstein presents in paragraphs 109-133: as he had already argued in the ''Tractatus'', the aim is to solve philosophical pseudo-problems by dissolving the confusions that arise in the everyday use of language. However, for the author of the ''Investigations'', this activity of clarification no longer involves a refinement of the linguistic code according to ideal, logical criteria. “Every sentence in our [ordinary] language is in order as it is” ([[Philosophische Untersuchungen#98|§ 98]]): these kind of observations convey the idea that the principles that define the meaningfulness of language reside within language itself, and its intelligibility does not derive from compliance with logical rules, but rather from "grammatical" rules, that is, from the overall evaluation of the diverse uses of signs. Consequently, the philosopher's task does not consist in providing explanations about the nature of language, but rather in offering descriptions of language use, thus elucidating the inconspicuous implications of the linguistic activity that are not immediately recognizable. | ||

Revision as of 14:20, 30 June 2023

About Us · About Wittgenstein · People · Quality Policy · Contacts · FAQ

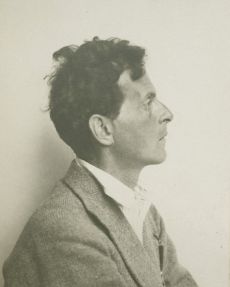

Essential biography

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (Vienna, 26 April 1889 – Cambridge, 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-born philosopher who mostly worked and taught at the University of Cambridge. He is widely considered one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century.

Born into a wealthy bourgeois family, the young Wittgenstein was acquainted with some of the most important figures of Viennese fin de siècle culture (Johannes Brahms, Gustav Klimt, Gustav Mahler, Karl Kraus). While completing his studies in mechanical engineering in Manchester, Wittgenstein developed a keen interest in logic and the philosophy of mathematics through the works of Gottlob Frege (1948–1925) and Bertrand Russell (1872–1970). He moved to Cambridge in 1911 to attend courses taught by Russell, who immediately noticed Wittgenstein's sharp perspicacity, as well as his troubled attitude.

Later, Wittgenstein spent some time (1913–1914) in Skjolden, Norway, where he wrote and dictated his first works on logic (the Notes on Logic and the Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore in Norway). At the outbreak of World War I, he enlisted as a volunteer in the Austrian army. The war was one of the most influential experiences of Wittgenstein’s life. Amid the harshness of the conflict, his first work – the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, completed during his imprisonment in Cassino (1918–1919) – came to light. The book was first published in 1921 as a German edition, of which the author disapproved, and later in 1922 as an English translation by Wittgenstein’s friend Frank Ramsey (1903–1930). The Tractatus was the only philosophy book that Wittgenstein published during his lifetime.

Turning away from philosophical thought, from 1922 to 1928 Wittgenstein devoted himself to teaching elementary school in a small Austrian village, to architecture – he built his sister Margarete’s house – and to working as a gardener in a convent. The newly-founded, neo-positivist Vienna Circle took an interest in his work, which elicited rather cold reactions on Wittgenstien's part.

In 1928, however, a conference held by mathematician Luitzen Brouwer (1881–1966) in Vienna reawakened Wittgenstein's interest in philosophy, convincing him to move back to Cambridge, where he obtained the teaching qualification. The years from 1928 to 1941 are remembered as a period in which the logical-philosophical theories of the Tractatus were thoroughly reconsidered: starting with the Lecture on Ethics (delivered in 1929), he revised and modified his ideas on language, logic, the foundations of mathematics, psychology, anthropology, and symbolic forms. The result of these reflections was collected in a series of manuscripts and typescripts written by Wittgenstein himself, or transcribed by his students during lectures. These include the Philosophical Remarks, Philosophical Grammar, the Big Typescript, the Blue Book and the Brown Book, and Zettel.

During World War II, Wittgenstein served in a civilian hospital. Between 1947 and 1950 he spent time in England, Ireland, and the USA. Between 1949 and 1951 he wrote the remarks that were later published as On Certainty. But his best known and most memorable, albeit unfinished work from this period remains the Philosophical Investigations, the masterpiece of the “later” Wittgenstein, which, ever since its publication in 1953, has been fertile ground for contemporary philosophy.

In his last years, Wittgenstein deepened his acquaintances with G.H. von Wright (1916–2003), Rush Rhees (1905–1989) and G.E.M. Anscombe (1919–2001), who later became his literary executors and published much of his posthumous work. He died in 1951 at the age of 62.

His most famous words: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” (Tractatus logico-philosophicus, 7). His last words: “Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life”.

An outline of Wittgenstein’s thought

Wittgenstein’s philosophical works touched upon numerous critical points in contemporary philosophy. It is not incorrect to say that Wittgenstein’s major concern throughout his life was the investigation of language, but it would be reductive to limit the scope of his thought to the philosophy of language and logic. Wittgenstein was influenced by Hertz, Frege, and Russell, but also by Kraus, Spengler, Weininger, Schopenhauer, Tolstoy, and Kierkegaard. Nor were his influences limited to the philosophical sphere: Wittgenstein was an attentive reader of Goethe and an appreciator of German poetry. Music, moreover, and particularly the classical romantic music of the Liederists and Brahms, remained one of Wittgenstein's primary sources of inspiration.

At the time of the Tractatus's writing, the influence of the prevailing logicism framed Wittgenstein's consideration of symbolism in a representational and “realist” perspective, although he brought brilliant innovations to coeval philosophy. The key idea of this first book is the distinction between what can be said (or represented, i.e., the facts in the world) and what can only be shown (i.e., the forms of representation). The Tractatus aims to delimit the realm of meaningful propositions to the realm of science and to prove that ethics, aesthetics, and logic are alike in that they cannot be expressed by meaningful propositions. Wandering between the strictly logical and the mystical, Wittgenstein discusses topics that range from the picture-theory of proposition and logical atomism to truth-functionality, from the foundations of ontology and epistemology to the conception of the normativity of natural laws, from reflections on solipsism to ethics, aesthetics and theology. The logical Wittgenstein of the Tractatus particularly conditioned the emergence of the neo-positivist philosophy of the Vienna Circle, which was formed in the Austrian capital during the first post-war period and brought together thinkers such as Moritz Schlick (1882–1936), Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970), Otto Neurath (1882–1945) and Friedrich Waismann (1896–1959).

The period of the Philosophical Investigations coincides with an evolution in Wittgenstein’s consideration of language, which is now traced back to linguistic practices – the well-known “language games” – that reveal specific configurations of human behaviour – “forms of life”. These notions reveal an affinity with the “linguistic-pragmatic turn” in the philosophy of language, and are applied variously by the author in the philosophy of psychology, in anthropological reflections (see, for example, his Notes on Frazer’s “The Golden Bough”) and in his work on the foundations of mathematics.

The discontinuity between Wittgenstein's early thought and his mature reflections has often been emphasized – even by Wittgenstein himself, in some passages – especially with regards to the evolution of his conception of the nature of language: as formally structured in the “early” Wittgenstein, and as linked to the variable forms of culture in the “later” Wittgenstein. However, lines of continuity can be discerned, especially in the conception of philosophy as a “critique of language" and the “ethical point” of philosophical work, which is not intended to operate as a foundation nor give rise to a theory, but rather reflects the transformative force of the human being.

About Wittgenstein’s works and The Ludwig Wittgenstein Project’s policy

Wittgenstein wrote a lot but published little: a very short review of Peter Coffey’s The Science of Logic; the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus; a dictionary, or rather a spelling book, for German-speaking schoolchildren; an academic article by the title Some Remarks on Logical Form; a letter to the editor of Mind. Almost everything we now have in volume format was published posthumously. After Wittgenstein died in 1951, his appointed literary executors, G.E.M. Anscombe, R. Rhees and G.H. von Wright, were left with the task of sorting and grouping his handwritten notes and typescripts in order to publish them.

Now, the Nachlass itself – the collection of Wittgenstein’s manuscript material, the “raw” Wittgenstein – has been available online since the 2010s, almost in its entirety, both in a fac-simile edition and in an XML/HTML transcription. This was made possible by the generosity of the copyright holders of the originals, The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, and the work of the Wittgenstein Archives Bergen. Much of the digitalized content has been released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license.

A scan of Ms-102,14v (diary entry dated 13 November 1914). The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, The University of Bergen, Bergen, CC BY-NC.

Some parts of the Nachlass were carefully prepared for publication by Wittgenstein himself, and it is fair to assume that he would have had them printed had he lived longer. The Philosophical Investigations, for which he even wrote a preface in 1945, are the best example of a text thoroughly crafted by Wittgenstein and ready for the press by the time he passed away. In other cases, however, his notes were only published as books after undergoing extensive editing: this is the case, for example, with the lectures he held in Cambridge and the private conversations, that we have received through notes taken by his students and interlocutors. There are midway cases as well, texts such as On Certainty, Remarks on Colours, Zettel, Philosophical Grammar, Culture and Value. In order to prepare these texts for publication the editors selected, grouped, and sorted the remarks.

Based on our expertise in the field of copyright, we at The Ludwig Wittgenstein Project decided to only publish those texts for which we had strong reasons to determine that the editors' work can not be considered creative. The list of available texts meeting these criteria is constantly being updated.

Individual works (forthcoming)

This paragraph lists Wittgenstein’s writings that are available on this website and provides a very short introduction to their editorial history and philosophical content.

Review of P. Coffey, The science of logic Expand

“Don’t worry, I know you’ll never understand it”: with these words about the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein addressed Russell and Moore during the assessment meeting to obtain a Ph.D. at Cambridge, where Wittgenstein presented the book as his thesis. And indeed, since its appearance, the book aroused continuous and strong interest because of its enigmatic appeal no less than its undisputed brilliance. The work for which Wittgenstein is best known, the Tractatus is the only one published by the author during his lifetime. In spite of its size (75 pages in the first English edition), the book represents one of the greatest masterpieces of 20th century philosophy: in the 525 propositions arranged in a progressive numbering system, in which seven main propositions incorporate a variable number of commentary propositions hierarchically organised, Wittgenstein summarises his early philosophy, establishing a relationship between the themes of logic and language, newly developed by logicism between the 19th and 20th centuries, and the traditional spiritual problems of ethics and value, which lie at the intersection of philosophy and religion.

The genesis of the tractarian ideas can be attributed to the unique blend of influences absorbed by the author during the early phase of his intellectual production. Well before engaging with academic philosophy, Wittgenstein assimilated the contributions of, among others, Schopenhauer, Tolstoy, Hertz, polemical literature, and Jewish thought, which were prevalent in the intellectual discourse of fin de siècle Vienna. This culturally vibrant environment was deeply committed to envisioning a reform of communicative, ethical, and aesthetic codes that would provide the proper space for existential reflections. Upon his exposure to the philosophies of Frege and Russell, Wittgenstein adopted the conviction that symbolism, serving as a unifying instrument, could integrate his understanding of the interplay between language and the world with the belief that essential problems could not be subject to intellectual discourse.

The first attempts to organize the material he developed at Cambridge took place between 1913 and 1914, during a period of self-isolation in Skjolden (Norway), where Wittgenstein built himself a cabin in order to find the necessary solitude to write his first notes (which later evolved into the Notes on Logic and the Notes dictated to Moore). With the outbreak of the First World War, Ludwig voluntarily enlisted in the Austrian army. The decision to subject himself to the harsh trials of military life in pursuit of a heroic effort to perfect himself and find definitive solutions to logical and existential problems is undoubtedly a testament to the romantic and anguished nature of the Austrian genius, which is reflected in Wittgenstein's war diaries. These Notebooks (1914-1916) contain logical-philosophical observations along with more private and introspective annotations, many of which were preserved with little or no alteration in the book, following various processes of revision, selection, and organization, of which a key step was the composition of a "Prototractatus." The final version of the Tractatus was completed in 1918, but difficulties arose in finding a publisher willing to print a work of such modest size and due to Wittgenstein's stubborness (he insisted on not publishing the book at his own expense, considering it an affront to what he regarded as the work of his life), which delayed its publication until 1922. Prior to this, a German edition had been released in 1921 in the journal Annalen der Naturphilosophie under the title of Logisch-Philosphische Abhandlung, but Wittgenstein repudiated it as a "pirated edition" because of alterations made during the printing process. Therefore, the only edition he considered correct was the English one, whose iconic title was suggested by G. E. Moore and which was published in London by Kegan Paul with a translation by F. P. Ramsey and C. K. Ogden, reviewed and approved by Wittgenstein. It was accompanied by an Introduction written by Russell, of which the author himself was never truly satisfied.

Despite their remarkable depth, the fundamental ideas of the Tractatus can be summarized in relatively few lines. "The world is everything that is the case" (1) is the proposition that opens the first part of the book, dedicated to the relationship between reality and language. Wittgenstein essentially suggests that all meaningful propositions speak of "atomic facts" (2), which are possible situations arising from the interaction of objects. Language reproduces these connections by designating each object with a simple sign, and a propositional sign is a "picture of reality" (4.01) formed by combining these simple signs. The possibility of representation that links the world, thought, and linguistic expression reveals the presence of structural relationships among these entities, which Wittgenstein qualifies as "logical form, that is, the form of reality" (2.18). This “picture-theory”, as it has been renamed, leads to the idea that logic is the common foundation of the world and language, upon which every statement is connected to the state of affairs it represents. However, the symbolic expression that transforms pure representational logical connections into communications within every-day language often generates distortions of the representational projection, which constitute "the most fundamental confusions (of which the whole philosophy is full)" (3.324). In other words, "language disguises the thought" (4.002).

The purpose of philosophy, which Wittgenstein qualifies as the "activity" of "logical clarifiation of thoughts" (4.112), is thus the dissolution of philosophical problems themselves through the simple elucidation of the "logic of language" (4.002). Adhering to the logicist program, Wittgenstein expresses in the book the belief that this activity can be better conducted through the analysis (that is, the examination and reduction into further indivisible signs, 2.0201) of propositions that give rise to misunderstandings, ultimately aiming at developing an ideal logical ideography (which he himself employed in a form he developed), that renders errors and misinterpretations impossible. While it is evident that Wittgenstein adopts a rational approach, he maintains that philosophy cannot be regarded on par with science. Instead, "all philosophy”, he writes, “is ‘Critique of language’" (4.0031), highlighting the focus on examining and clarifying the language used in philosophical discourse rather than constructing a separate body of knowledge akin to scientific theories.

What is illustrated by Wittgenstein here follows what he anticipates in the Preface of the book when he asserts that "what can be said at all can be said clearly": philosophy delimits the thinkable and, therefore, the speakable by circumscribing meaningful combinations of signs within language and drawing a limit between everything that can be meaningfully expressed and what is mere nonsense. Since language and the world have symmetrical formal relationships, "the limits of my language mean the limits of my world" (5.6), a famous aphorism with which the author introduces a series of brief and striking reflections on the theme of solipsism and the "metaphysical subject" (5.633), expressing skepticism towards any form of sound philosophical discussion about the self. In fact, Wittgenstein adds, the peculiarity of the philosophical endeavor is that the limit of language (and hence of the world) is itself not susceptible to a meaningful linguistic representation because "propositions […] cannot represent what they must have in common with reality in order to be able to represent it—the logical form" (4.12).

Not only propositions that deal with the logic of language but also any proposition formulated with the intent of expressing something supernatural ultimately turns out to be nonsensical. Essentially, this applies to every proposition that, in contrast to the laws of assertion, does not aim to represent a state of affairs but rather to formulate a value judgment about the world, beacuse "the sense of the world must lie outside of the world" (6.41), that is, outside of the realm of what is linguistically representable. Therefore, at the end of the book, in a series of deliberately aphoristic and emotionally powerful statements, Wittgenstein argues that propositions of ethics, aesthetics, and religion are equally nonsensical ("it is clear that ethics cannot be expressed", 6.421). What this kind of propositions would like to convey, interpreting the human instinct to go beyond the limits of language, belongs to the realm of the “inexpressible”, which "shows itself" and which Wittgenstein designates as "the mystical" (6.522). The crucial distinction between "saying" and "showing" is introduced by Wittgenstein to illustrate that "what can be shown cannot be expressed" (4.1212) by means of language, thus acknowledging a certain allusive power in his elucidatory propositions too, that are capable of conveying inherently incommunicable ideas ("he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them", 6.54). Nevertheless, he reiterates in concluding the book that the "only strictly correct method" (6.53) of philosophy as a practice of clarification is to abstain from any "metaphysical" discourse, inviting therefore to recognize the nonsensical nature of tractarian propositions, to "surmont" them, and to rid oneself of them, throwing away the ladder after climbing up on it (6.54). Once the right view of the world and language that the Tractatus proposes is attained, the only task remaining is to give concreteness to its theses and to refrain from any nonsensical philosophical discourse: "whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent" (7).

The assertive tone and the lack of further explanatory propositions after the well-known final statement of the Tractatus betray Wittgenstein's confidence in having "essentially solved the problems" (Preface). In his view, the book offered a definitive solution to philosophical problems of language, value, and existence, and both areas (logic and ethics) held equal importance as they carried the same significance for the author. The sense of the book, as stated in a letter sent by Wittgenstein to the publisher Ludwig von Ficker, is an ethical sense: "my work consists of two parts: of the one which is here, and of everything which I have not written. And precisely this second part is the important one. For the Ethical is delimited from within, as it were, by my book [...] In brief, I think: All of that which many are babbling today, I have defined in my book by remaining silent about it". Indeed, it is a rather paradoxical result that the thoughts which fill the book, despite their "unassailable and definitive" truth (Preface), are, strictly speaking, incommunicable! The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus presents a unique challenge in that it grapples with the limits of language and the boundaries of meaningful communication on “what is higher” (6.432). Wittgenstein must have been aware of this when, sanctioning the proverbial futility of philosophy, he wrote in the Preface that "the value of the work lies [...] in showing how little it matters for these problems to be solved".

Considering all this, it is at least reductive to narrow down the legacy of the book to its influence on the development of neologicist philosophy, as is often still done today. It is true that the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus contains the fundamental theoretical elements (from logical atomism to truth-functionality to the verification principle) that were later elaborated by the Vienna Circle (although Wittgenstein began to suspect that some of his statements lent themselves to misunderstandings precisely because of the neo-positivist interpretation offered by the Circle). However, the book shows several connections with the rationalist and romantic German philosophy of the time and, thanks to the ease with which the author moves between logic and epistemology, ontology and ethics, it constitutes an irreplaceable document not only as a basis to access Wittgenstein's thought and his later production but also, more generally, for understanding the intellectual culture of Europe in the 20th century, which remained deeply fascinated by this philosophical masterpiece.

Go to Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

In the only footnote of the book, Wittgenstein himself provided instructions for understanding the numerical hierarchy underlying the lines of reasoning presented in the Tractatus. Each of the main propositions is accompanied by sequentially numbered comment propositions with a single decimal place; in turn, these incorporate comment propositions with two decimal places, and so on. Nowadays, thanks to modern computer techniques, many digital tools have multiplied to reproduce the tree-like structure at the base of the book in the form of a diagram (as in the case of the University of Iowa Tractatus map) or through collapsible "drawers" that allow hiding or showing the commentary subpropositions. The Ludwig Wittgenstein Project has developed its own version of the tree-like view of the Tractatus to offer users a reading experience as closely aligned as possible with Wittgenstein's indications. Go to Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (tree-like view)

Furthermore, with the aim of facilitating the comparison between original editions and translations of the work, we have developed a multilingual interface that allows side-by-side display of the original texts and the translations which are currently available on the website. Go to the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (side-by-side view)

Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough Expand

"Philosophical Investigations" is the title that Wittgenstein, starting from the mid-1930s, attributed to a collection of German-language manuscripts, often converted into typescripts, which he repeatedly, extensively, and compulsively revised in an attempt to shape his second book of philosophy. Even if the resulting typescript (Ts-227 in von Wright's catalogue) is considered to be the most polished among the later Wittgenstein's writings, the book did not see the light of day during the author's lifetime: it was only in 1953 that Wittgenstein's literary executors posthumously published the text along with G.E.M. Anscombe’s English translation, in a form that has not failed to provoke criticism due to the inclusion of a so-called “Part II” of the work. The content of this section consists of materials written between 1947 and 1949, which Wittgenstein made a selection of and had typed out (the resulting typescript was catalogued as Ts-234). G.E.M. Anscombe and Rush Rhees claimed that it was his intention to incorporate these contents into the final version of the work, but they also made it clear that it was their decision to attach "Part II", in its relatively "raw" form, to the relatively "finished" text of "Part I". Additionally, the themes discussed in "Part II" are more closely related to the work Wittgenstein carried out on the philosophy of psychology after 1945. For these reasons, on our website, we exclusively reproduce what is known as "Part I" of the work, as do an increasing number of recent editions of the Philosophical Investications – for example, Joachim Schulte's German edition. Schulte also observes that the integration proposed by the literary executors, while it was welcome at the time of publication as it allowed the reader of the Investigations to become acquainted with reflections by Wittgenstein that would otherwise have remained unknown for many years, is now superfluous, because the content of "Part II" is now widely available thanks to the electronic editions of the Nachlass.

Although the final version of the first part of the work was only composed between 1943 and 1945, with some marginal rehashes thereafter, it would be flawed to argue that the Investigations reflect a phase of Wittgenstein's thought whose scope is limited to the early 1940s. As he writes in the Preface, the ideas contained in the book are "the precipitate of philosophical investigations which have occupied me for the last sixteen years". Therefore, the Philosophical Investigations can be considered a synthesis of Wittgenstein's mature thought, following his return to philosophy in 1929. Once again, the result of years of gestation was a complex work, devoid of a hierarchical structure and a definitive status unlike the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, but equally rich and surprising.

In the 693 numbered paragraphs of the first part of the work, which follow slender and rarely explicit logical threads, Wittgenstein addresses many subjects, as summarized in the Preface: “the concepts of meaning, of understanding, of a proposition and sentence, of logic, the foundations of mathematics, states of consciousness, and other things”, without, however, providing a systematic treatment of them, but rather free remarks or, as the author puts it, “a number of sketches of landscapes which were made in the course of those long and meandering journeys”. This method corresponds to a renewed conception of the nature of the philosophical enterprise, which Wittgenstein presents in paragraphs 109-133: as he had already argued in the Tractatus, the aim is to solve philosophical pseudo-problems by dissolving the confusions that arise in the everyday use of language. However, for the author of the Investigations, this activity of clarification no longer involves a refinement of the linguistic code according to ideal, logical criteria. “Every sentence in our [ordinary] language is in order as it is” (§ 98): these kind of observations convey the idea that the principles that define the meaningfulness of language reside within language itself, and its intelligibility does not derive from compliance with logical rules, but rather from "grammatical" rules, that is, from the overall evaluation of the diverse uses of signs. Consequently, the philosopher's task does not consist in providing explanations about the nature of language, but rather in offering descriptions of language use, thus elucidating the inconspicuous implications of the linguistic activity that are not immediately recognizable.

Throughout the work, therefore, Wittgenstein establishes some cornerstones of his new thought, such as the idea that “the meaning of a word is its use in the language” (§ 43): in order to know the meaning of a sign, one must observe the situations in which that sign is used, evaluate the ways in which its usage is taught, and the customary practices by which that usage is transmitted, preserved, or transformed. Hence, Wittgenstein's constant tendency to put on scenes of instruction or plausible episodes from the lives of less civilised people, to demonstrate that even the most basic form of complex linguistic-conceptual constructions, such as mathematics or abstract reasoning, is not a system of propositions based on logical laws, but a set of elementary practices, whose rules are mastered by the owners of a given language through training.

The inclination to disappoint the rationalist perspectives with a heuristic approach to language and to present several “language games” as “objects of comparison” (§ 130) for examining the meaning of problematic expressions represents both a critique of classical theories of language, built upon the concepts of "representation", "proposition", and "logical atomism" (including those presented in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus), and a renewal of the research method. Language, according to Wittgenstein, plays a role only when it is engaged in specific activities. With language, we do all sorts of things: that is why every language has sense within a specific "form of life", which is the set of contexts and circumstances that contribute to determining meanings, and the famous expression “language-game” is precisely intended “to emphasize the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or a form of life” (§ 23).

The themes explored by Wittgenstein are too numerous and disparate to be briefly summarized. He focuses on the ostensive learning of language, challenging the ideas attributed to Augustine; he discusses the concepts of "rule" and "understanding"; he introduces the notion of "family resemblances" (§ 67) to draw attention to the similarities and differences of the use of the same sign in different contexts; he raises questions on the relationship between word and thought and the plausibility of a "private language" in a series of famous reasonings that include the example of the "beetle in the box" (from which the logo of our project is derived, § 293). But, essentially, in both the first and second parts of the work, Wittgenstein unceasingly applies the principles of his new philosophical method: by presenting several examples, thought experiments, imaginary situations, and comparisons, he examines the “misunderstandings concerning the use of words […] in different regions of our language” (§ 90) and encourages the reader to adopt a more cautious and contextual approach to understanding language, ultimately arguing that what we call “philosophical problems” are merely confusions, which are only dispelled by achieving a “perspicuous representation” (§ 122) of our ordinary language.

The style of the Philosophical Investigations is often aphoristic and fragmented. Wittgenstein repeatedly expressed his dissatisfaction with the form he was able to give to the book, as he recalls at the end of the Preface. It is not surprising that many passages have generated lively interpretative debates and continue to do so. Its nature as an open work, the hypnotic structure of the argumentation, and the innovative variety of themes and methodology make it a milestone in recent philosophy, at least on par with the Tractatus Logico-philosophicus, as demonstrated by the massive influence this text had on the development of the so-called "ordinary language philosophy" and on Western thought as a whole in the second half of the 20th century.